Week 9: Connect to the Internet¶

Coroutines¶

Concurrency involves performing multiple tasks in your app at the same time. For example, your app can get data from a web server or save user data on the device, while responding to user input events and updating the UI accordingly. Concurrency is a critical skill for Android developers to understand in order to deliver a great user experience.

To do work concurrently in your app, you will be using coroutines. Coroutines allow the execution of a block of code to be suspended and then resumed later, so that other work can be done in the meantime. Coroutines make it easier to write asynchronous code, which means one task doesn’t need to finish completely before starting the next task, enabling multiple tasks to run concurrently.

This codelab walks you through some basic examples in the Kotlin Playground, where you get hands-on practice with coroutines to become more comfortable with asynchronous programming.

Synchronous code¶

Simple Program¶

In synchronous code, only one conceptual task is in progress at a time. You can think of it as a sequential linear path. One task must finish completely before the next one is started. Below is an example of synchronous code.

Open Kotlin Playground.

Replace the code with the following code for a program that shows a weather forecast of sunny weather. In the

main()function, first we print out the text:Weather forecast. Then we print out:Sunny.fun main() { println("Weather forecast") println("Sunny") }

The output:

Weather forecast Sunny

println()is a synchronous call: the task of printing the text to the output is completed before execution can move to the next line of code. Because each function call inmain()is synchronous, the entiremain()function is synchronous. Whether a function is synchronous or asynchronous is determined by the parts that it’s composed of.A synchronous function returns only when its task is fully complete. So after the last print statement in

main()is executed, all work is done. Themain()function returns and the program ends.

Add a delay¶

Now let’s pretend that getting the weather forecast of sunny weather requires a network request to a remote web server. Simulate the network request by adding a delay in the code before printing that the weather forecast is sunny.

Modify your code to add

delay(1000), which delays execution of the remainder of themain()function by 1000 milliseconds, or 1 second. Don’t run the code yet.// Coroutines library needed for delay() import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { println("Weather forecast") delay(1000) println("Sunny") }

delay()is actually a special suspend function provided by the Kotlin coroutines library. Execution ofmain()suspends (pauses), and resumes once the specified duration of the delay is over (one second in this case).Running the code produces a compile error:

Suspend function 'delay' should be called only from a coroutine or another suspend function

For the purposes of learning coroutines within the Kotlin Playground, you can wrap your existing code with a call to the

runBlocking()function from the coroutines library.runBlocking()runs an event loop, which can handle multiple tasks at once by continuing each task where it left off when it’s ready to be resumed.The body of

runBlocking{}is executed in a new coroutine. Use this code:import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") delay(1000) println("Sunny") } }

runBlocking()is synchronous; it will not return until all work within its lambda block is completed. It will wait for the work indelay()to complete first, then continue withprintln("Sunny"). Once all the work in therunBlocking()function is complete, the function returns, which ends the program.Run the program. The output:

Weather forecast Sunny

The output is the same as before. The code is still synchronous - it runs in a straight line and only does one thing at a time. However, the difference now is that it runs over a longer period of time due to the delay.

The “co-” in coroutine means cooperative. The code cooperates to share the underlying event loop. When it needs to wait for something, it suspends, which allows other work to be run in the meantime. (The “-routine” part in “coroutine” means “a set of instructions”, like a function.)

In this example, the coroutine suspends when it reaches the

delay()call. Other work can be done in that one second when the coroutine is suspended (even though in this program, there is no other work to do). Once the duration of the delay elapses, then the coroutine resumes execution and can proceed with printing Sunny to the output.Note

In general, only use

runBlocking()within amain()function like this for learning purposes. In your Android app code, you do not needrunBlocking()because Android provides an event loop for your app to process resumed work when it becomes ready.runBlocking()can be useful in your tests, however, and can let your test await specific conditions in your app before invoking the test assertions.

Suspending functions¶

If the actual logic to perform the network request to get the weather data becomes more complex, you may want to extract that logic out into its own function. Let’s refactor the code to see its effect:

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") printForecast() } } fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") }

Running the program produces the same compile error you saw earlier. A suspend function can only be called from a coroutine or another suspend function, so define

printForecast()as a suspend function:import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") printForecast() } } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") }

delay()is a suspending function. NowprintForecast()is a suspending function too.A suspending function is like a regular function, but it can be suspended and resumed again later. To do this, suspend functions can only be called from other suspend functions.

