Week 2: Building App UI¶

Kotlin fundamentals¶

Conditionals¶

ifstatements:if (condition1) { // code to execute if condition1 is true } else if (condition2) { // code to execute if condition2 is false } else if (condition3) { // code to execute if condition3 is false } else { // code to execute if condition is false }

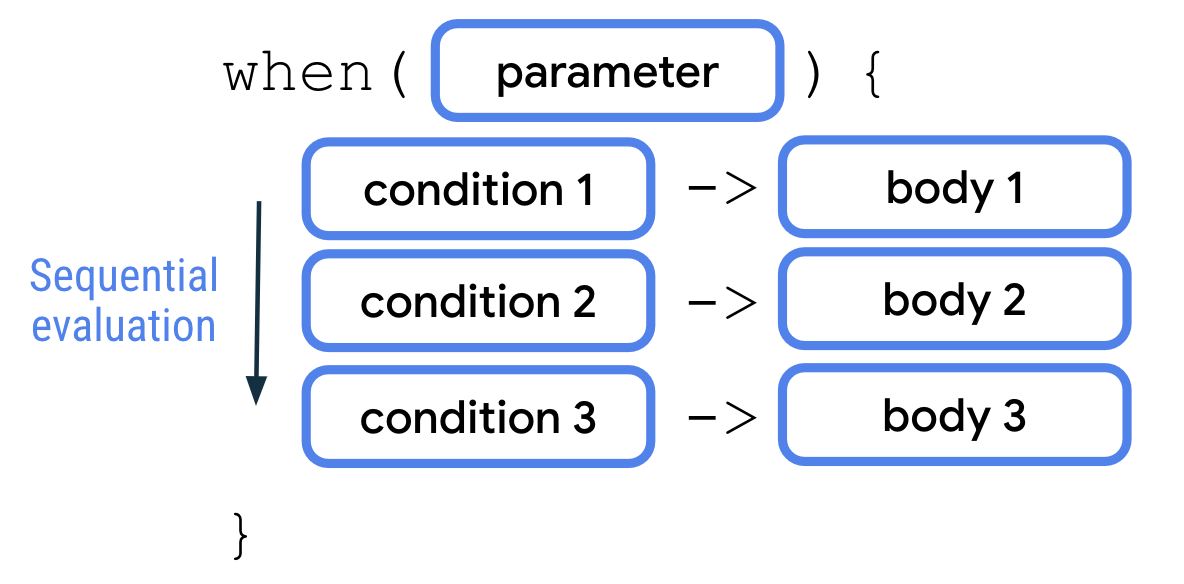

When there are more than 2 branches, use the

whenstatement.

Examples:

fun main() { val trafficLightColor = "Black" when (trafficLightColor) { "Red" -> println("Stop") "Yellow" -> println("Slow") "Green" -> println("Go") else -> println("Invalid traffic-light color") } }

fun main() { val x = 3 when (x) { 2 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") 3 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") 5 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") 7 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") else -> println("x isn't a prime number between 1 and 10.") } }

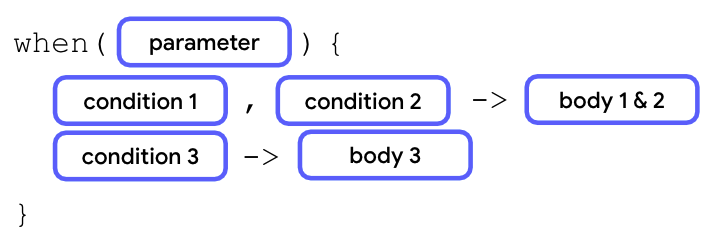

Use

,to denote multiple conditions:

Example:

fun main() { val x = 3 when (x) { 2, 3, 5, 7 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") else -> println("x isn't a prime number between 1 and 10.") } }

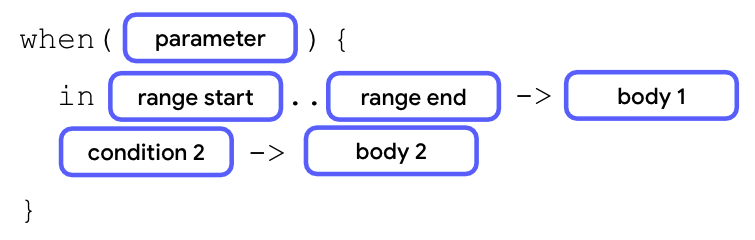

Use the

inkeyword and a range of values:

fun main() { val x = 3 when (x) { 2, 3, 5, 7 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") in 1..10 -> println("x is a number between 1 and 10, but not a prime number.") else -> println("x isn't a prime number between 1 and 10.") } }

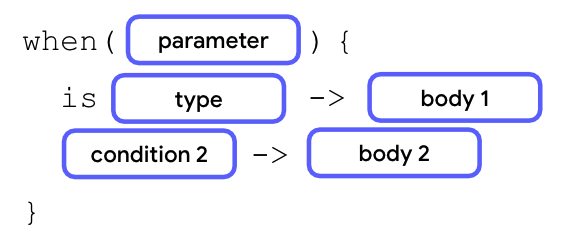

Use the

iskeyword to check the data type:

fun main() { val x: Any = 20 when (x) { 2, 3, 5, 7 -> println("x is a prime number between 1 and 10.") in 1..10 -> println("x is a number between 1 and 10, but not a prime number.") is Int -> println("x is an integer number, but not between 1 and 10.") else -> println("x isn't an integer number.") } }

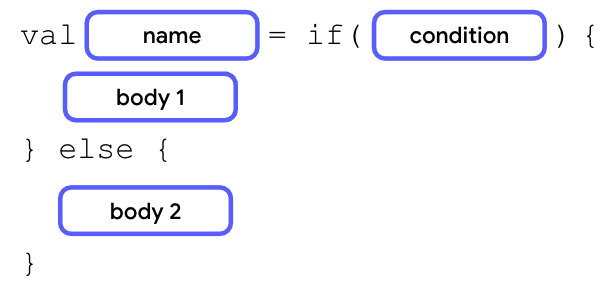

You can also use conditionals as expressions to return different values for each branch of condition:

If the bodies only contain a return value or expression, you can remove the curly braces to make the code more concise.

Examples:

fun main() { val trafficLightColor = "Black" val message = if (trafficLightColor == "Red") "Stop" else if (trafficLightColor == "Yellow") "Slow" else if (trafficLightColor == "Green") "Go" else "Invalid traffic-light color" println(message) }

fun main() { val trafficLightColor = "Amber" val message = when(trafficLightColor) { "Red" -> "Stop" "Yellow", "Amber" -> "Slow" "Green" -> "Go" else -> "Invalid traffic-light color" } println(message) }

In most cases, a

whenexpression requires theelsebranch because thewhenexpression needs to return a value. The Kotlin compiler checks whether all the branches are exhaustive. Anelsebranch ensures that there won’t be a scenario in which the variable doesn’t get assigned a value.

Nullability¶

Use

nullto indicate that there’s no value associated with a certain variable. Example:fun main() { val favoriteActor = null }

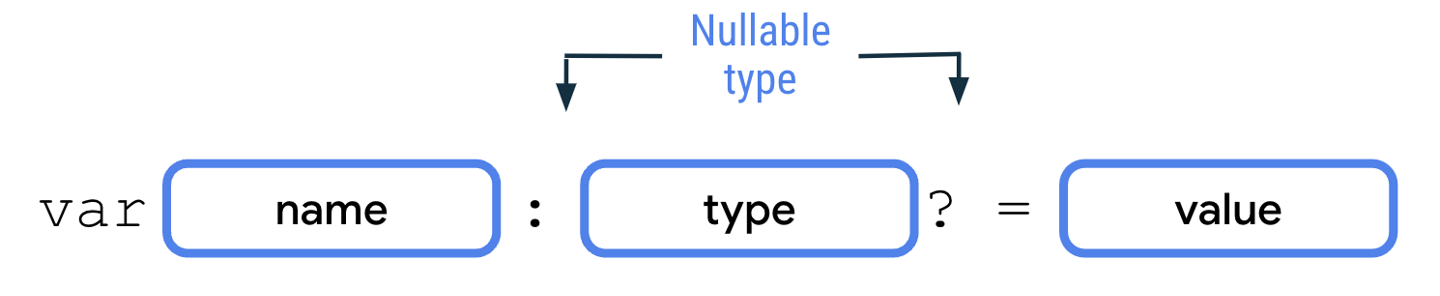

Nullable vs non-nullable types:

Nullable types are variables that can hold

null.Non-nullable types are variables that cannot hold

null.

For example, a

String?type can hold either a string ornull, whereas aStringtype can only hold a string. To declare a nullable variable, you need to explicitly add the nullable type. Without the nullable type, the Kotlin compiler infers that it’s a non-nullable type.fun main() { var number: Int? = 10 println(number) number = null println(number) }

Note

While you should use nullable variables for variables that can carry

null, you should use non-nullable variables for variables that can never carrynullbecause the access of nullable variables requires more complex handling.The code below produces an error message:

fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = "Sandra Solulu" println(favoriteActor.length) }

This error is a compile error, or compile-time error. A compile error happens when Kotlin isn’t able to compile the code due to a syntax error in your code.

Kotlin achieves

nullsafety, which refers to a guarantee that no accidental calls are made on potentiallynullvariables. This doesn’t mean that variables can’t benull. It means that if a member of a variable is accessed, the variable itself can’t benull.This is critical because if there’s an attempt to access a member of a variable that’s

null- known as anullreference - the app crashes. This type of crash is known as a runtime error, in which the error happens after the code has been compiled, and runs.Due to

nullsafety, such runtime errors are prevented because the Kotlin compiler forces anullcheck for nullable types. Anullcheck refers to a process of checking whether a variable could benull, before it’s accessed and treated as a non-nullable type.There are various operators used to work with nullable variables.

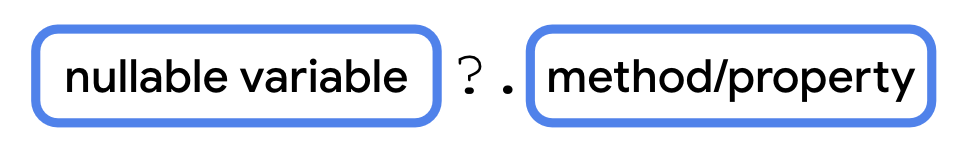

The

?.safe call operator is used to access methods or properties of nullable variables.

The

?.safe call operator allows safer access to nullable variables because the Kotlin compiler stops any attempt of member access tonullreferences and returnsnullfor the member accessed. Example:println(favoriteActor?.length)

When the below code is run, the output is

null. The program doesn’t crash despite an attempt to access thelengthproperty of anullvariable. The safe call expression simply returnsnull.fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = null println(favoriteActor?.length) }

Note

You can also use the

?.safe call operators on non-nullable variables to access a method or property. While the Kotlin compiler won’t give any error for this, it’s unnecessary because the access of methods or properties for non-nullable variables is always safe.The

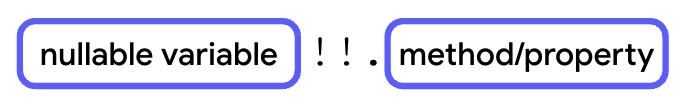

!!not-null assertion operator is used to access methods or properties of nullable variables.

If you use the

!!not-null assertion, it means that you assert that the value of the variable isn’t null, regardless of whether it is or isn’t. You’re telling the compiler, I’m very very very sure that this value isn’t null, don’t complain about it during compile time.Unlike

?.safe-call operators, the use of a!!not-null assertion operator may result in aNullPointerExceptionerror being thrown if the nullable variable is indeednull. Thus, it should be done only when the variable is always non-nullable or proper exception handling is set in place.Example:

fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = "Sandra Solulu" println(favoriteActor!!.length) }

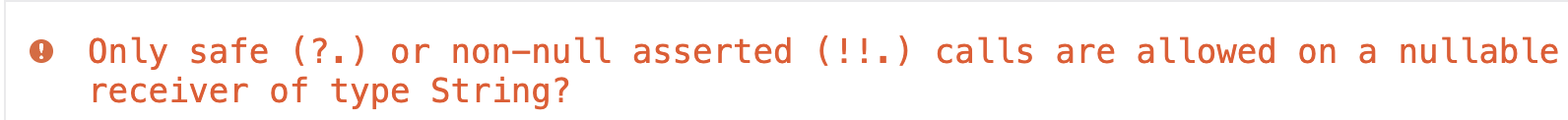

In the above code, if the

!!is removed, the compiler complains:Only safe (?.) or non-null asserted (!!.) calls are allowed on a nullable receiver of type 'kotlin.String?'.

By adding

!!, you’re telling the compiler that the value will never be null, and the compiler won’t complain during compile-time. However, if you were wrong and the value is indeed null, aNullPointerExceptionerror is thrown during run-time.Example of code that will not cause any compile-time error, but will cause a

NullPointerExceptionrun-time error:fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = null println(favoriteActor!!.length) }

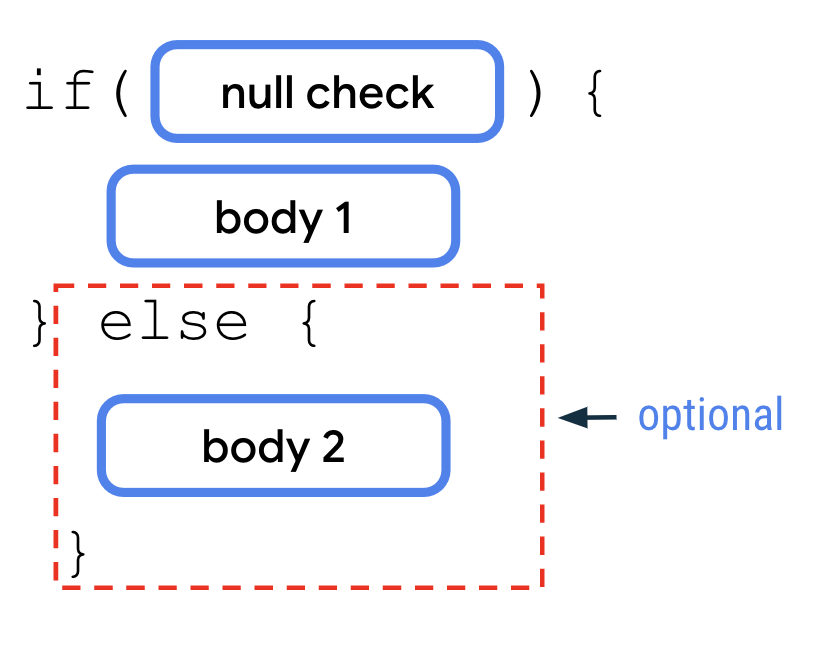

To perform

nullchecks, you can check that the nullable variable isn’t equal tonullwith the!=comparison operator

You can also check if a variable is null using

==To use

if/elsetogether with anullcheck:

The

nullcheck andifcondition are suitable when there are multiple lines of code that use the nullable variable. Example:fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = "Sandra Solulu" if (favoriteActor != null) { println("Your favorite actor's name is ${favoriteActor}.") println("The number of characters in your favorite actor's name is ${favoriteActor.length}.") } else { println("You didn't input a name.") } }

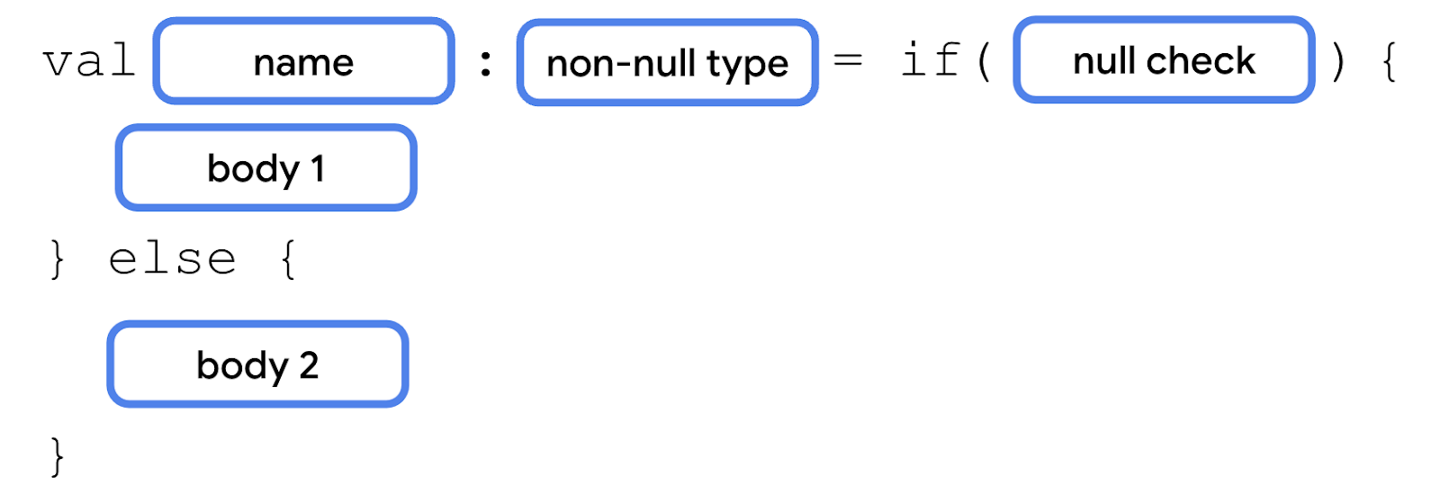

The

nullcheck andif/elseare suitable to convert a nullable variable to a non-nullable variable.

Example:

fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = "Sandra Solulu" val lengthOfName = if (favoriteActor != null) { favoriteActor.length } else { 0 } println("The number of characters in your favorite actor's name is $lengthOfName.") }

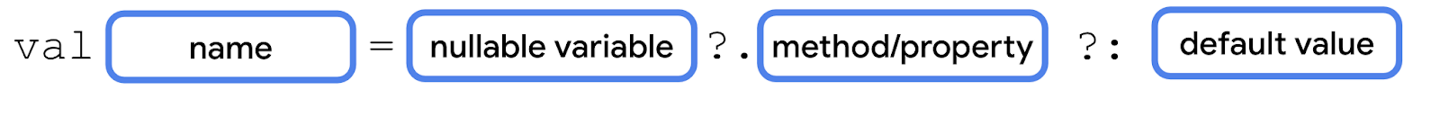

The

?:Elvis operator can be used together with the?.safe-call operator. It adds a default value when the?.safe-call operator returnsnull.

If the variable isn’t

null, the expression before the?:Elvis operator executes. If the variable isnull, the expression after the?:Elvis operator executes.Example:

fun main() { var favoriteActor: String? = "Sandra Solulu" val lengthOfName = favoriteActor?.length ?: 0 println("The number of characters in your favorite actor's name is $lengthOfName.") }

Classes and Objects¶

Classes provide blueprints from which objects can be constructed. An object is an instance of a class that consists of data specific to that object. The terms object and class instance are interchangable.

As an analogy, imagine that you build a house. A class is similar to an architect’s design plan, also known as a blueprint. The blueprint isn’t the house; it’s the instruction for how to build the house. The house is the actual thing, or object, which is built based on the blueprint.

Just like the house blueprint specifies multiple rooms and each room has its own design and purpose, each class has its own design and purpose. To know how to design your classes, you need to get familiar with object-oriented programming (OOP), a framework that teaches you to enclose data, logic, and behavior in objects.

OOP helps you simplify complex, real-world problems into smaller objects. There are four basic concepts of OOP:

Encapsulation. Wraps related properties, and methods that perform actions on those properties, in a class. For example, a phone encapsulates a camera, display, memory cards, and several other hardware and software components. You don’t have to worry about how components are wired internally.

Abstraction. An extension to encapsulation. The idea is to hide the internal implementation logic as much as possible. For example, to take a photo with your mobile phone, all you need to do is open the camera app, point your phone to the scene that you want to capture, and click a button to capture the photo. You don’t need to know how the camera app is built or how the camera hardware on your mobile phone actually works. In short, the internal mechanics of the camera app and how a mobile camera captures the photos are abstracted to let you perform the tasks that matter.

Inheritance. Enables you to build a class upon the characteristics and behavior of other classes by establishing a parent-child relationship. For example, there are different manufacturers who produce a variety of mobile devices that run Android OS, but the UI for each of the devices is different. In other words, the manufacturers inherit the Android OS feature and build their customizations on top of it.

Polymorphism. The word is an adaptation of the Greek root poly-, which means many, and -morphism, which means forms. Polymorphism is the ability to use different objects in a single, common way. For example, when you connect a Bluetooth speaker to your mobile phone, the phone only needs to know that there’s a device that can play audio over Bluetooth. However, there are a variety of Bluetooth speakers that you can choose from and your phone doesn’t need to know how to work with each of them specifically.

Smart Home App¶

To learn about classes and objects, we’ll build a smart home app that simulates the behavior of smart devices. The app consists of a class structure that represents smart devices, such as a smart TV and a smart light.

The code that we write won’t interact with real hardware devices. Instead, we’ll print actions in the console using

println()to simulate the interactions.

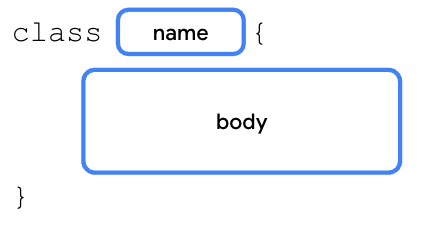

Define a class¶

When you define a class, you specify the properties and methods that all objects of that class should have.

To define a class:

The part before the opening curly brace is known as the class header.

Class naming conventions:

Don’t use Kotlin keywords (like

fun, etc) as a class nameUse PascalCase: each word begins with a capital letter, no spaces.

A class consists of three major parts:

Properties: variables that specify the attributes of the class’s objects.

Methods: functions that contain the class’s behaviors and actions.

Constructors: a special function that creates instances of the class throughout the program in which it’s defined.

Data types like

Int,Float,String, andDoubleare classes. For example, this code creates an object of theIntclass:val number: Int = 1

Example of a bare basic class:

class SmartDevice { // empty body } fun main() { }

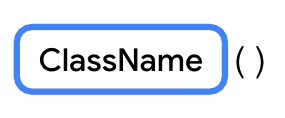

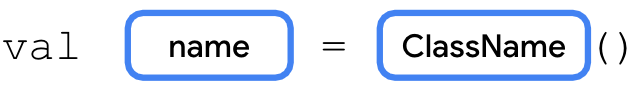

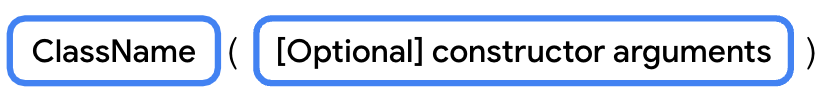

Create a class instance¶

A class is a blueprint for an object. The Kotlin runtime uses the class to create an object of that particular type. The

SmartDeviceclass is a blueprint of what a smart device is. To have an actual smart device in your program, you need to create aSmartDeviceobject instance. Creating an object instance is known as instantiation.The instantiation syntax:

To create the object and assign it to a variable:

When using the

valkeyword, the variable is immutable, but the object itself is mutable. This means that you can’t reassign another object to the variable, but you can change the object itself.Example:

val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() // Cannot smartTvDevice = AnotherSmartDevice() // Can smartTvDevice.someProperty = "some value"

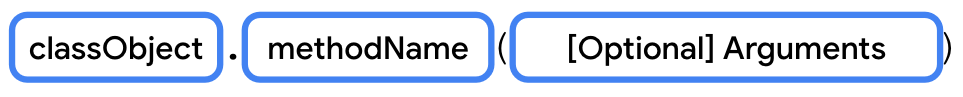

Define class methods¶

Class methods are actions that the class can perform. They are defined as functions in the class. For example, imagine that you own a smart device, a smart TV, or a smart light, which you can switch on and off with your mobile phone. The smart device is translated to the

SmartDeviceclass in programming, and the action to switch it on and off is represented by theturnOn()andturnOff()functions, which enable the on and off behavior.To define a function in a class, place the function in the class body. A function inside a class body is known as a member function or a method.

Example:

class SmartDevice { fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } }

So far, you defined a class that serves as a blueprint for a smart device, created an instance of the class, and assigned the instance to a variable. Now you use the

SmartDeviceclass’s methods to turn the device on and off.To call a class method from outside of the class:

Example:

fun main() { val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() smartTvDevice.turnOn() smartTvDevice.turnOff() }

Define class properties¶

Class methods define the actions that a class can perform. Class properties define the class’s characteristics or data attributes. For example, a smart device has these properties:

Name: name of the device.

Category: type of the device, such as entertainment, utility, or cooking.

Device status: whether is is on, off, online, or offline. The device is considered online when it’s connected to the internet. Otherwise, it’s considered offline.

Class properties are defined in the class body. Example:

class SmartDevice { val name = "Android TV" val category = "Entertainment" var deviceStatus = "online" fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } } fun main() { val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() println("Device name is: ${smartTvDevice.name}") smartTvDevice.turnOn() smartTvDevice.turnOff() }

Properties can do more than a variable can. For example, imagine that you create a class structure to represent a smart TV. One of the common actions that you perform is increase and decrease the volume. To represent this action in programming, you can create a property named

speakerVolume, which holds the current volume level set on the TV speaker, but there’s a range in which the value for volume resides. The minimum volume one can set is 0, while the maximum is 100.To ensure that the

speakerVolumeproperty never exceeds 100 or falls below 0, you can write a setter function. When you update the value of the property, you need to check whether the value is in the range of 0 to 100.As another example, imagine that there’s a requirement to ensure that the name is always in uppercase. You can implement a getter function to convert the

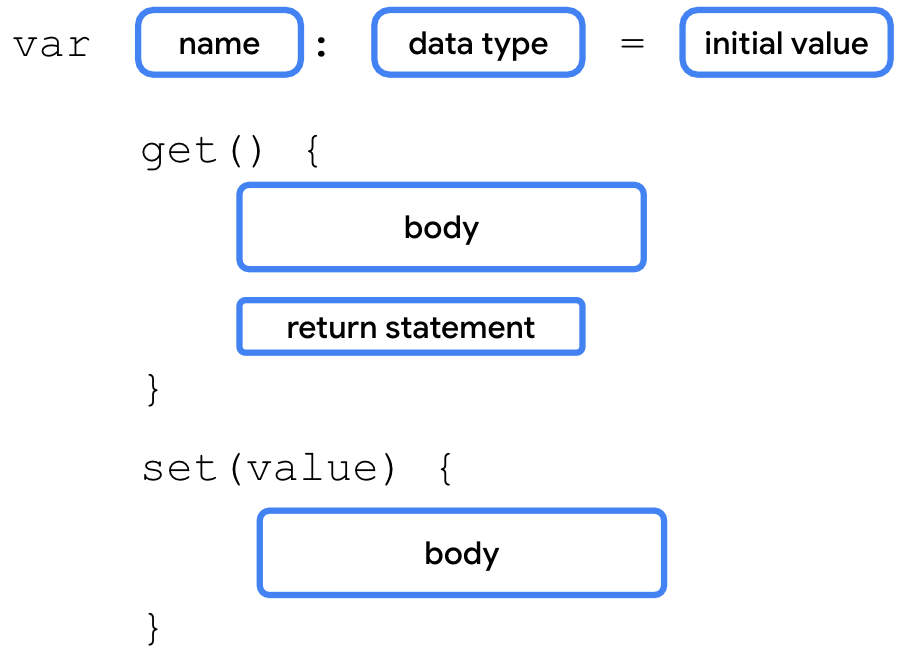

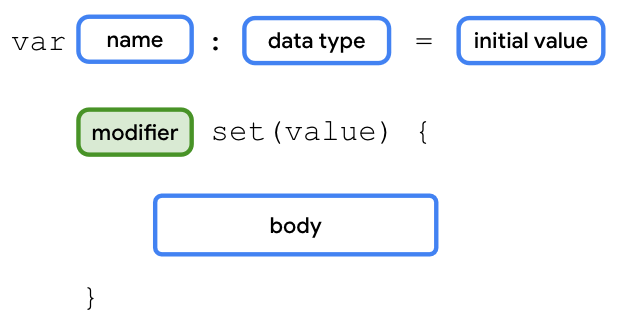

nameproperty to uppercase.Full syntax to define a mutable property:

When you don’t define the getter and setter function for a property, the Kotlin compiler internally creates the functions. For example, if you use the

varkeyword to define aspeakerVolumeproperty and assign it a2value, the compiler autogenerates the getter and setter functions as you can see in this code snippet:

var speakerVolume = 2

get() = field

set(value) {

field = value

}

You won’t see these lines in your code because they’re added by the compiler in the background.

The full syntax for an immutable property has two differences:

It starts with the

valkeyword.The variables of

valtype are read-only variables, so they don’t haveset()functions.

Properties use a backing field to hold a value in memory. A backing field is basically a class variable defined internally. A backing field is scoped to a property, which means that you can only access it through the

get()orset()property functions.To read the property value in the

get()function or update the value in theset()function, you need to use the property’s backing field. It’s autogenerated by the Kotlin compiler and referenced with afieldidentifier.Example: to update the property’s value in the

set()function:var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { field = value }

Warning

Don’t use the property name to get or set a value. For example, in the

set()function, if you try to assign the value parameter to thespeakerVolumeproperty itself, the code enters an endless loop because the Kotlin runtime tries to update the value for thespeakerVolumeproperty, which triggers a call to the setter function repeatedly.Example: to ensure that the value assigned to the

speakerVolumeproperty is in the range of 0 to 100:var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } }

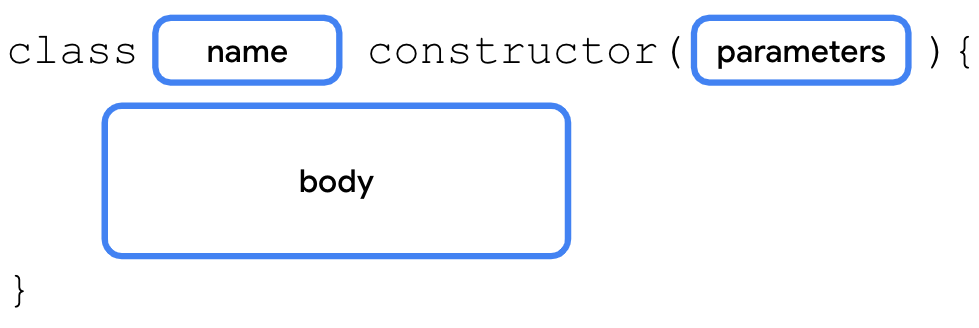

Define a constructor¶

A constructor specifies how the objects of the class are created. Constructors initialize an object, and make the object ready for use. The code inside the constructor executes when the object of the class is instantiated. You can define a constructor with or without parameters.

A default constructor is a constructor without parameters:

class SmartDevice constructor() { ... }

Kotlin aims to be concise, so you can remove the

constructorkeyword if there are no annotations or visibility modifiers (more on this later), on the constructor.class SmartDevice() { ... }

You can also remove the parentheses if the constructor has no parameters:

class SmartDevice { ... }

The Kotlin compiler autogenerates the default constructor. You won’t see the autogenerated default constructor in your code because it’s added by the compiler in the background.

A parameterized constructor is a constructor that accepts parameters.

In the

SmartDeviceclass, thenameandcategoryproperties are immutable. To maintain immutability but avoid hardcoded values, use a parameterized constructor to initialize them:class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } }

The constructor now accepts parameters to set up its properties. The full syntax to instantiate an object using a parameterized constructor:

Note

If the class doesn’t have a default constructor and you attempt to instantiate the object without arguments, the compiler reports an error.

Example:

SmartDevice("Android TV", "Entertainment")

Both arguments to the constructor are strings. It’s a bit unclear as to which parameter the value should be assigned. To fix this, you can create a constructor with named arguments:

SmartDevice(name = "Android TV", category = "Entertainment")

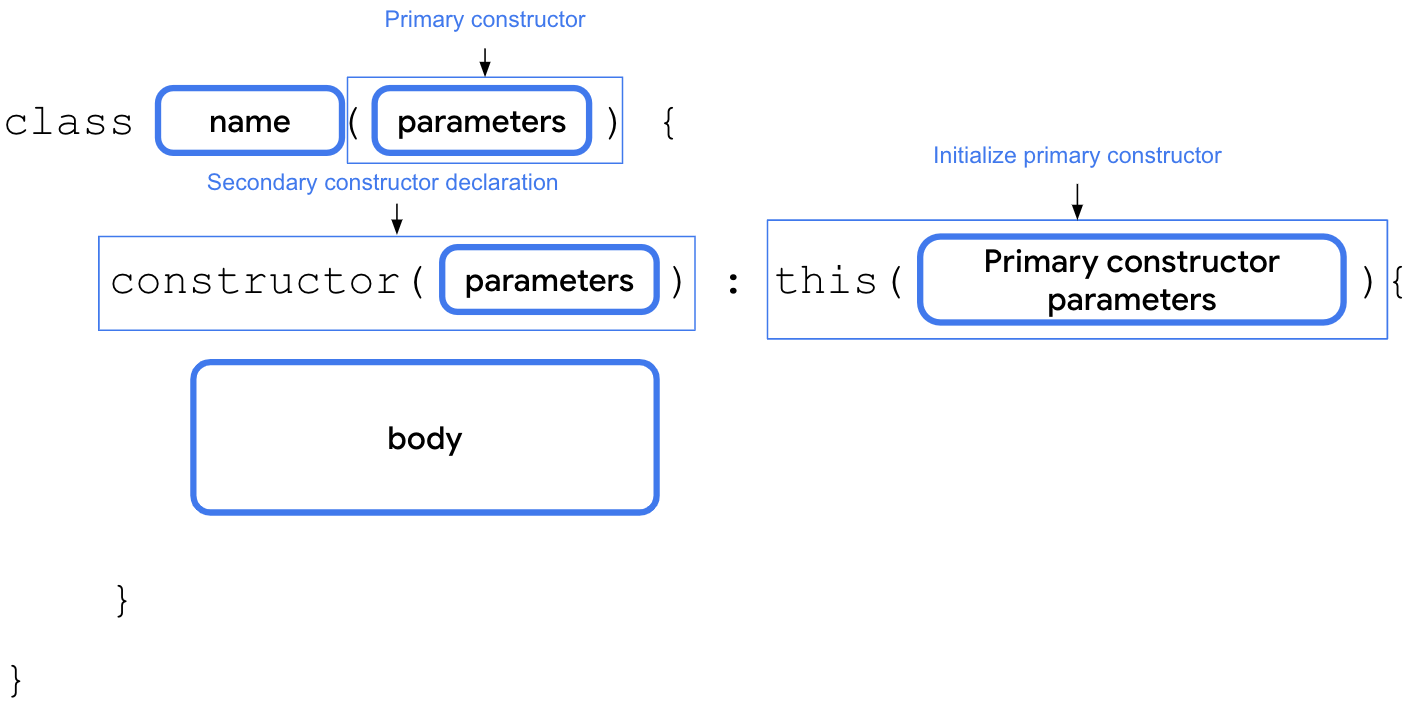

There are two main types of constructors in Kotlin:

Primary constructor. A class can have only one primary constructor, which is defined as part of the class header. A primary constructor can be a default or parameterized constructor. The primary constructor doesn’t have a body. That means that it can’t contain any code.

Secondary constructor. A class can have multiple secondary constructors. You can define the secondary constructor with or without parameters. The secondary constructor can initialize the class and has a body, which can contain initialization code. If the class has a primary constructor, each secondary constructor needs to initialize the primary constructor.

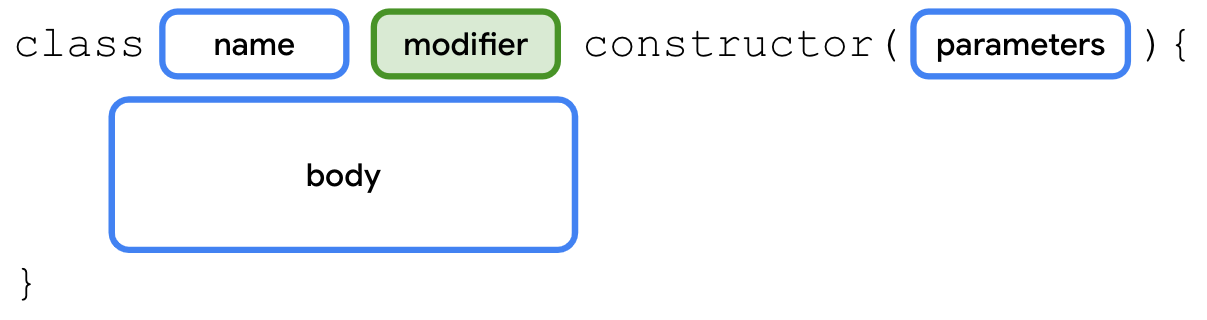

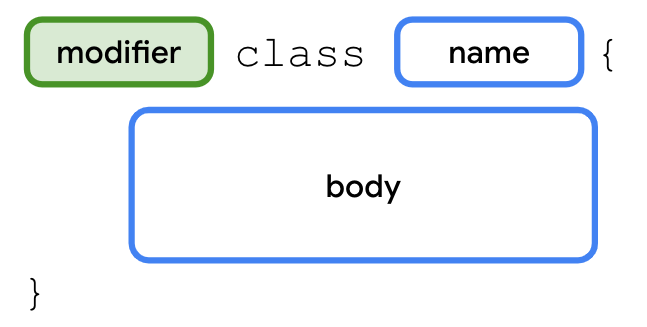

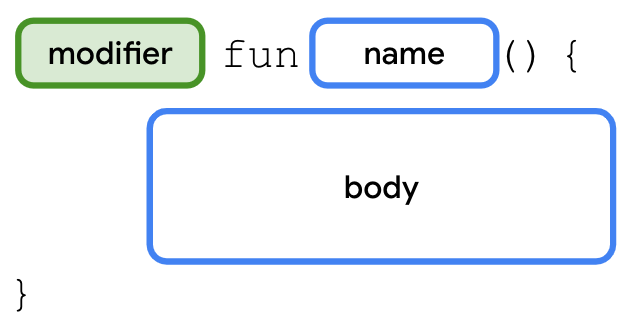

You can use the primary constructor to initialize properties in the class header. The arguments passed to the constructor are assigned to the properties. The syntax:

The secondary constructor is enclosed in the body of the class. Its syntax:

For example, imagine that you want to integrate an API developed by a smart device provider. The API returns a status code of

Inttype to indicate initial device status. The API returns a0if the device is offline and a1if the device is online. For any other integer value, the status is considered unknown. You can create a secondary constructor in theSmartDeviceclass to convert thisstatusCodeparameter to string representation:class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" constructor(name: String, category: String, statusCode: Int) : this(name, category) { deviceStatus = when (statusCode) { 0 -> "offline" 1 -> "online" else -> "unknown" } } ... }

Implement a relationship between classes¶

Inheritance lets you build a class upon the characteristics and behavior of another class. It helps you write reusable code and establish relationships between classes.

For example, there are many smart device types, such as smart TVs, smart lights, and smart switches. When you represent smart devices in programming, they share some common properties, such as a name, category, and status. They also have common behaviors, such as the ability to turn them on and off.

However, the way to turn on or turn off each smart device is different. For example, to turn on a TV, you might need to turn on the display, and then set up the last known volume level and channel. On the other hand, to turn on a light, you might only need to increase or decrease the brightness.

Also, each of the smart devices has more functions and actions that they can perform. For example, with a TV, you can adjust the volume and change the channel. With a light, you can adjust the brightness or color.

In short, all smart devices have different features, yet share some common characteristics. Duplicating these common characteristics to each of the smart device classes makes the difficult to maintain, hence we make the code reusable with inheritance.