A suspending function may contain zero or more suspension points. A suspension point is the place within the function where execution of the function can suspend. Once execution resumes, it picks up where it last left off in the code, and proceeds with the rest of the function.

Add another suspending function,

printTemperature():import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") printForecast() } } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") } suspend fun printTemperature() { delay(1000) println("30\u00b0C") // }

You can pretend that this does a network request to get the temperature data for the weather forecast. The escape sequence

"\u00b0"prints the degree symbol°.Call the new

printTemperature()function fromrunBlocking():import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") printForecast() printTemperature() } } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") } suspend fun printTemperature() { delay(1000) println("30\u00b0C") }

The output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C

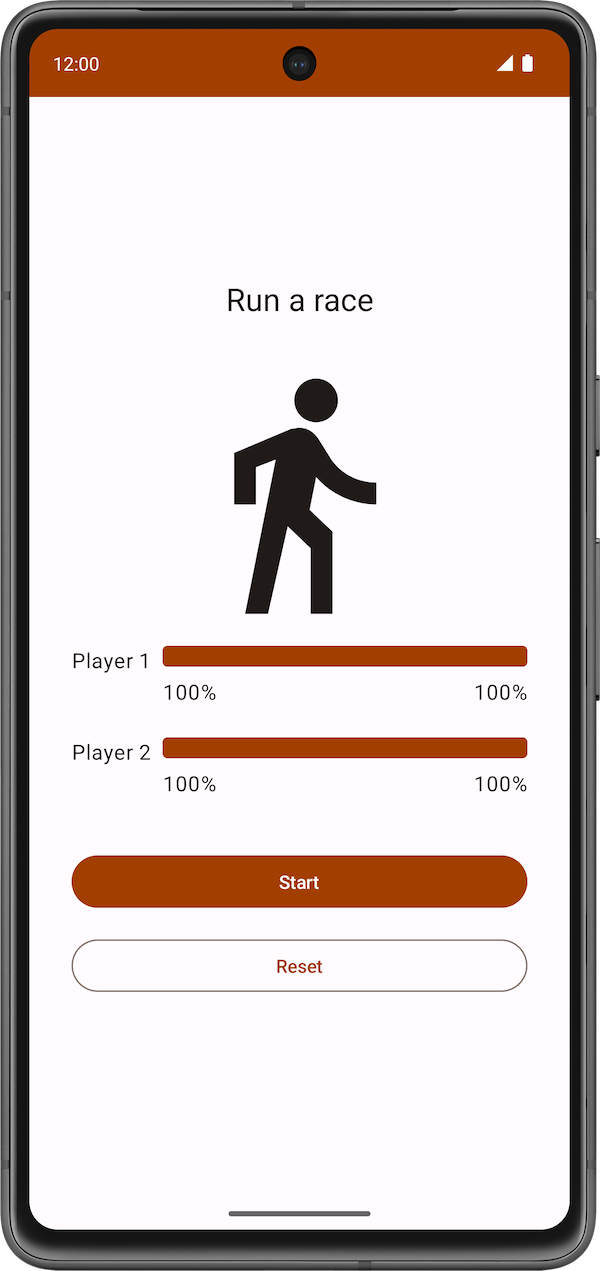

What happens within

runBlocking()?First,

printForecast()gets called. It suspends for 1000ms, resumes, and printsSunny. TheprintForecast()function then returns back to the caller.Next,

printTemperature()gets called. It suspends when it reachesdelay(1000), resumes one second later, and prints the temperature value to the output. SinceprintTemperature()has completed all work, it returns.In the

runBlocking()body, there are no further tasks to execute, so therunBlocking()function returns, and the program ends.

runBlocking()is synchronous and each call in the body will be called sequentially. Note that a well-designed suspending function returns only once all work has been completed. As a result, these suspending functions run one after another.To see how long it takes to execute this program, wrap the code in a call to

measureTimeMillis(), which will return the time it in milliseconds that it takes to run the code. Print out the execution time and