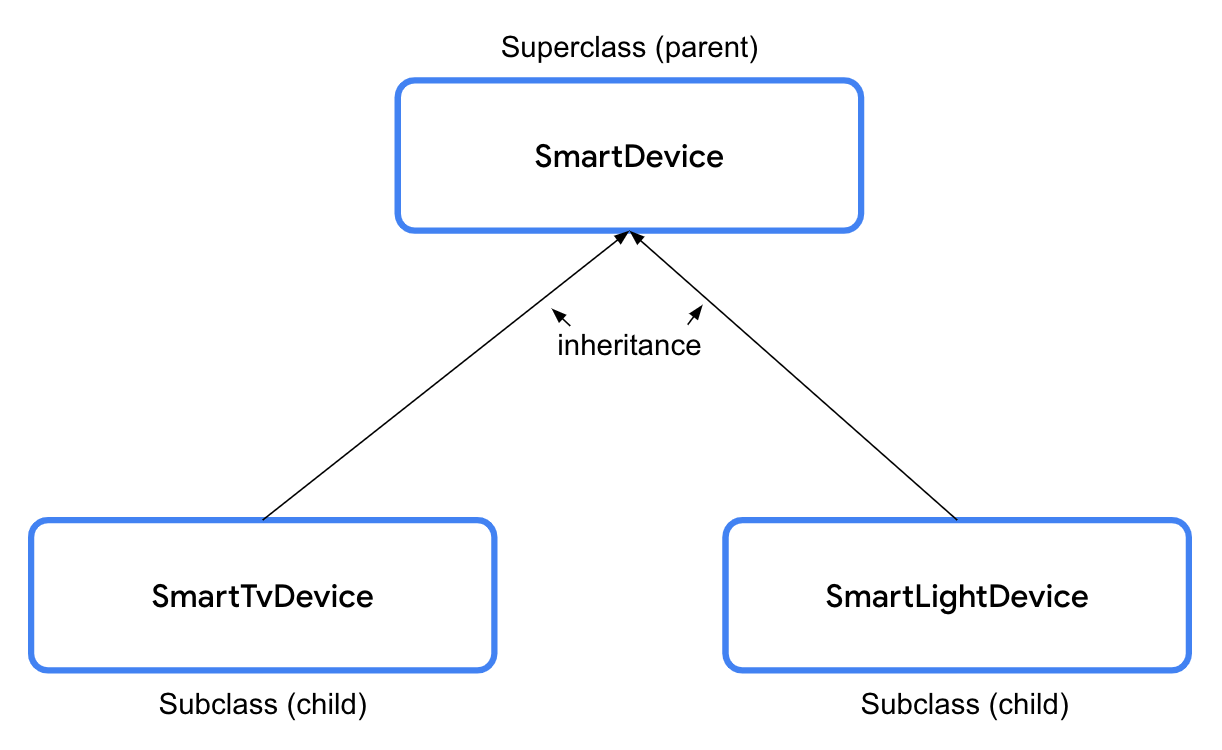

To do so, create a

SmartDeviceparent class, and define these common properties and behaviors. Then, create child classes, such as theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses, which inherit the properties of the parent class.In programming terms, we say that the

SmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses extend theSmartDeviceparent class. The parent class is also referred to as a superclass, and the child class as a subclass.

In Kotlin, all classes are final by default. Final means that you can’t extend them. To make a class extendable, it is necessary to use the

openkeyword.The

openkeyword informs the compiler that a class is extendable, so that other subclasses can extend it.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... }

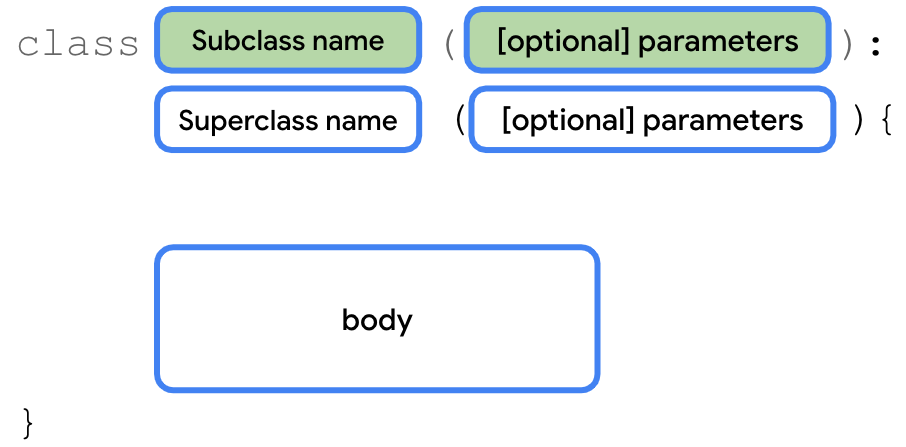

Syntax to extend a subclass from a superclass:

Example:

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { }

The constructor for

SmartTvDevicetakes in 2 parameters:deviceNameanddeviceCategory. These are simply passed on to the superclass constructorSmartDevice().The full

SmartTvDeviceclass might look like this:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } }

Sample code for the

SmartLightDeviceclass:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } }

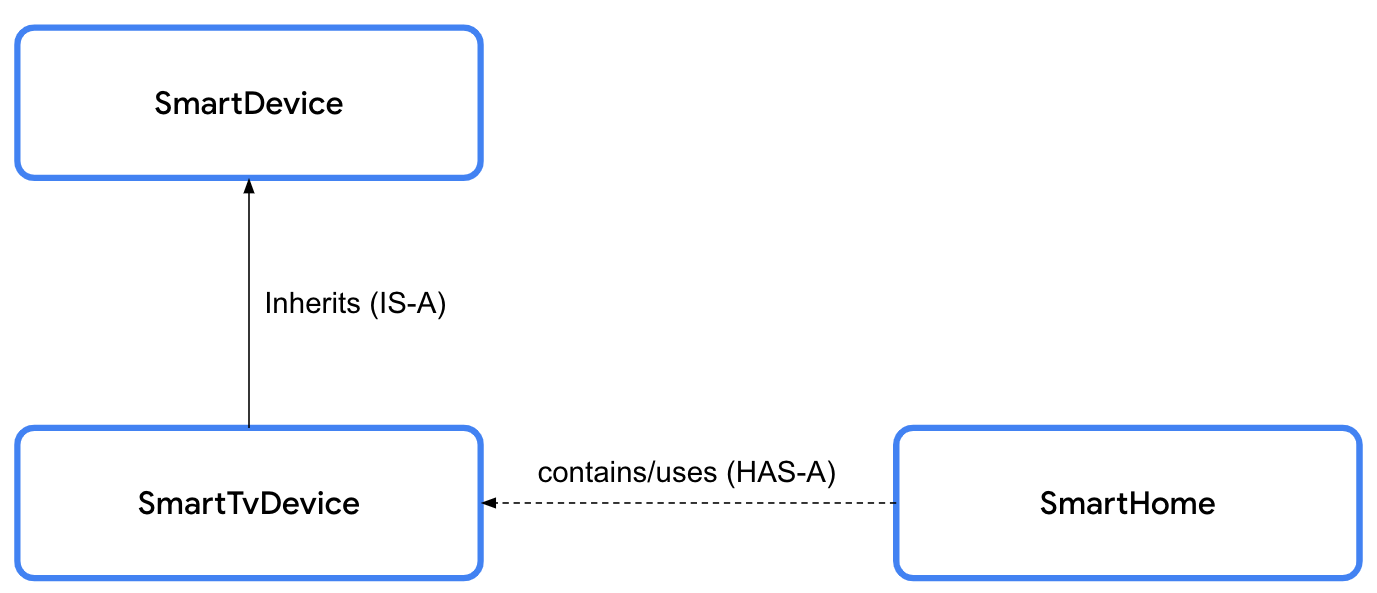

Inheritance establishes a relationship between two classes in something called an IS-A relationship. An object is also an instance of the class from which it inherits. In a HAS-A relationship, an object can own an instance of another class without actually being an instance of that class itself.

IS-A relationships: the

SmartDevicesuperclass andSmartTvDevicesubclass have an IS-A relationship. Whatever theSmartDevicesuperclass can do, theSmartTvDevicesubclass can do too. The relationship is unidirectional: every smart TV is a smart device, but not every smart device is a smart TV.Example of an IS-A relationship:

// Smart TV IS-A smart device. class SmartTvDevice : SmartDevice() { }

Don’t use inheritance only to achieve code reusability. Before you decide, check whether the two classes are related to each other. If they exhibit some relationship, check whether they really qualify for the IS-A relationship. Ask yourself, “Can I say a subclass is a superclass?”. For example, Android is an operating system.

HAS-A relationships: one class contains or uses another class. Example: a home has a smart TV. The HAS-A relationship is also known as composition.

The example below shows the

SmartHomeclass, which contains smart devices. TheSmartHomeclass lets us interact with the smart devices. The smart devices are theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDevice.class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { fun turnOnTv() { smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { smartTvDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseTvVolume() { smartTvDevice.increaseSpeakerVolume() } fun changeTvChannelToNext() { smartTvDevice.nextChannel() } fun turnOnLight() { smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { smartLightDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseLightBrightness() { smartLightDevice.increaseBrightness() } fun turnOffAllDevices() { turnOffTv() turnOffLight() } }

Override superclass methods from subclasses¶

Even though the turn-on and turn-off functionality is supported by all smart devices, the way in which the smart devices perform the functionality differs. To provide this device-specific behavior, you need to override the

turnOn()andturnOff()methods defined in the superclass. To override means to replace the code in the superclass with other code in the subclass.To make a method extendable, use the

openkeyword.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" open fun turnOn() { // function body } open fun turnOff() { // function body } }

The

overridekeyword informs the Kotlin runtime to execute the code enclosed in the method defined in the subclass.Sample code for the

SmartLightDeviceclass:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } }

Sample code for the

SmartTvDeviceclass:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is " + "set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" println("$name turned off") } }

This is an example of polymorphism. When the

turnOn()method of aSmartDevicevariable is called, depending on what the actual value of the variable is, different implementations of theturnOn()method can be executed.

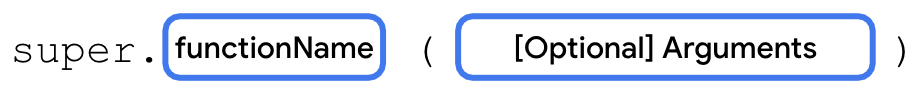

Reuse superclass code in subclasses¶

In the

turnOn()andturnOff()methods, there’s similarity in how thedeviceStatusvariable is updated, whenever the methods are called in theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDevicesubclasses. The code is duplicated. It would be better to put it in theSmartDeviceclass instead. Then, from the subclass, call the common code using thesuperkeyword.Syntax for a subclass to call a method from the superclass:

Sample code for the

SmartTvDevice:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() println("$name turned off") } }

Sample code for the

SmartLightDevice:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } }

Override superclass properties from subclasses¶

Properties can also be overridden in subclasses.

Example:

open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" open val deviceType = "unknown" ... }

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart TV" ... }

class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart Light" ... }

Visibility modifiers¶

Visibility modifiers play an important role to achieve encapsulation:

In a class, they let you hide your properties and methods from unauthorized access outside the class.

In a package, they let you hide the classes and interfaces from unauthorized access outside the package.

Note

A module is a collection of source files and build settings that let you divide your project into discrete units of functionality. Your project can have one or many modules. You can independently build, test, and debug each module.

A package is like a directory or a folder that groups related classes, whereas a module provides a container for your app’s source code, resource files, and app-level settings. A module can contain multiple packages.

Kotlin provides four visibility modifiers:

public: default visibility modifier. Makes the declaration accessible everywhere. The properties and methods that you want used outside the class are marked as public.private: makes the declaration accessible in the same class or source file. There are likely some properties and methods that are only used inside the class, and that you don’t necessarily want other classes to use. These properties and methods can be marked with the private visibility modifier to ensure that another class can’t accidentally access them.protected: makes the declaration accessible in subclasses. The properties and methods that you want used in the class that defines them and the subclasses are marked with the protected visibility modifier.internal: makes the declaration accessible in the same module. The internal modifier is similar to private, but you can access internal properties and methods from outside the class as long as it’s being accessed in the same module.

By default, a class is publicly visible, and can be accessed by any package that imports it. Similarly, when you define or declare properties and methods in the class, by default they can be accessed outside the class through the class object. It’s essential to define proper visibility for code, primarily to hide properties and methods that other classes don’t need to access.

Analogy: Only some parts of a car are exposed to a driver, not all. The specifics of what parts comprise the car and how the car works internally are hidden by default. The car is intended to be as intuitive to operate as possible. Drivers want to focus on driving, not on the internals of the car. Developers also want to know just enough to be able to use a class, they don’t want too much information.

Visibility modifiers help you expose only the relevant parts of the code to other classes in your project, and ensure that certain code cannot be unintentionally used, which makes for code that’s easy to understand and less prone to bugs.

Visibility modifier for properties¶

Syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a property:

Example:

open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... private var deviceStatus = "online" ... }

Syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a setter function:

For the

SmartDeviceclass, the value of thedeviceStatusproperty should be readable outside of the class through class objects. However, only the class and its children should be able to update or write the value. To implement this requirement, use the protected modifier on theset()function of thedeviceStatusproperty.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... var deviceStatus = "online" protected set(value) { field = value } ... }

The

set()function doesn’t performing any actions. It simply assigns thevalueparameter to thefieldvariable. This is similar to the default implementation for property setters, hence the parentheses and body ofset()can be omitted:open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... var deviceStatus = "online" protected set ... }

Code for the

SmartHomeclass, with a private setter fordeviceTurnOnCount:class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { var deviceTurnOnCount = 0 private set fun turnOnTv() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartTvDevice.turnOff() } ... fun turnOnLight() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartLightDevice.turnOff() } ... }

Visibility modifiers for methods¶

Syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a method:

Example:

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... protected fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } ... }

Visibility modifiers for constructors¶

Visibility modifiers for classes¶

Choosing visibility modifiers¶

Ideally, strive for strict visibility of properties and methods, and declare them with the

privatemodifier as often as possible. If you can’t keep them private, use theprotectedmodifier. If you can’t keep them protected, use theinternalmodifier. If you can’t keep theminternal, use thepublicmodifier.This table helps you determine the appropriate visibility modifiers based on where the property or methods of a class or constructor should be accessible:

Modifier

Accessible in same class

Accessible in subclass

Accessible in same module

Accessible outside module

private

✔

✘

✘

✘

protected

✔

✔

✘

✘

internal

✔

✔

✔

✘

public

✔

✔

✔

✔

In the

SmartTvDevicesubclass, you shouldn’t allow thespeakerVolumeandchannelNumberproperties to be controlled from outside the class. These properties should be controlled only through theincreaseSpeakerVolume()andnextChannel()methods.class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { private var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } private var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } ... }

Similarly, in the

SmartLightDevicesubclass, thebrightnessLevelproperty should be controlled only through theincreaseLightBrightness()method.class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... private var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } ... }

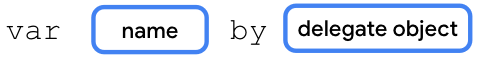

Define property delegates¶

Previously, we saw that properties in Kotlin use a backing field to hold their values in memory. The

fieldidentifier is used to reference it.Currently, there is some range-check code to check whether values are within range for the

speakerVolume,channelNumber, andbrightnessLevelproperties. The code is duplicated in theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses. We can reuse the range-check code in a setter function with delegates. Instead of using a field, and a getter and setter function to manage the value, a delegate object handles the getter and setter functions for the property.Syntax to create property delegates:

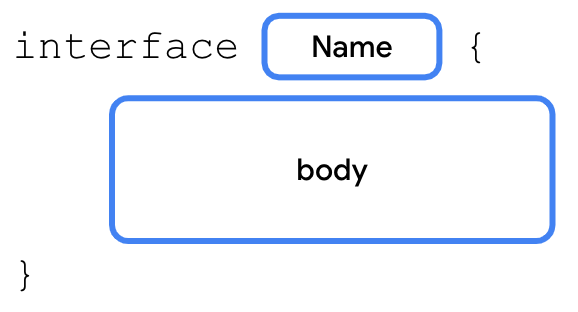

We’ll pause here and briefly explain interfaces. An interface is a contract. Classes that implement an interface need to adhere to this contract. It focuses on what to do instead of how to do the action. An interface helps to achieve abstraction.

For example, before building a house, you inform the architect about what you want. You want a bedroom, living room, kitchen, etc. In short, you specify what you want and the architect specifies how to achieve it.

Syntax to create an interface:

We’ve already learned how to extend a class and override its functionality. With interfaces, the class implements the interface. The class provides implementation details for the methods and properties declared in the interface. We’ll do something similar with the

ReadWritePropertyinterface to create the delegate.It’s ok if we’re still not clear about what interfaces are, we’ll learn more about interfaces later.

A delegate class for the

vartype implements theReadWritePropertyinterface. A delegate class for thevaltype implments theReadOnlyPropertyinterface.We’ll create a delegate class, the

RangeRegulatorclass that implements theReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int>interface. Ignore the<Any?, Int>for now, more on that later.class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { return fieldData } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { if (value in minValue..maxValue) { fieldData = value } } }

The

fieldDataproperty is acts as the backing field for the variable. It is initialized withinitialValueparameter.The

getValue()andsetValue()methods act as the property’s getter and setter functions.getValue()simply returns thefieldDataproperty.setValue()checks whether thevalueparameter is withinminValue..maxValue, before assigning it to thefieldDataproperty:

Note

KProperty is an interface that represents a declared property and lets you access the metadata on a delegated property. It’s out of scope of this mod. It’s enough to just have a high-level understanding about what the KProperty is.

Now, this range-check code can be re-used in the

SmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses. TheRangeRegulatorclass acts as a delegate for the properties that need range checking.In

SmartTvDevice:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... private var speakerVolume by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 2, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) private var channelNumber by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 1, minValue = 0, maxValue = 200) ... }

In

SmartLightDevice:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... private var brightnessLevel by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 0, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) ... }

Smart Home App code¶

Here’s the complete code for the Smart Home app.

import kotlin.properties.ReadWriteProperty import kotlin.reflect.KProperty open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" protected set open val deviceType = "unknown" open fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" } open fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" } } class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart TV" private var speakerVolume by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 2, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) private var channelNumber by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 1, minValue = 0, maxValue = 200) fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is " + "set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() println("$name turned off") } } class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart Light" private var brightnessLevel by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 0, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } } class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { var deviceTurnOnCount = 0 private set fun turnOnTv() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartTvDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseTvVolume() { smartTvDevice.increaseSpeakerVolume() } fun changeTvChannelToNext() { smartTvDevice.nextChannel() } fun turnOnLight() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartLightDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseLightBrightness() { smartLightDevice.increaseBrightness() } fun turnOffAllDevices() { turnOffTv() turnOffLight() } } class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { return fieldData } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { if (value in minValue..maxValue) { fieldData = value } } } fun main() { var smartDevice: SmartDevice = SmartTvDevice("Android TV", "Entertainment") smartDevice.turnOn() smartDevice = SmartLightDevice("Google Light", "Utility") smartDevice.turnOn() }

Practice: Classes and Objects¶

If you need more practice, do these exercises. If not, feel free to skip them.

In the

SmartDeviceclass, define aprintDeviceInfo()method that prints a"Device name: $name, category: $category, type: $deviceType"string.In the

SmartTvDeviceclass, define adecreaseVolume()method that decreases the volume and apreviousChannel()method that navigates to the previous channel.In the

SmartLightDeviceclass, define adecreaseBrightness()method that decreases the brightness.In the

SmartHomeclass, ensure that all actions can only be performed when each device’sdeviceStatusproperty is set to an"on"string. Also, ensure that thedeviceTurnOnCountproperty is updated correctly.In the

SmartHomeclass, define andecreaseTvVolume(),changeTvChannelToPrevious(),printSmartTvInfo(),printSmartLightInfo(), anddecreaseLightBrightness()method.Call the appropriate methods from the

SmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses in theSmartHomeclass.In the

main()function, call these added methods to test them.

Summary¶

There are four main principles of OOP: encapsulation, abstraction, inheritance, and polymorphism.

Classes are defined with the

classkeyword, and contain properties and methods.Properties are similar to variables except properties can have custom getters and setters.

A constructor specifies how to instantiate objects of a class.

You can omit the

constructorkeyword when you define a primary constructor.Inheritance makes it easier to reuse code.

The IS-A relationship refers to inheritance.

The HAS-A relationship refers to composition.

Visibility modifiers play an important role in the achievement of encapsulation.

Kotlin provides four visibility modifiers: the

public,private,protected, andinternalmodifiers.A property delegate lets you reuse the getter and setter code in multiple classes.

Use function types and lambda expressions¶

In Kotlin, functions are considered first-class constructs. This means that functions can be treated as a data type. You can store functions in variables, pass them to other functions as arguments, and return them from other functions.

Data types can store literal values — an

Inttype can store a10literal value, aStringtype can store a"Hello"literal value, etc. We can also declare function literals, which are called lambda expressions or lambdas for short.

Store a function in a variable¶

So far, we’ve learned how to declare functions with the

funkeyword. A function can be called, which causes the code in the function body to execute.As a first-class construct, functions are also data types, so you can store functions in variables, pass them to functions, and return them from functions. All this is made possible by lambda expressions.

We’ll see this in action with some trick-or-treating code, which refers to a tradition in many countries during which children dressed in costumes go from door to door and ask, “trick or treat?”. It helps if you try the code examples in Kotlin Playground.

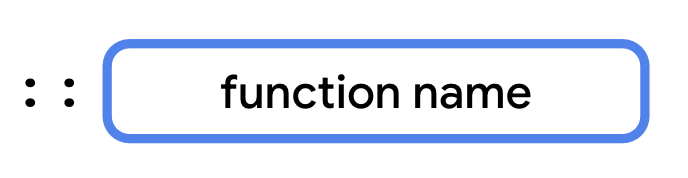

Syntax to refer to a function as a value:

Example:

fun main() { val trickFunction = ::trick } fun trick() { println("No treats!") }

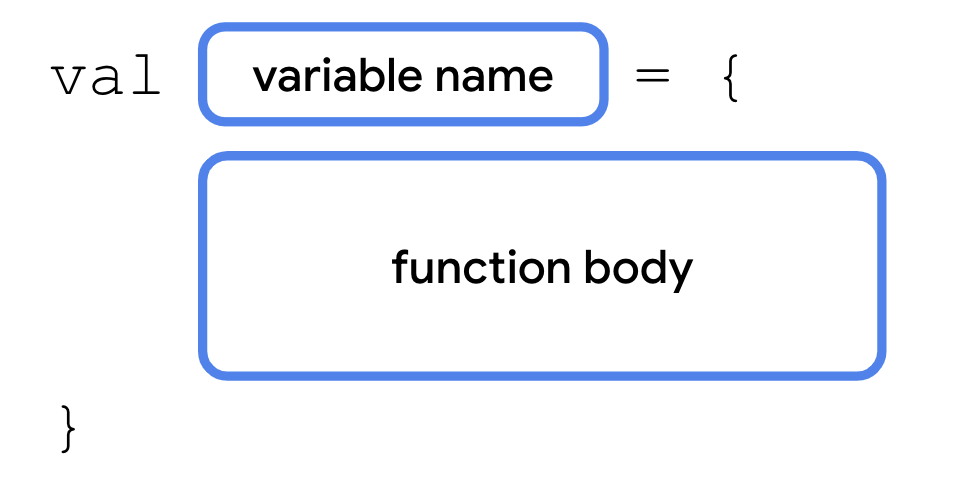

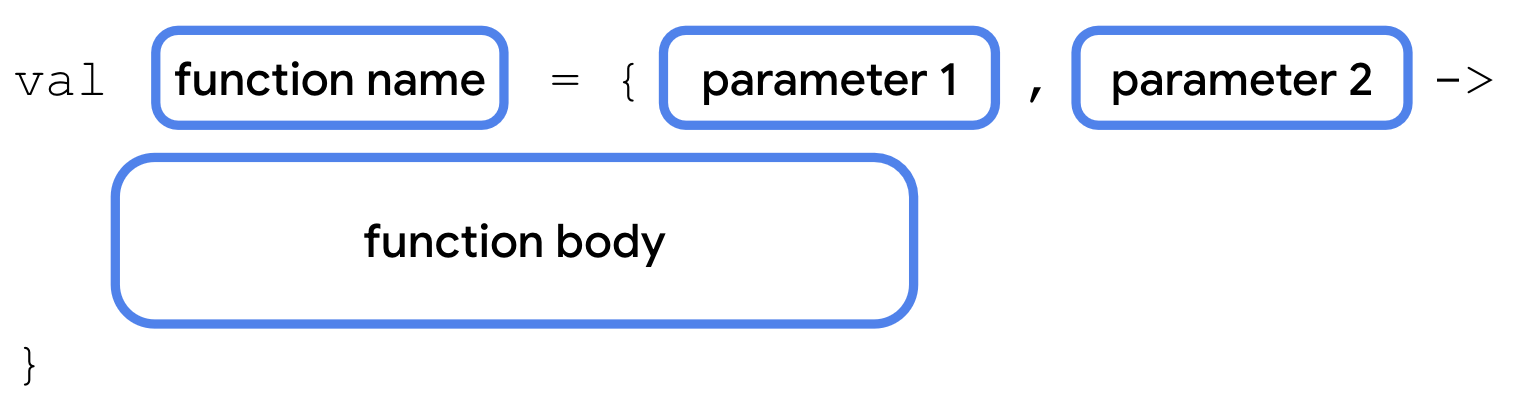

Lambda expressions provide a concise syntax to define a function without the

funkeyword. You can store a lambda expression directly in a variable.Syntax for lambda expressions:

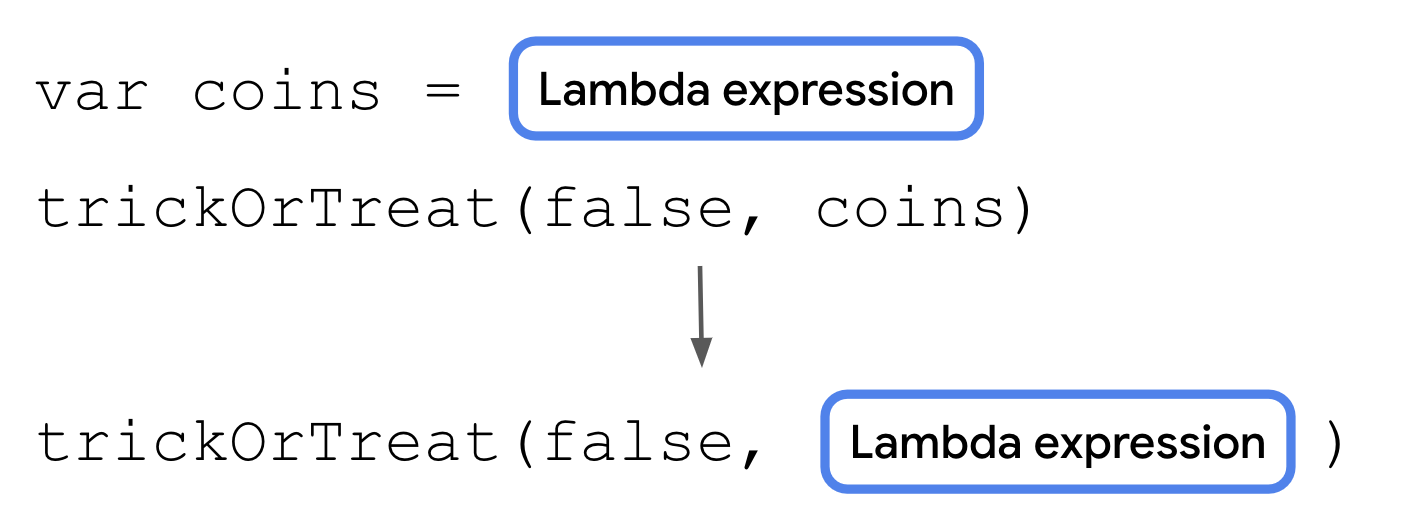

When defining a function with a lambda expression, a variable is used to refer to the function. Example:

fun main() { val trickFunction = trick trick() trickFunction() } val trick = { println("No treats!") }

Using type inference, the Kotlin compiler inferred that the type of

trickis a function. Next up, we’ll learn how to explicitly specify function types.

Use functions as a data type¶

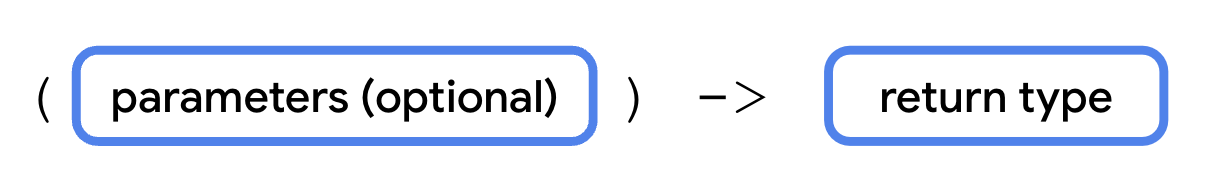

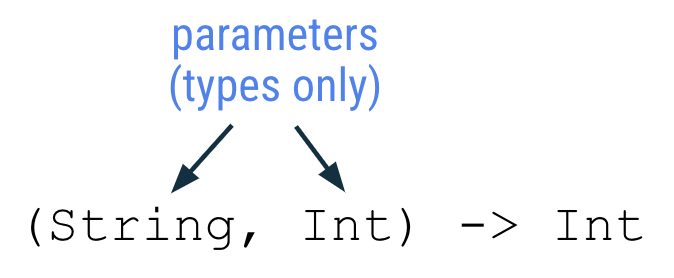

Syntax for function types:

Examples:

() -> Unit: a function that doesn’t take any parameters, and doesn’t return anything(Int, Int) -> String: a function that takes twoIntparameters, and returns aString

In the code below,

treat()behaves liketrick(). Both variables have the same data type, even though only thetreatvariable declares it explicitly. The type oftrickis inferred using type inference.val trick = { println("No treats!") } val treat: () -> Unit = { println("Have a treat!") } fun main() { val trickFunction = trick trick() trickFunction() treat() }

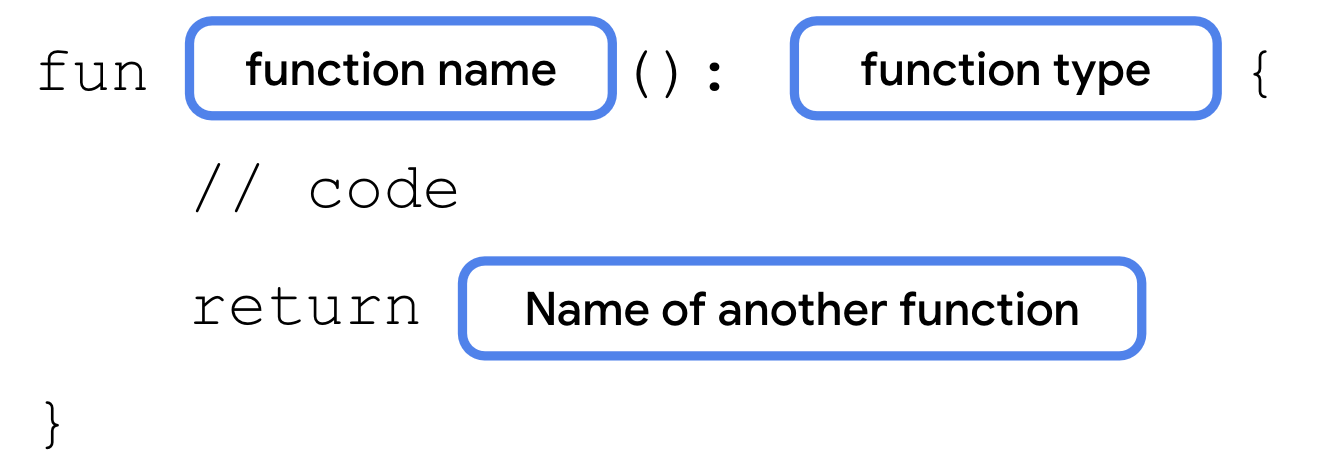

Use a function as a return type¶

A function is a data type, so you can use it like any other data type. You can even return functions from other functions.

Syntax for using a function type as a return type:

In this example, the

trickOrTreat()function returns another function. The returned function is of type() -> Unit.fun main() { val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false) val trickFunction = trickOrTreat(true) treatFunction() trickFunction() } fun trickOrTreat(isTrick: Boolean): () -> Unit { if (isTrick) { return trick } else { return treat } } val trick = { println("No treats!") } val treat = { println("Have a treat!") }

Pass a function to another function as an argument¶

We’ll modify the

trickOrTreat()function to allow an extra treat. The extra treat will be represented by a function. This function will be provided as an argument totrickOrTreat().Syntax for specifying a function type as a parameter to another function:

Syntax for writing a lambda expression for a function that takes a parameter (the function type is omitted):

Example:

fun main() { val coins: (Int) -> String = { quantity -> "$quantity quarters" } val cupcake: (Int) -> String = { "Have a cupcake!" } val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false, coins) val trickFunction = trickOrTreat(true, cupcake) treatFunction() trickFunction() } fun trickOrTreat(isTrick: Boolean, extraTreat: (Int) -> String): () -> Unit { if (isTrick) { return trick } else { println(extraTreat(5)) return treat } } val trick = { println("No treats!") } val treat = { println("Have a treat!") }

Let’s zoom in on this code:

val coins: (Int) -> String = { quantity -> "$quantity quarters" }

The code creates a

coinsvariable. The variable can contain a function.The

(Int) -> Stringmeans this function takes anIntparameter, and returns aString.The

Intparameter is namedquantity. This could be named anything you like.The return value is a

Stringthat contains thequantityparameter and the wordquarters.

Let’s zoom in on this code:

val cupcake: (Int) -> String = { "Have a cupcake!" }

The code creates a

cupcakevariable. The variable can contain a function.The

(Int) -> Stringmeans this function takes anIntparameter, and returns aString.The

Intparameter is not used in the function, which is fine. That’s why it’s missing thequantity -> ``, unlike the ``coins()function.It always returns the string

Have a cupcake!

Finally, let’s zoom in on this code:

fun trickOrTreat(isTrick: Boolean, extraTreat: (Int) -> String): () -> Unit { if (isTrick) { return trick } else { println(extraTreat(5)) return treat } }

The code declares a function named

trickOrTreat. The function takes 2 parameters.The

isTrickparameter has aBooleantype.The

extraTreatparameter has a(Int) -> Stringtype, meaning it can hold a function that takes anIntparameter, and returns aString.The

trickOrTreatfunction has a return type() -> Unit, which means it returns a function that takes no parameters and returns nothing.

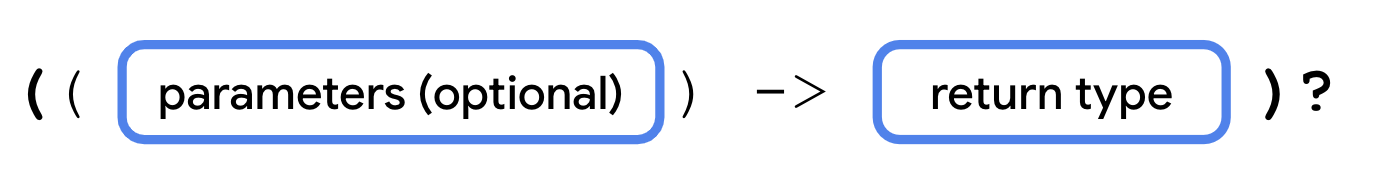

Nullable function types¶

Like other data types, function types can be declared as nullable. In these cases, a variable could contain a function or it could be

null.Syntax to declare a function as nullable:

For example, to make the

extraTreatparameter nullable so that you don’t have to provide anextraTreat()function every time that you call thetrickOrTreat()function:fun trickOrTreat(isTrick: Boolean, extraTreat: ((Int) -> String)?): () -> Unit { if (isTrick) { return trick } else { if (extraTreat != null) { println(extraTreat(5)) } return treat } } fun main() { val coins: (Int) -> String = { quantity -> "$quantity quarters" } val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false, coins) val trickFunction = trickOrTreat(true, null) treatFunction() trickFunction() } val trick = { println("No treats!") } val treat = { println("Have a treat!") }

Write lambda expressions with shorthand syntax¶

Lambda expressions make code more concise. We’ll explore some shorthand syntax to write lambda expressions more concisely.

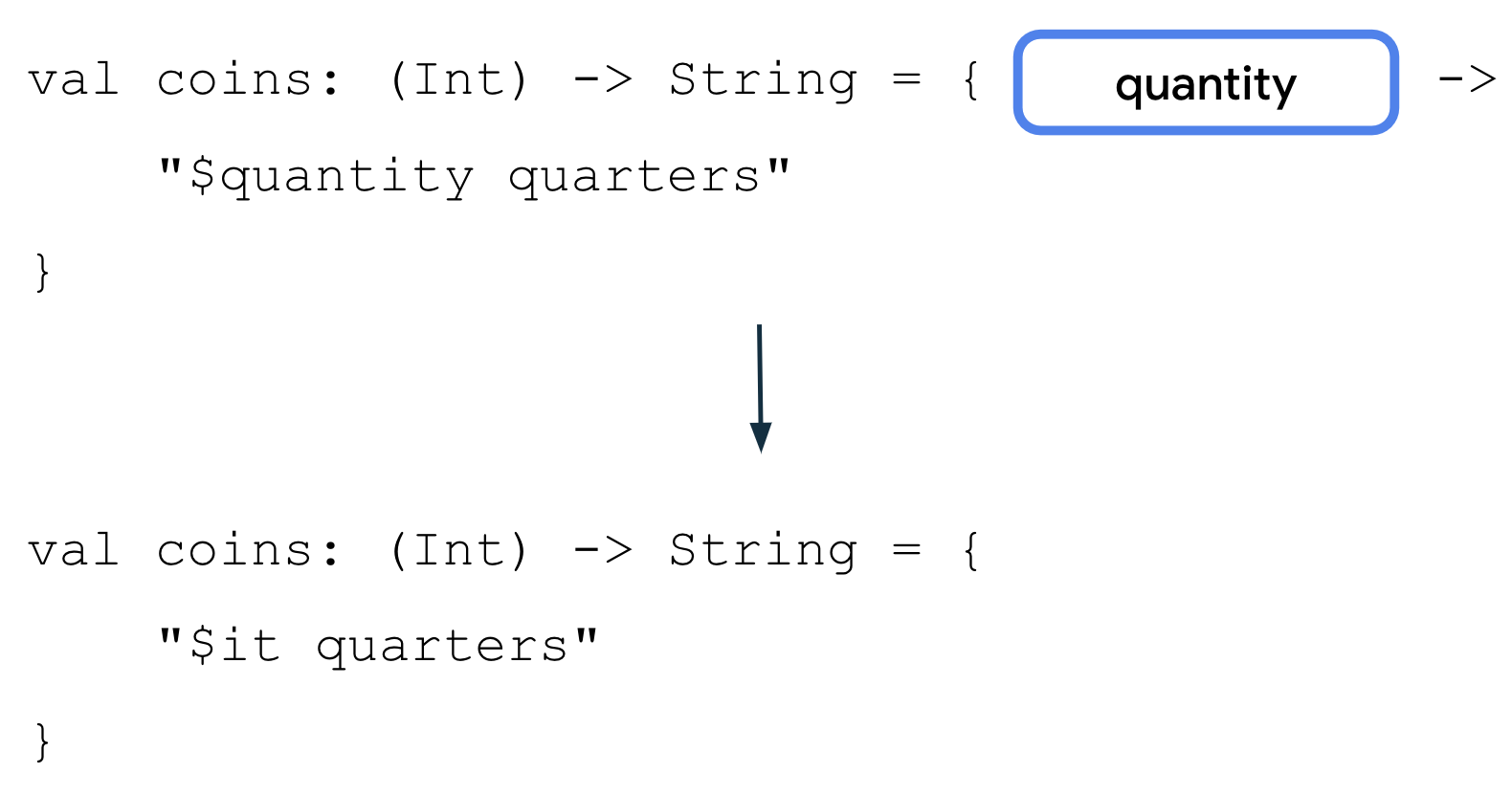

Omit parameter name¶

When a function has a single parameter and you don’t provide a name, Kotlin implicitly assigns it the

itname, so you can omit the parameter name and->symbol, which makes your lambda expressions more concise.Syntax for omitting the parameter name:

Example:

val coins: (Int) -> String = { "$it quarters" }

$itcan only be used for a single parameter. If a lambda expression has multiple parameters, they must be explicitly named.

Pass a lambda expression directly into a function¶

The

coins()function is currently only used in one place:val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false, coins)

Instead of creating a variable to store it, it’s also possible to pass a lambda expression directly into

trickOrTreat():val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false, LAMBDA_EXPRESSION)

Lambda expressions are simply function literals, just like

0is an integer literal, and"Slay"is a string literal. You can pass a lambda expression directly into a function call.Syntax to pass a lambda expression into a function call:

Example:

fun main() { val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false, { "$it quarters" }) val trickFunction = trickOrTreat(true, null) treatFunction() trickFunction() }

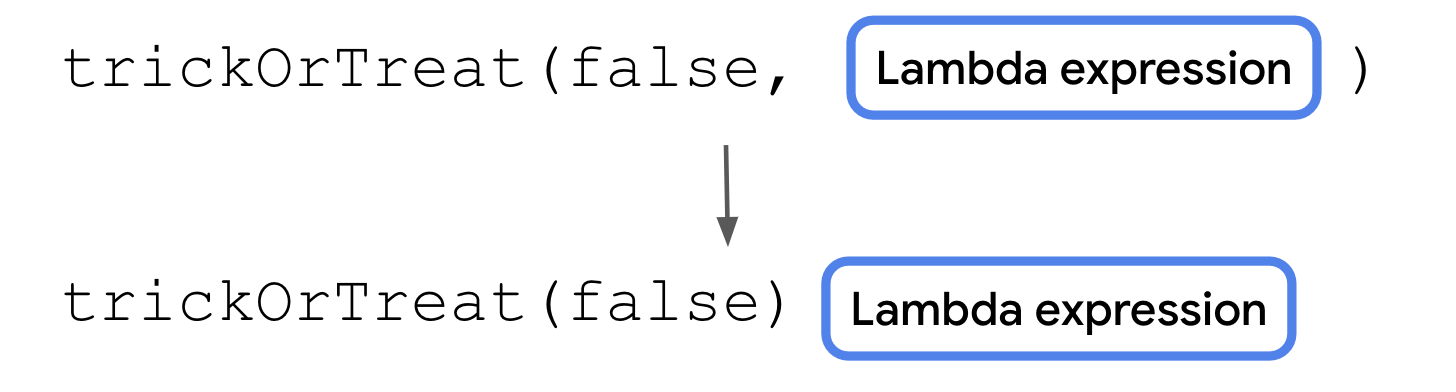

Use trailing lambda syntax¶

When a function type is the last parameter of a function, you can write lambdas using another shorthand option.

Syntax for trailing lambdas:

This makes code more readable because it separates the lambda expression from the other parameters, but doesn’t change what the code does.

Example:

val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false) { "$it quarters" }

Note

Composable functions are typically called using trailing lambda syntax.

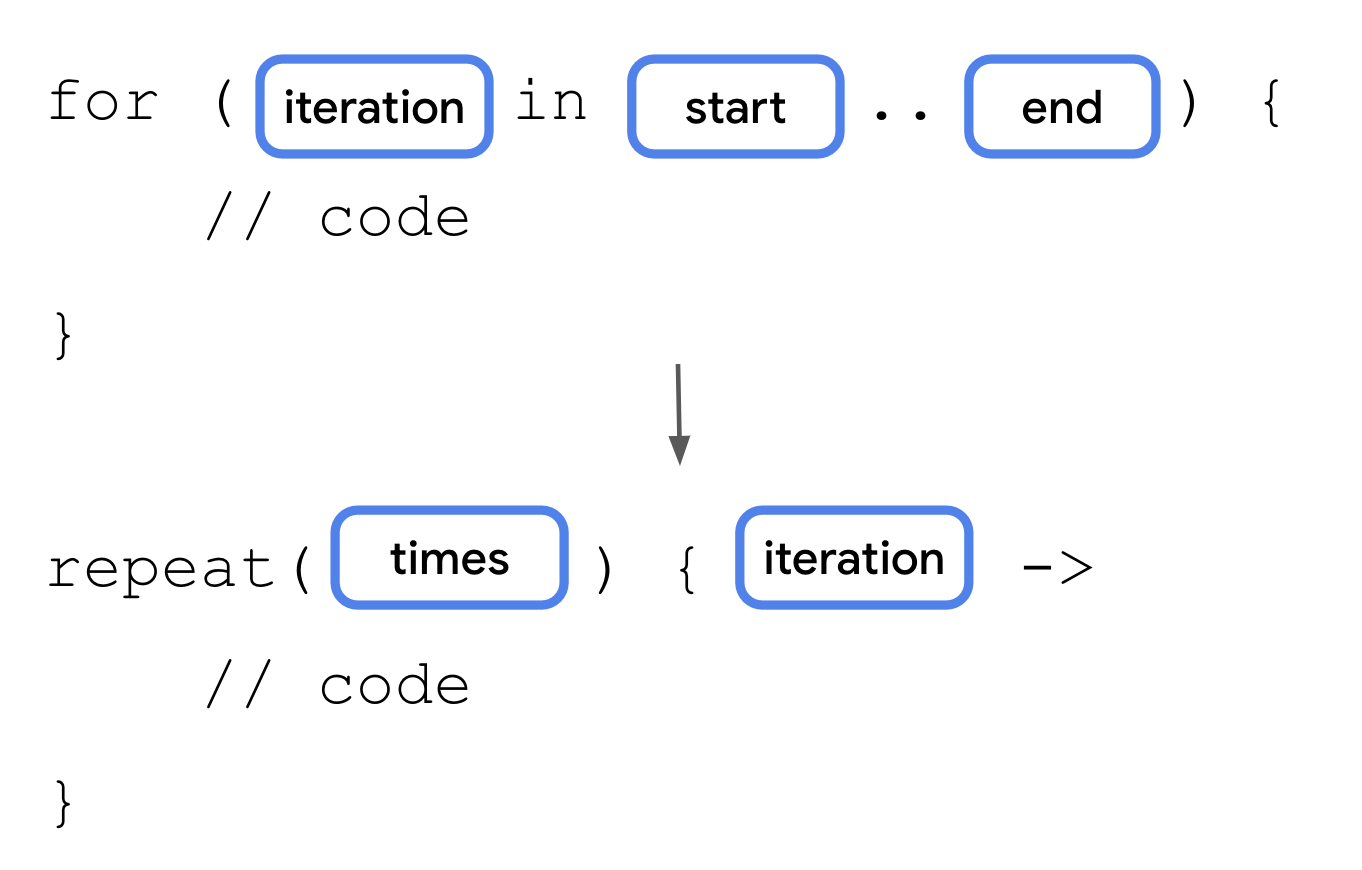

Use the repeat() function¶

A higher-order function either returns a function, and/or takes a function as an argument. The

trickOrTreat()function is an example of a higher-order function, because it takes a function of type((Int) -> String)?as a parameter and returns a function of type() -> Unit.Kotlin provides several useful higher-order functions. The

repeat()function is one such higher-order function. It’s basically a for loop. The function signature:repeat(times: Int, action: (Int) -> Unit)

The

timesparameter is the number of times that the action should happen. Theactionparameter is a function that takes a singleIntparameter and returns aUnittype.The

repeat()function is used to repeat code a specified number of times, similar to aforloop:

Instead of calling the

trickFunction()function only once, you can call it multiple times with therepeat()function.Example:

fun main() { val treatFunction = trickOrTreat(false) { "$it quarters" } val trickFunction = trickOrTreat(true, null) repeat(4) { treatFunction() } trickFunction() }

Practice: Kotlin Fundamentals¶

Need some extra practice? These exercises test your understanding of the concepts that you studied. They’re based on real-world use cases, some of which you probably encountered before as a user.

If you don’t need any extra practice, feel free to skip these exercises.

Sample solutions are provided. The solutions are only one way to solve the exercises, so feel free to experiment however you feel comfortable.

Mobile notifications¶

Typically, your phone provides you with a summary of notifications.

Using the starter code below, write a program that prints the summary message based on the number of notifications received. The message should include:

The exact number of notifications when there are less than 100 notifications.

99+as the number of notifications when there are 100 notifications or more.

fun main() { val morningNotification = 51 val eveningNotification = 135 printNotificationSummary(morningNotification) printNotificationSummary(eveningNotification) } fun printNotificationSummary(numberOfMessages: Int) { // Fill in the code. }

Complete the printNotificationSummary() function so that the program prints these lines:

You have 51 notifications. Your phone is blowing up! You have 99+ notifications.

Movie ticket price¶

Movie tickets are typically priced differently based on the age of moviegoers.

Using the starter code below, write a program that calculates these age-based ticket prices:

A children’s ticket price of $15 for people 12 years old or younger.

A standard ticket price of $30 for people between 13 and 60 years old. On Mondays, discount the standard ticket price to $25 for this same age group.

A senior ticket price of $20 for people 61 years old and older. Assume that the maximum age of a moviegoer is 100 years old.

A

-1to indicate that the price is invalid when a user inputs an age outside of the age specifications.

fun main() { val child = 5 val adult = 28 val senior = 87 val isMonday = true println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $child is $${ticketPrice(child, isMonday)}.") println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $adult is $${ticketPrice(adult, isMonday)}.") println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $senior is $${ticketPrice(senior, isMonday)}.") } fun ticketPrice(age: Int, isMonday: Boolean): Int { // Fill in the code. }

Complete the ticketPrice() function so that the program prints these lines:

The movie ticket price for a person aged 5 is $15. The movie ticket price for a person aged 28 is $25. The movie ticket price for a person aged 87 is $20.

Temperature converter¶

There are three main temperature scales used in the world: Celsius, Fahrenheit, and Kelvin.

Using the starter code below, write a program that converts a temperature from one scale to another with these formulas:

Celsius to Fahrenheit: ° F = 9/5 (° C) + 32

Kelvin to Celsius: ° C = K - 273.15

Fahrenheit to Kelvin: K = 5/9 (° F - 32) + 273.15

Note that the

String.format("%.2f", /* measurement */ )method is used to convert a number into aStringtype with 2 decimal places.fun main() { // Fill in the code. } fun printFinalTemperature( initialMeasurement: Double, initialUnit: String, finalUnit: String, conversionFormula: (Double) -> Double ) { val finalMeasurement = String.format("%.2f", conversionFormula(initialMeasurement)) // two decimal places println("$initialMeasurement degrees $initialUnit is $finalMeasurement degrees $finalUnit.") }

Complete the

main()function so that it calls theprintFinalTemperature()function and prints the following lines. You need to pass arguments for the temperature and conversion formula. Hint: you may want to useDoublevalues to avoidIntegertruncation during division operations.27.0 degrees Celsius is 80.60 degrees Fahrenheit. 350.0 degrees Kelvin is 76.85 degrees Celsius. 10.0 degrees Fahrenheit is 260.93 degrees Kelvin.

Song catalog¶

Imagine that you need to create a music-player app.

Create a class that can represent the structure of a song. The

Songclass must include these code elements:Properties for the title, artist, year published, and play count

A property that indicates whether the song is popular. If the play count is less than 1,000, consider it unpopular.

A method that prints a song description in this format:

“[Title], performed by [artist], was released in [year published].”

Internet profile¶

Oftentimes, you’re required to complete profiles for online websites that contain mandatory and non-mandatory fields. For example, you can add your personal information and link to other people who referred you to sign up for the profile.

Using the starter code below, write a program which prints out a person’s profile details.

fun main() { val amanda = Person("Amanda", 33, "play tennis", null) val atiqah = Person("Atiqah", 28, "climb", amanda) amanda.showProfile() atiqah.showProfile() } class Person(val name: String, val age: Int, val hobby: String?, val referrer: Person?) { fun showProfile() { // Fill in code } }

Sample output:

Name: Amanda Age: 33 Likes to play tennis. Doesn't have a referrer. Name: Atiqah Age: 28 Likes to climb. Has a referrer named Amanda, who likes to play tennis.

Foldable phones¶

Typically, a phone screen turns on and off when the power button is pressed. In contrast, if a foldable phone is folded, the main inner screen on a foldable phone doesn’t turn on when the power button is pressed.

Using the starter code below, write a

FoldablePhoneclass that inherits from thePhoneclass. It should contain the following:A property that indicates whether the phone is folded.

A different

switchOn()function behavior than thePhoneclass so that it only turns the screen on when the phone isn’t folded.Methods to change the folding state.

class Phone(var isScreenLightOn: Boolean = false){ fun switchOn() { isScreenLightOn = true } fun switchOff() { isScreenLightOn = false } fun checkPhoneScreenLight() { val phoneScreenLight = if (isScreenLightOn) "on" else "off" println("The phone screen's light is $phoneScreenLight.") } }

Special auction¶

Typically in an auction, the highest bidder determines the price of an item. In this special auction, if there’s no bidder for an item, the item is automatically sold to the auction house at the minimum price.

In the starter code below, you’re given an

auctionPrice()function that accepts a nullableBid?type as an argument:fun main() { val winningBid = Bid(5000, "Private Collector") println("Item A is sold at ${auctionPrice(winningBid, 2000)}.") println("Item B is sold at ${auctionPrice(null, 3000)}.") } class Bid(val amount: Int, val bidder: String) fun auctionPrice(bid: Bid?, minimumPrice: Int): Int { // Fill in the code. }

Complete the

auctionPrice()function so that the program prints these lines:Item A is sold at 5000. Item B is sold at 3000.

Solution code¶

Solution: Mobile notifications¶

The solution uses an

if/elsestatement to print the appropriate notification summary message based on the number of notification messages received:fun main() { val morningNotification = 51 val eveningNotification = 135 printNotificationSummary(morningNotification) printNotificationSummary(eveningNotification) } fun printNotificationSummary(numberOfMessages: Int) { if (numberOfMessages < 100) { println("You have ${numberOfMessages} notifications.") } else { println("Your phone is blowing up! You have 99+ notifications.") } }

Solution: Movie ticket price¶

The solution uses a

whenexpression to return the appropriate ticket price based on the moviegoer’s age. It also uses a simpleif/elseexpression for one of thewhenexpression’s branches to add the additional condition for the standard ticket pricing.The ticket price in the

elsebranch returns a-1value, which indicates that the price set is invalid for theelsebranch. A better implementation is for theelsebranch to throw an exception. You learn about exception handling in future units.fun main() { val child = 5 val adult = 28 val senior = 87 val isMonday = true println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $child is \$${ticketPrice(child, isMonday)}.") println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $adult is \$${ticketPrice(adult, isMonday)}.") println("The movie ticket price for a person aged $senior is \$${ticketPrice(senior, isMonday)}.") } fun ticketPrice(age: Int, isMonday: Boolean): Int { return when(age) { in 0..12 -> 15 in 13..60 -> if (isMonday) 25 else 30 in 61..100 -> 20 else -> -1 } }

Solution: Temperature converter¶

The solution requires you to pass a function as a parameter to the

printFinalTemperature()function. The most succinct solution passes lambda expressions as the arguments, uses theitparameter reference in place of the parameter names, and makes use of trailing lambda syntax.fun main() { printFinalTemperature(27.0, "Celsius", "Fahrenheit") { 9.0 / 5.0 * it + 32 } printFinalTemperature(350.0, "Kelvin", "Celsius") { it - 273.15 } printFinalTemperature(10.0, "Fahrenheit", "Kelvin") { 5.0 / 9.0 * (it - 32) + 273.15 } } fun printFinalTemperature( initialMeasurement: Double, initialUnit: String, finalUnit: String, conversionFormula: (Double) -> Double ) { val finalMeasurement = String.format("%.2f", conversionFormula(initialMeasurement)) // two decimal places println("$initialMeasurement degrees $initialUnit is $finalMeasurement degrees $finalUnit.") }

Solution: Song catalog¶

The solution contains a

Songclass with a default constructor that accepts all required parameters. TheSongclass also has anisPopularproperty that uses a custom getter function, and a method that prints the description of itself. You can create an instance of the class in themain()function and call its methods to test whether the implementation is correct. You can use underscores when writing large numbers such as the1_000_000value to make it more readable.fun main() { val brunoSong = Song("We Don't Talk About Bruno", "Encanto Cast", 2022, 1_000_000) brunoSong.printDescription() println(brunoSong.isPopular) } class Song( val title: String, val artist: String, val yearPublished: Int, val playCount: Int ){ val isPopular: Boolean get() = playCount >= 1000 fun printDescription() { println("$title, performed by $artist, was released in $yearPublished.") } }

When you call the

println()function on the instance’s methods, the program may print this output:We Don't Talk About Bruno, performed by Encanto Cast, was released in 2022. true

Solution: Internet profile¶

The solution contains

nullchecks in variousif/elsestatements to print different text based on whether various class properties arenull:fun main() { val amanda = Person("Amanda", 33, "play tennis", null) val atiqah = Person("Atiqah", 28, "climb", amanda) amanda.showProfile() atiqah.showProfile() } class Person(val name: String, val age: Int, val hobby: String?, val referrer: Person?) { fun showProfile() { println("Name: $name") println("Age: $age") if(hobby != null) { print("Likes to $hobby. ") } if(referrer != null) { print("Has a referrer named ${referrer.name}") if(referrer.hobby != null) { print(", who likes to ${referrer.hobby}.") } else { print(".") } } else { print("Doesn't have a referrer.") } print("\n\n") } }

Solution: Foldable phones¶

For the

Phoneclass to be a parent class, you need to make the class open by adding theopenkeyword before the class name. To override theswitchOn()method in the FoldablePhone class, you need to make the method in thePhoneclass open by adding theopenkeyword before the method.The solution contains a

FoldablePhoneclass with a default constructor that contains a default argument for theisFoldedparameter. TheFoldablePhoneclass also has two methods to change theisFoldedproperty to either atrueorfalsevalue. It also overrides theswitchOn()method inherited from thePhoneclass.You can create an instance of the class in the

main()function and call its methods to test if the implementation is correct.open class Phone(var isScreenLightOn: Boolean = false){ open fun switchOn() { isScreenLightOn = true } fun switchOff() { isScreenLightOn = false } fun checkPhoneScreenLight() { val phoneScreenLight = if (isScreenLightOn) "on" else "off" println("The phone screen's light is $phoneScreenLight.") } } class FoldablePhone(var isFolded: Boolean = true): Phone() { override fun switchOn() { if (!isFolded) { isScreenLightOn = true } } fun fold() { isFolded = true } fun unfold() { isFolded = false } } fun main() { val newFoldablePhone = FoldablePhone() newFoldablePhone.switchOn() newFoldablePhone.checkPhoneScreenLight() newFoldablePhone.unfold() newFoldablePhone.switchOn() newFoldablePhone.checkPhoneScreenLight() }

The output is the following:

The phone screen's light is off. The phone screen's light is on.

Solution: Special auction¶

The solution uses the

?.safe call operator and the?:Elvis operator to return the correct price:fun main() { val winningBid = Bid(5000, "Private Collector") println("Item A is sold at ${auctionPrice(winningBid, 2000)}.") println("Item B is sold at ${auctionPrice(null, 3000)}.") } class Bid(val amount: Int, val bidder: String) fun auctionPrice(bid: Bid?, minimumPrice: Int): Int { return bid?.amount ?: minimumPrice }

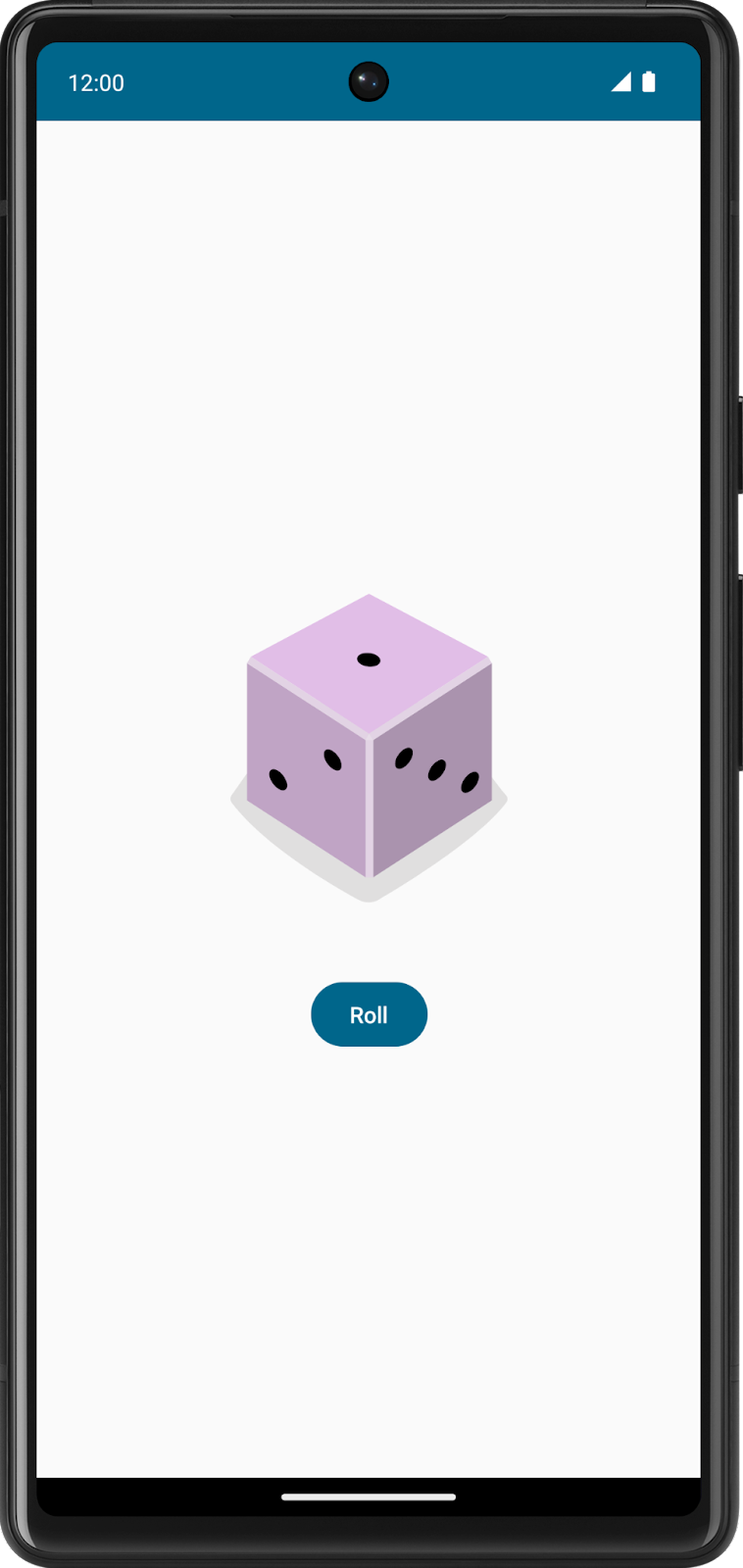

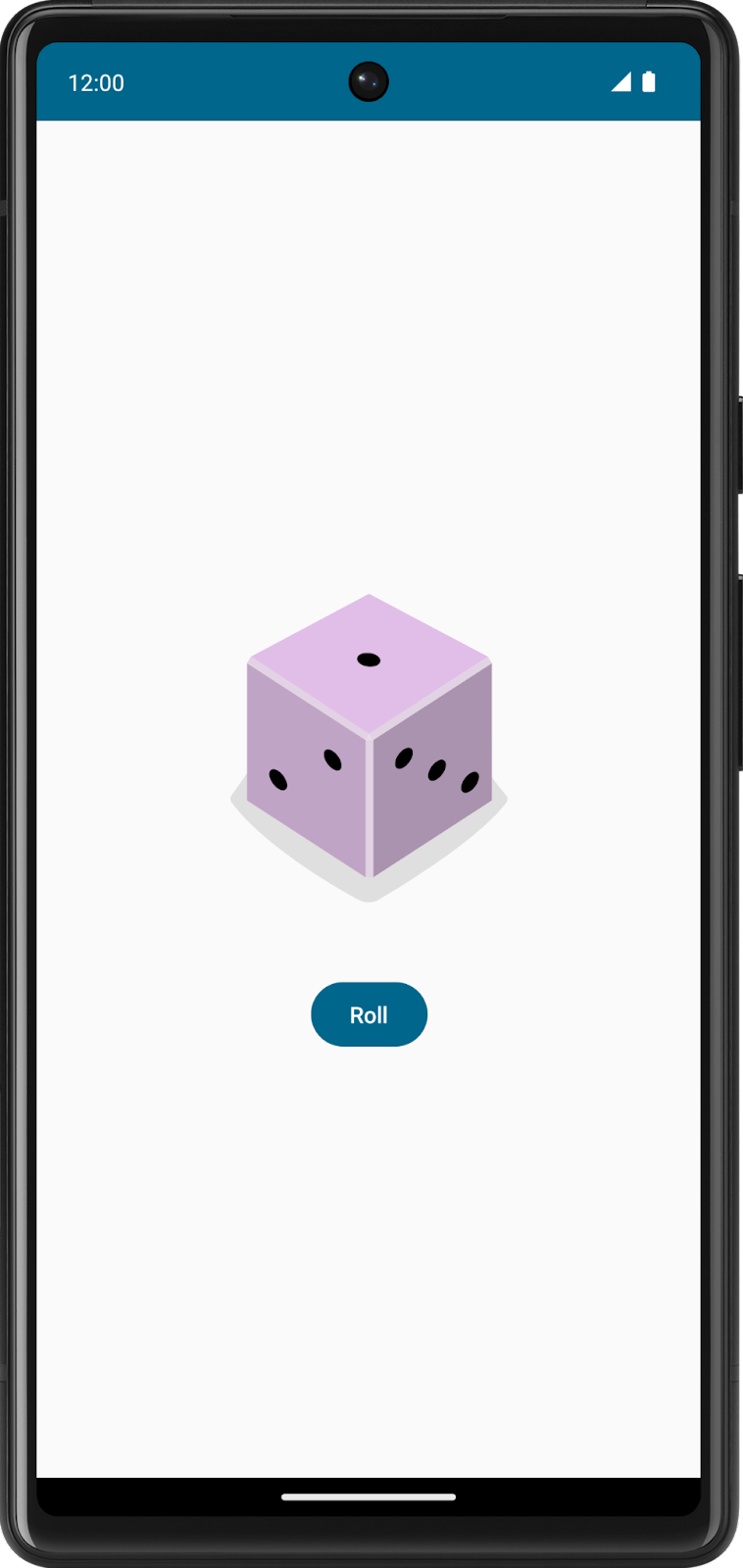

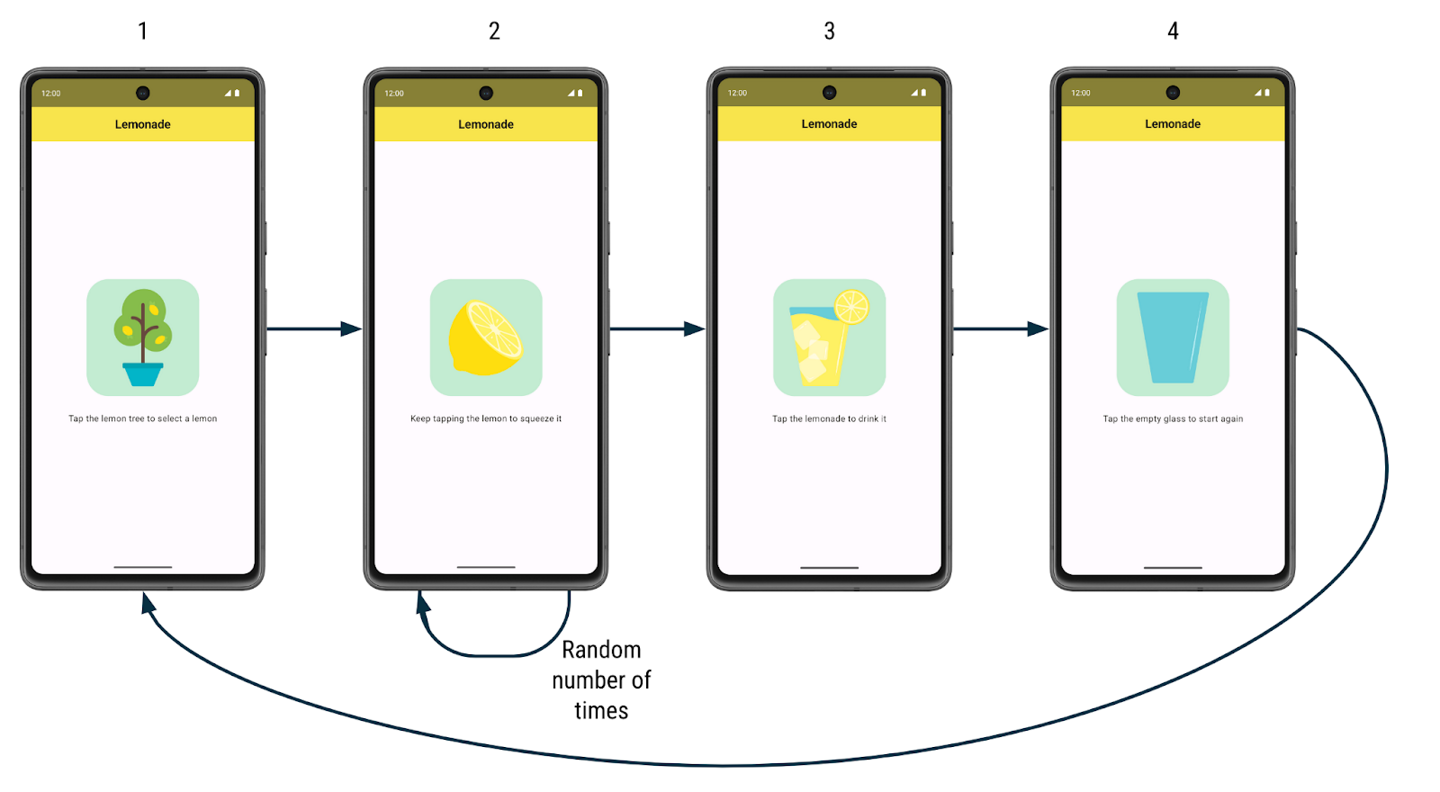

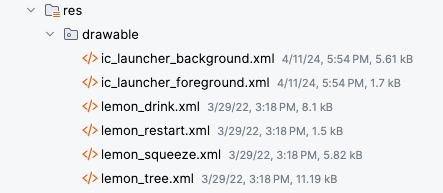

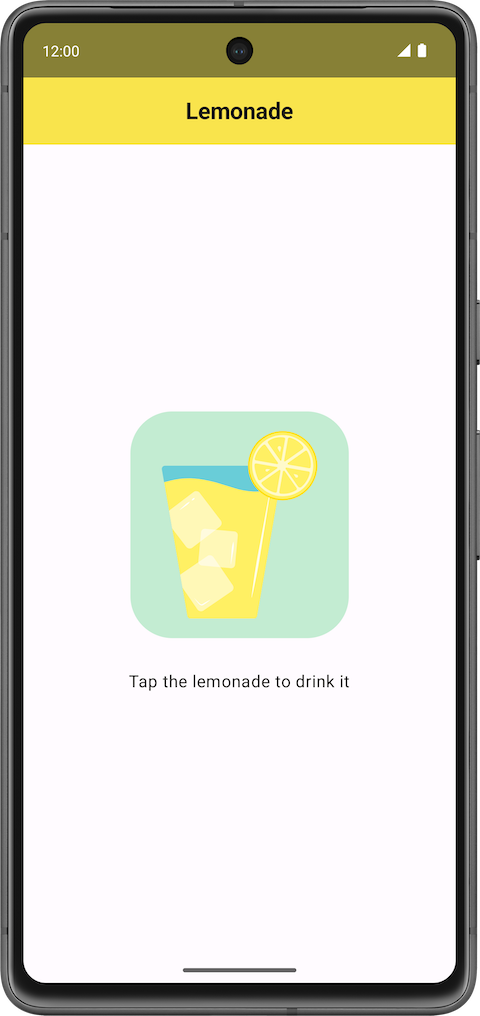

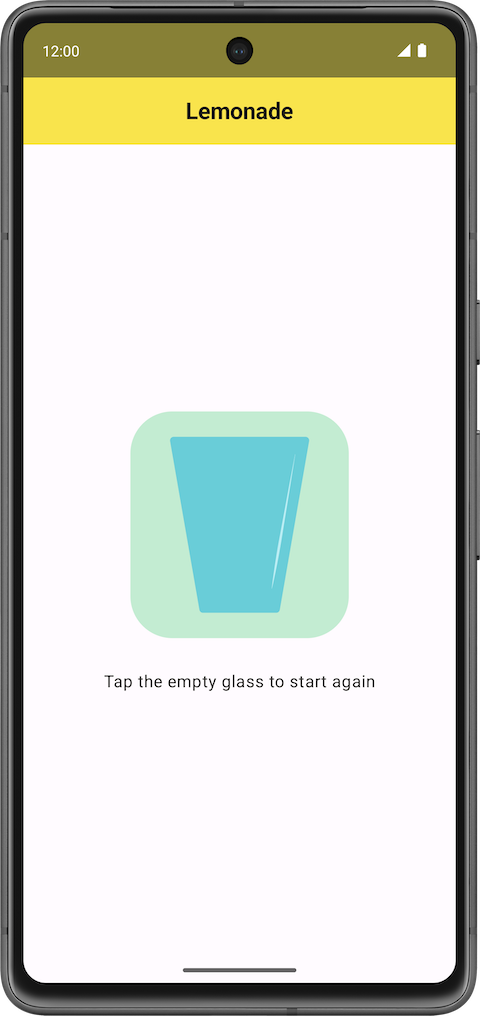

Dice Roller app¶

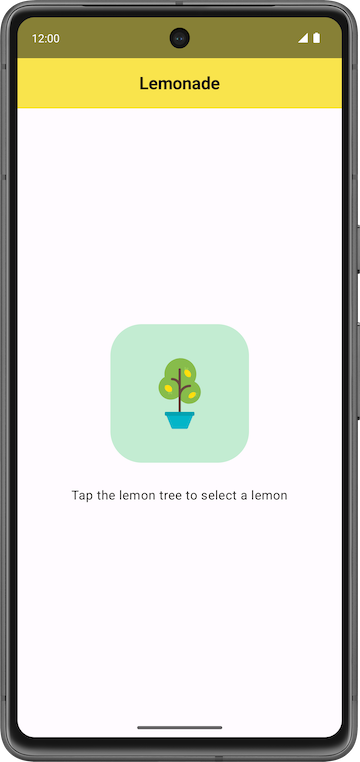

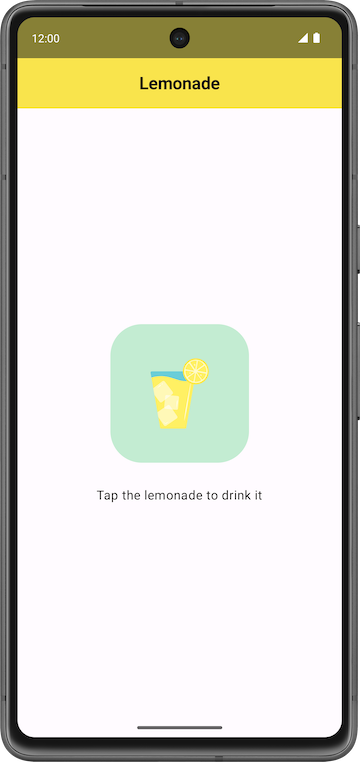

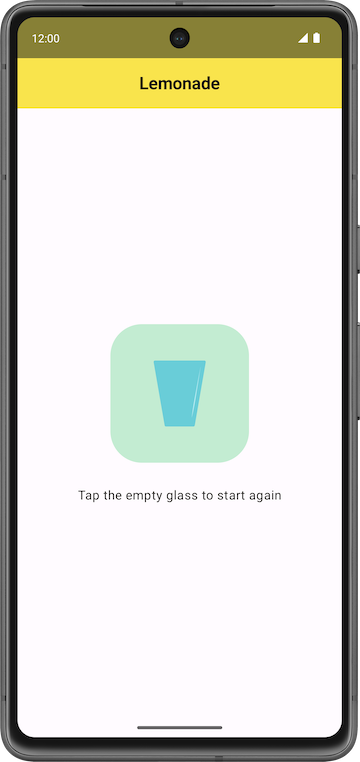

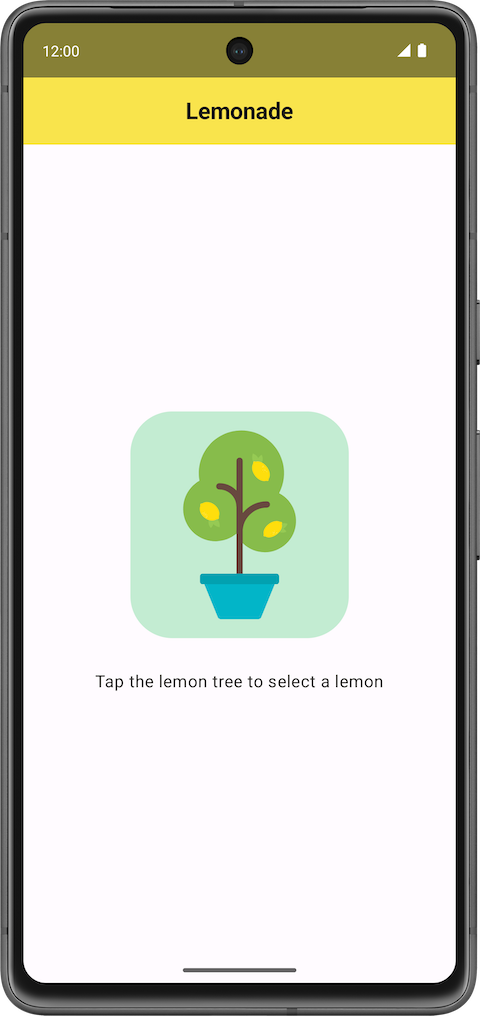

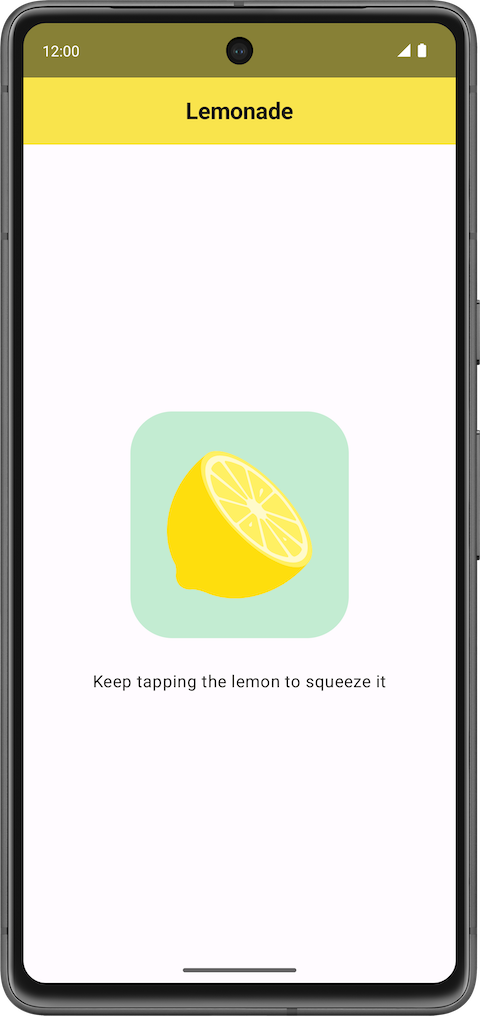

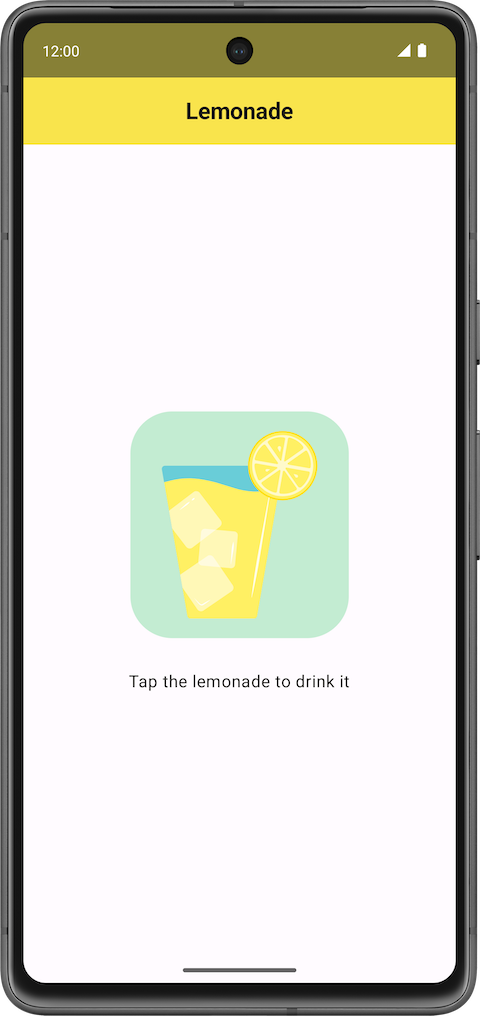

The Dice Roller app lets users tap a

Buttoncomposable to roll a dice. The outcome of the roll is shown with anImagecomposable on the screen.The app:

Solution code: Dice Roller¶

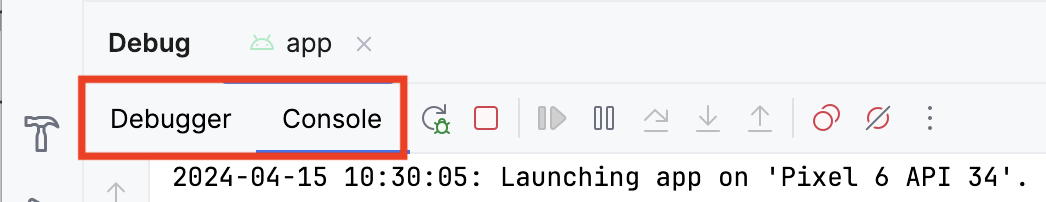

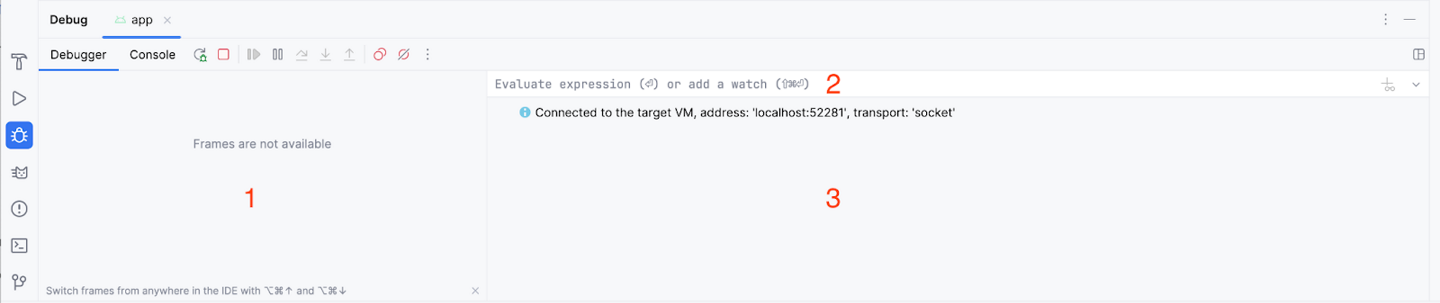

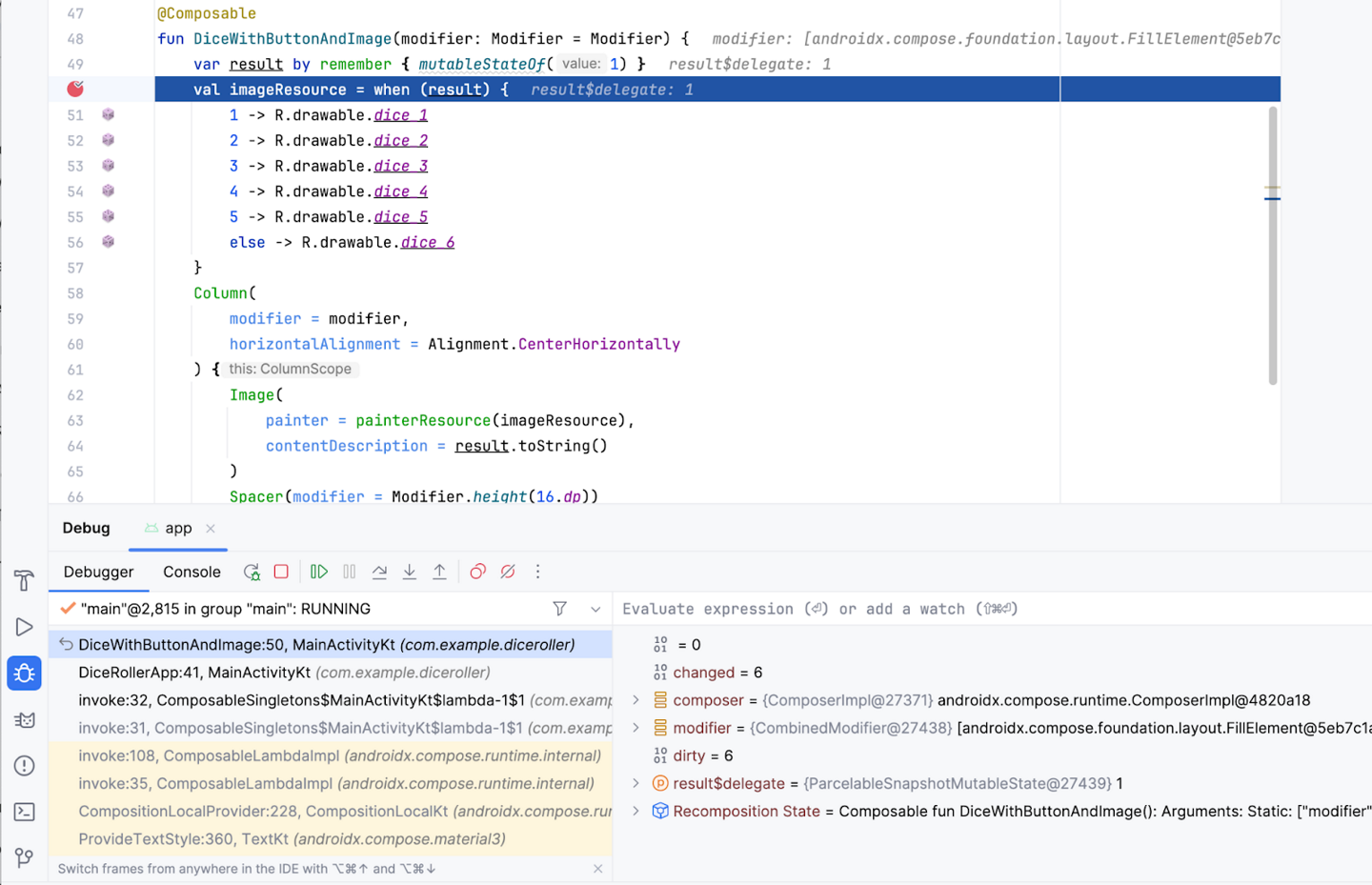

We’ll start with the solution code, and walk through it to learn how it works.

Branch: main

Clone:

$ git clone https://github.com/google-developer-training/basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-dice-roller.git

In

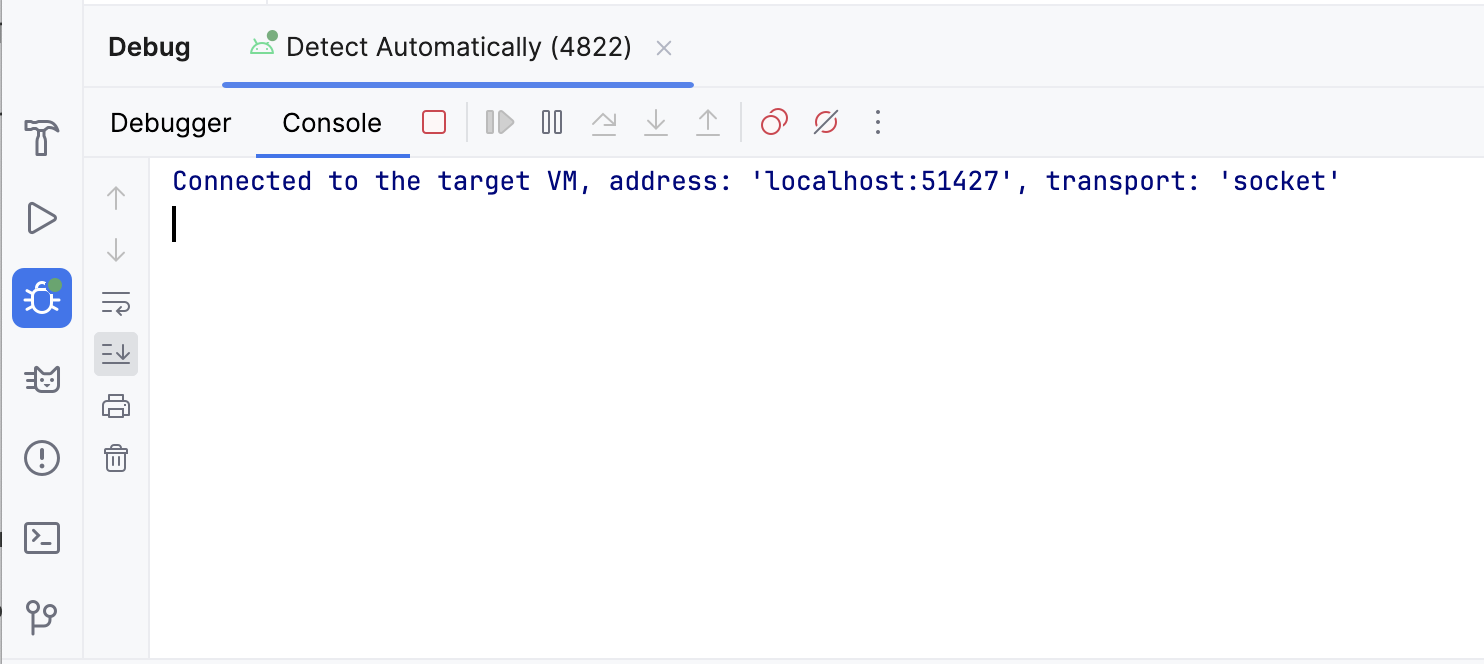

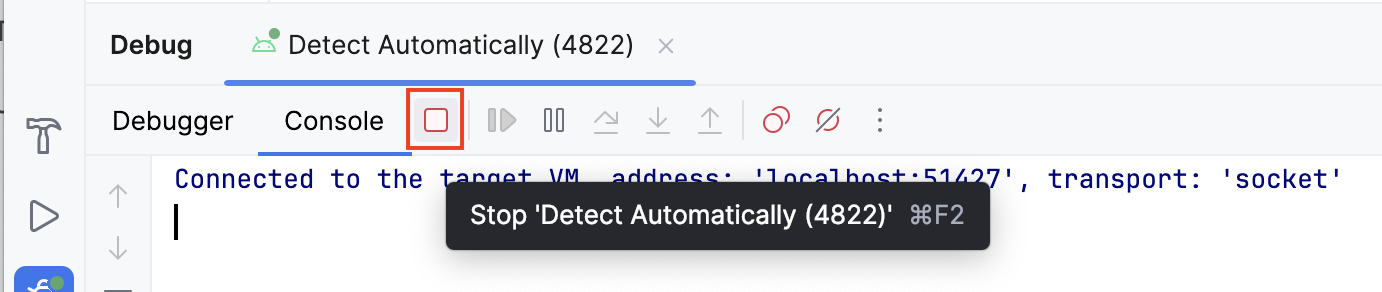

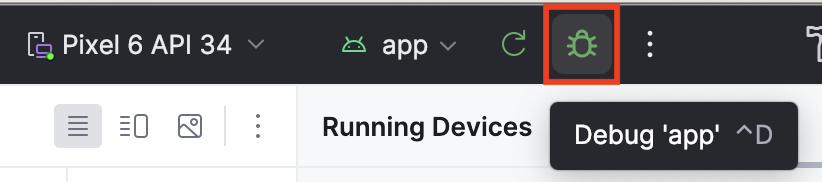

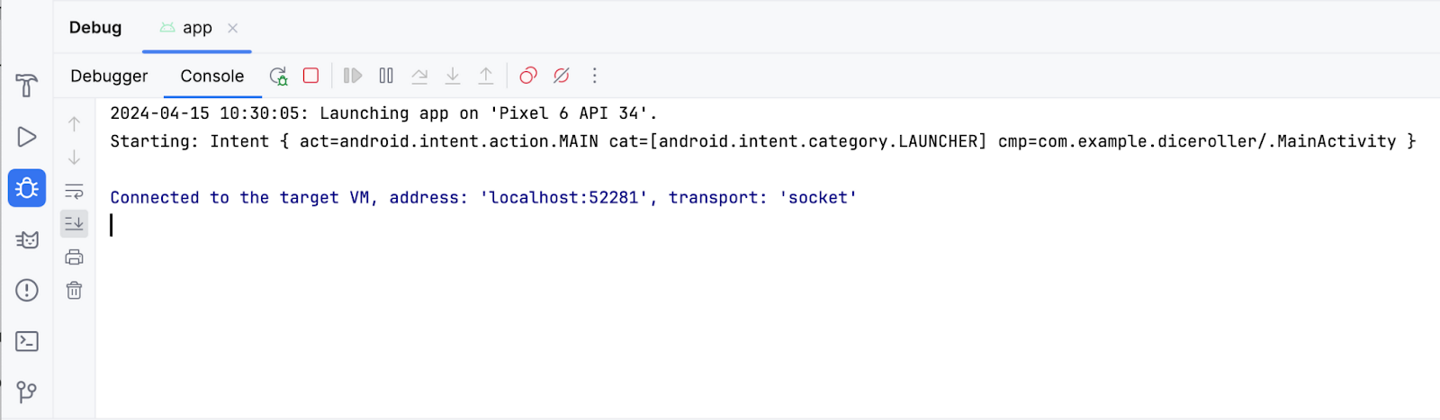

MainActivity.kt:class MainActivity : ComponentActivity() { override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState) setContent { DiceRollerTheme { Surface( modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize(), color = MaterialTheme.colorScheme.background ) { DiceRollerApp() } } } } } @Preview @Composable fun DiceRollerApp() { DiceWithButtonAndImage(modifier = Modifier .fillMaxSize() .wrapContentSize(Alignment.Center) ) } @Composable fun DiceWithButtonAndImage(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { // Result of the dice roll is a mutable state variable, with a default value of 1. // It's delegated to remember so that it retains its value across recompositions. var result by remember { mutableStateOf(1) } // Select the image resource based on the result of the dice roll. val imageResource = when(result) { 1 -> R.drawable.dice_1 2 -> R.drawable.dice_2 3 -> R.drawable.dice_3 4 -> R.drawable.dice_4 5 -> R.drawable.dice_5 else -> R.drawable.dice_6 } // The DiceWithButtonAndImage composable comprises a column that contains an image to show the dice roll, and a button for the user to roll the dice. Column(modifier = modifier, horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { Image(painter = painterResource(imageResource), contentDescription = result.toString()) Button( onClick = { result = (1..6).random() }, // Generate a random number between 1 and 6 when the button is clicked ) { // Text composable to display the button label Text(text = stringResource(R.string.roll), fontSize = 24.sp) } } }

Add a modifier¶

Compose uses a

Modifierobject to decorate or modify the behavior of Compose UI elements. This is used to style the the Dice Roller app’s UI components.The

DiceWithButtonAndImage()composable accepts amodifierparameter, which is of typeModifier. This allows the caller to pass in aModifierobject that can be used to modify the behavior and decoration of the UI components inside theDiceWithButtonAndImage()composable.@Composable fun DiceWithButtonAndImage(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { // ... Column(modifier = modifier, horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { // ... } }

The

modifierparameter has a default value ofModifier. This means that when a caller callsDiceWithButtonAndImage(), the caller can either omit themodifierparameter and use the default value, or the caller can specify anotherModifierobject to decorate or modify the behavior of theDiceWithButtonAndImage()composable.As a best practice, the

modifierparameter is passed on a composable’s first child. In this case, theDiceWithButtonAndImage()'s first child is theColumn()composable. This allows the caller to decorate or modify the behavior of theColumn()composable.Now let’s look at how the

DiceWithButtonAndImage()composable is called from theDiceRollerApp()function:@Preview @Composable fun DiceRollerApp() { DiceWithButtonAndImage(modifier = Modifier .fillMaxSize() .wrapContentSize(Alignment.Center) ) }

Basically,

DiceRollerApp()tellsDiceWithButtonAndImage()to fill the maximum size of the parent container, to wrap the content, and to centering it within the available space.How does this work?

Modifieris the “plain” modifier object.Modifier.fillMaxSize()returns aModifierobject that fills the maximum size of the parent container.Modifier.fillMaxSize().wrapContentSize(Alignment.Center)returns aModifierobject that fills the maximum size of the parent container, and wraps the content, centering it within the available space.

The

wrapContentSize()method specifies that the available space should at least be as large as the components inside of it. However, becausefillMaxSize()is used, if the components inside of the layout are smaller than the available space, anAlignmentobject can be passed towrapContentSize()that specifies how the components should align within the available space.Alignment.Centerspecifies that a component centers both vertically and horizontally.

Create a vertical layout¶

Vertical layouts are created with the

Column()function.The

Column()function is a composable layout that places its children in a vertical sequence. In the expected app design, you can see that the dice image displays vertically above the roll button:

Example code with a vertical layout:

// The DiceWithButtonAndImage composable comprises a column that contains an image to show the dice roll, and a button for the user to roll the dice. Column(modifier = modifier, horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { Image(painter = painterResource(imageResource), contentDescription = result.toString()) Button( onClick = { result = (1..6).random() }, // Generate a random number between 1 and 6 when the button is clicked ) { // Text composable to display the button label Text(text = stringResource(R.string.roll), fontSize = 24.sp) } }

imports

import import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.Column

The

modifierargument fromDiceWithButtonAndImage()is passed on to theColumn(). This ensures that the composables inColumn()adhere to any modifier constraints imposed.horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontallyensures that the children within the column are centered horizontally on the device screen.

Add an image¶

The dice image displays the result when the user taps the Roll button. An image is added using the

Imagecomposable, and an image resource.

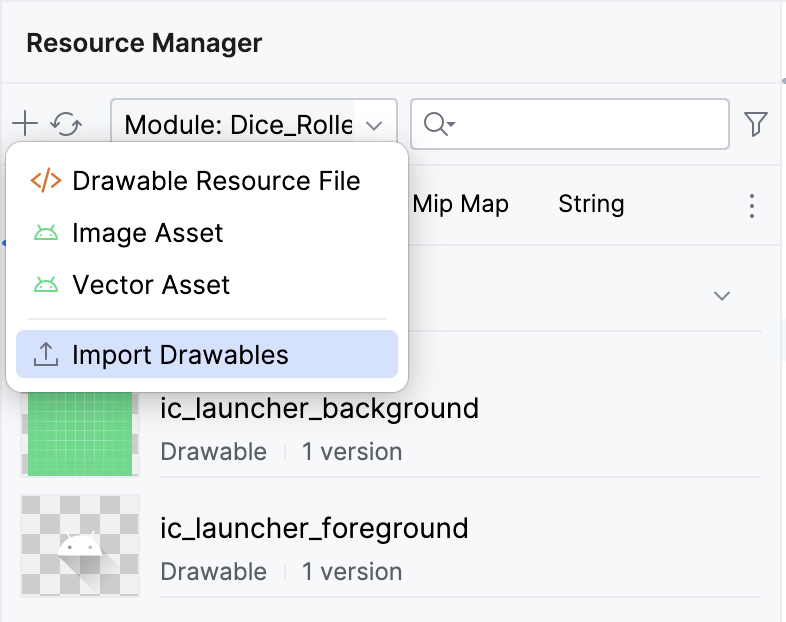

Import Drawables¶

For this app, the dice images are downloaded from dice_images.zip and stored in a dice_images folder. This folder contains six dice image files with dice values from 1 to 6.

Here are the steps to import the dice images. You don’t have to do these, it’s already done, but you can follow the steps in future if you need to import your own images.

Click View ➜ Tool Windows ➜ Resource Manager ➜ + ➜ Import Drawables.

Find and select the dice_images folder, and upload them. The uploaded images will appear like this:

Click Next ➜ Import. The images should appear in the Resource Manager pane.

The images can then be referred using their resource IDs:

R.drawable.dice_1R.drawable.dice_2R.drawable.dice_3R.drawable.dice_4R.drawable.dice_5R.drawable.dice_6

Add an Image composable¶

The

Image()composable is used to display the dice image:// Select the image resource based on the result of the dice roll. val imageResource = when(result) { 1 -> R.drawable.dice_1 2 -> R.drawable.dice_2 3 -> R.drawable.dice_3 4 -> R.drawable.dice_4 5 -> R.drawable.dice_5 else -> R.drawable.dice_6 } // The DiceWithButtonAndImage composable comprises a column that contains an image to show the dice roll, and a button for the user to roll the dice. Column(modifier = modifier, horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { Image(painter = painterResource(imageResource), contentDescription = result.toString()) Button( onClick = { result = (1..6).random() }, // Generate a random number between 1 and 6 when the button is clicked ) { // Text composable to display the button label Text(text = stringResource(R.string.roll), fontSize = 24.sp) } }

imports

import androidx.compose.foundation.Image import androidx.compose.ui.res.painterResource

The

painterResource()function is used to load the image resource. Note the use ofpainterResource(imageResource)to access the drawable resource id:R.drawable.dice_1,R.drawable.dice_2, etc.Composables inside of a

Columncomposable will be stacked vertically. In this case, the Image is stacked on top of th button.Any time you create an Image in your app, you should provide what is called a “content description.” Content descriptions attach descriptions to their respective UI components to increase accessibility. For more information about content descriptions, see Describe each UI element. The

Imagecomposable has acontentDescriptionparameter that accepts a string. This string is used to describe the image to users with visual impairments, and it is read by screen readers.

Add a Spacer¶

A

Spacercomposable is used to add space between 2 other composables. Example:Spacer(modifier = Modifier.height(16.dp))

imports

import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.height import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.Spacer import androidx.compose.ui.unit.dp

Typically, dp dimensions are changed in increments of

4.dp.

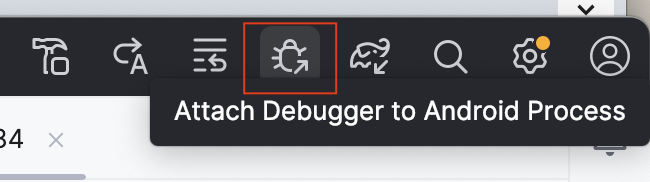

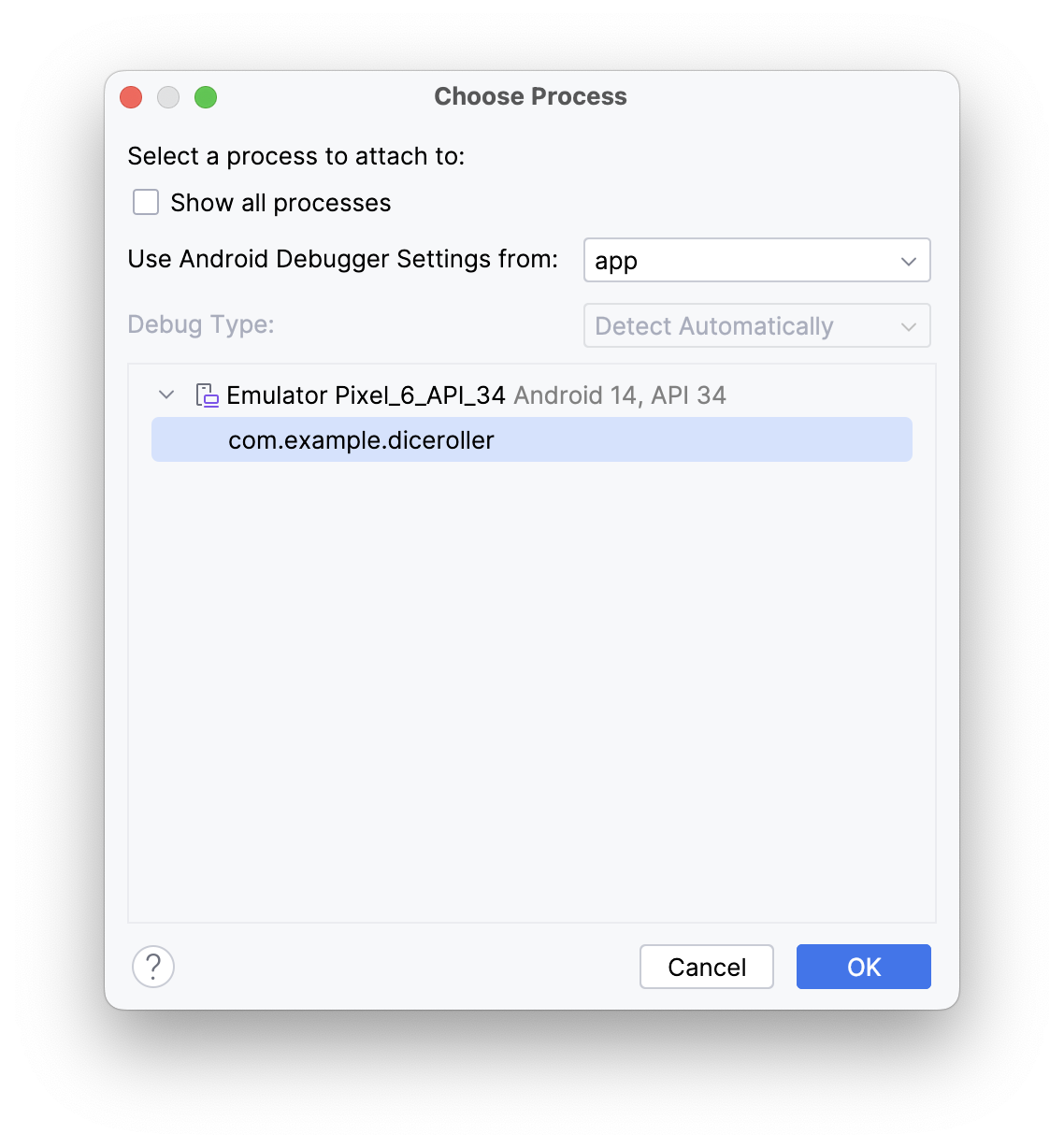

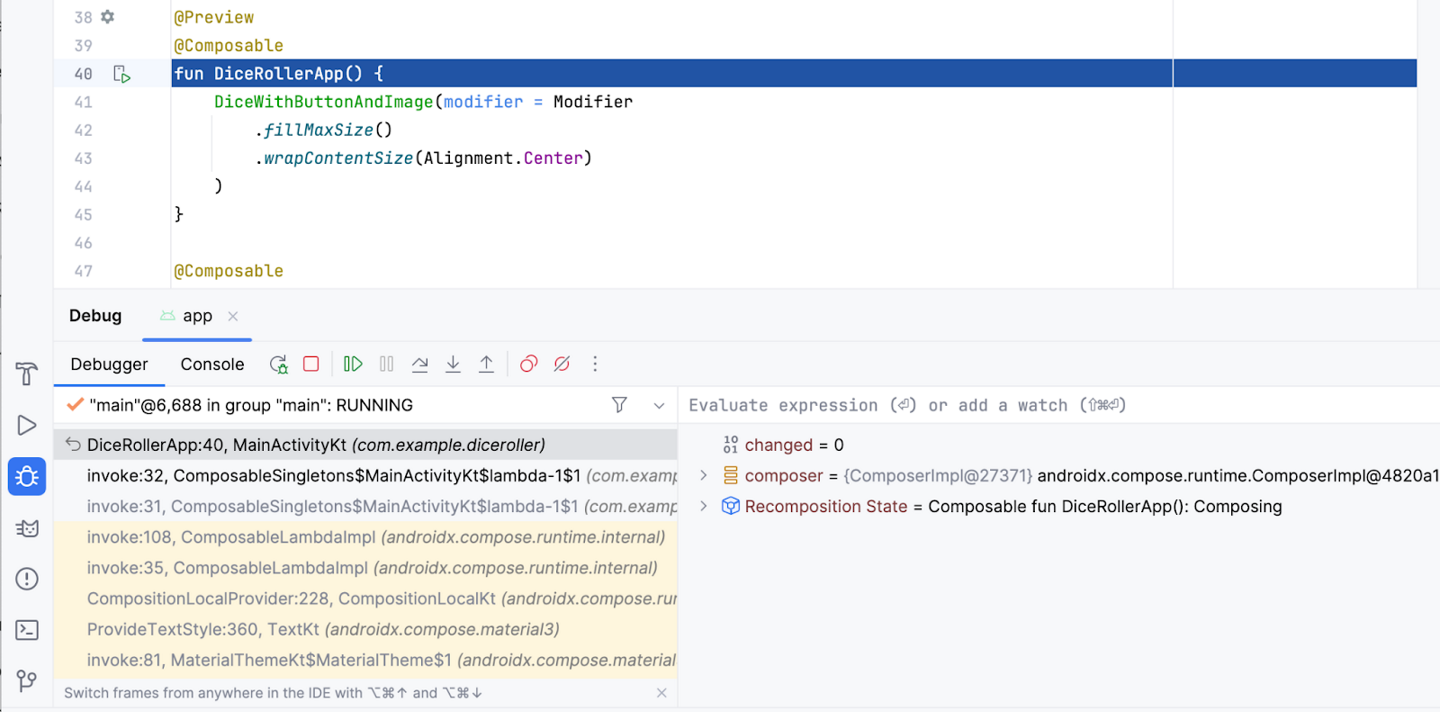

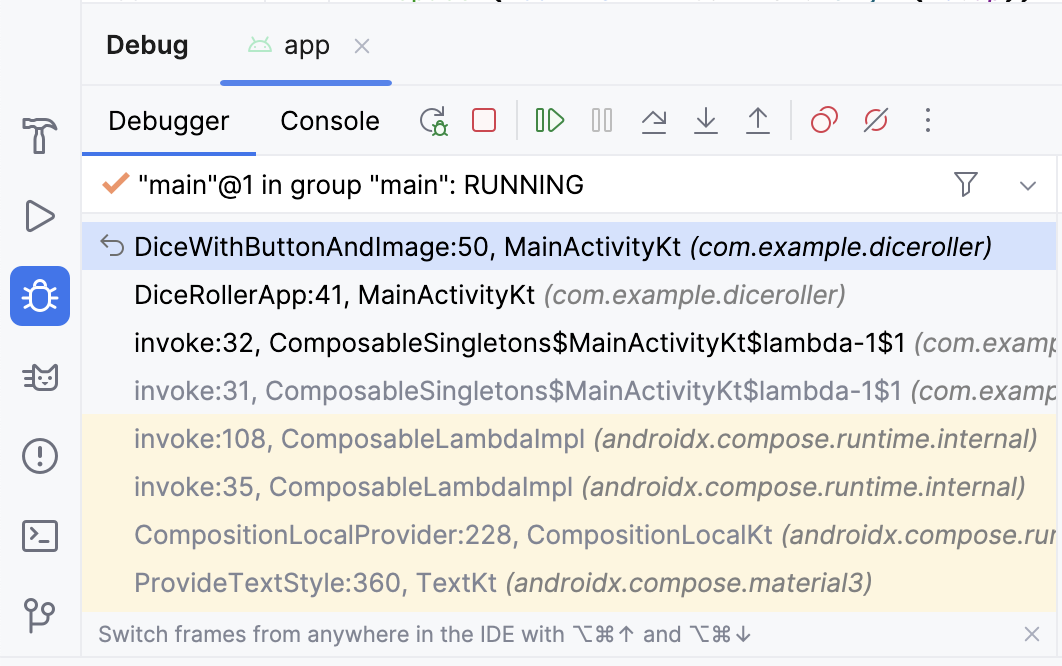

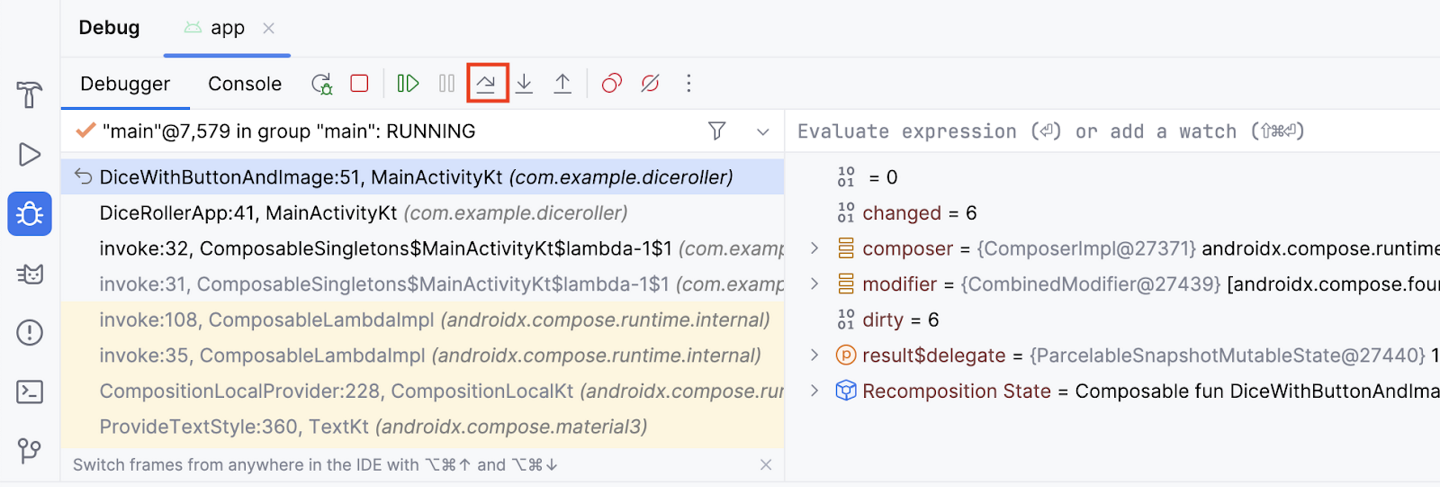

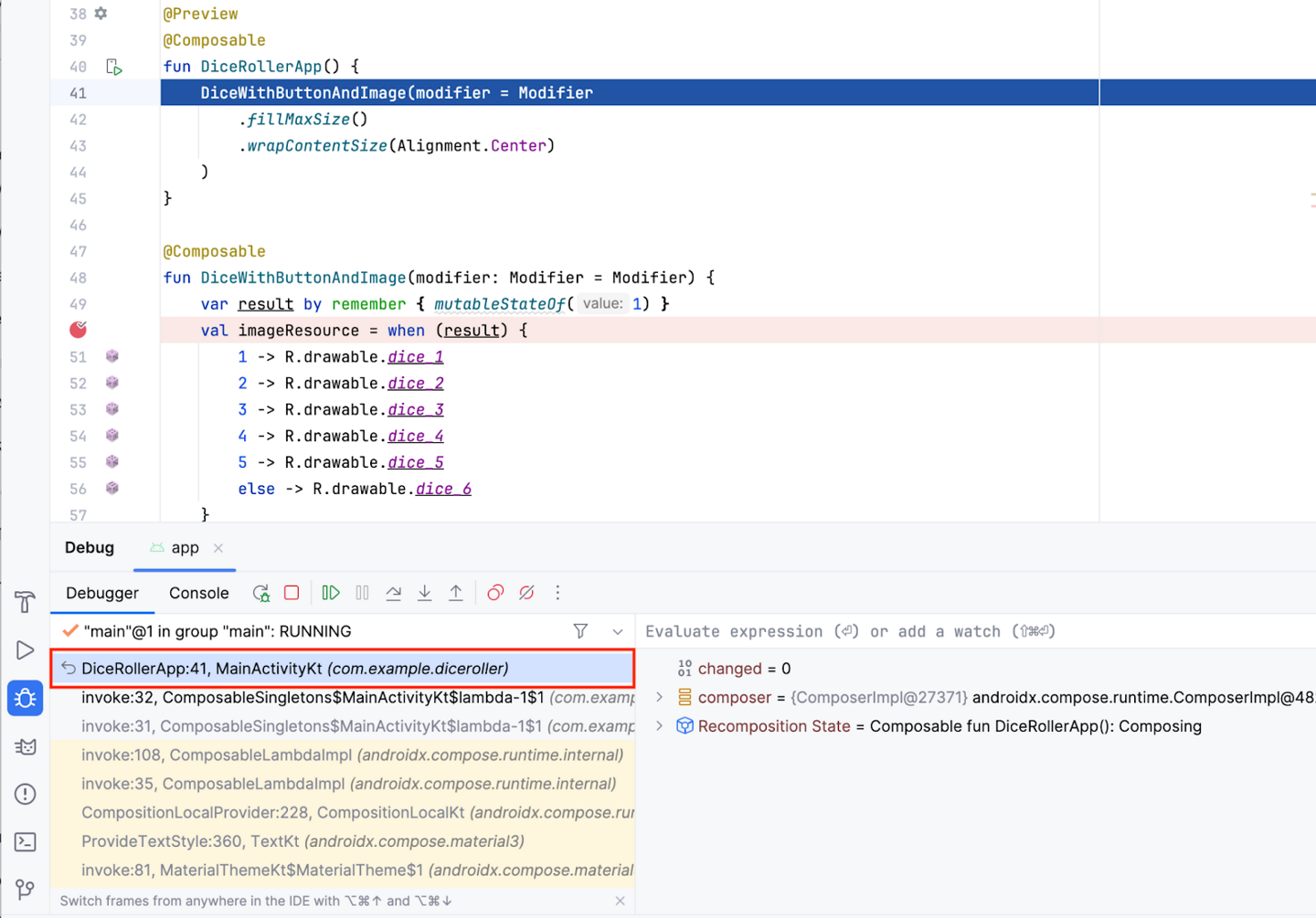

Build the dice roll logic¶

When the button is clicked, the app should perform some action. The

onClickparameter of theButton()composable is used to specify the action.In this case, the action is to generate a random number between 1 and 6: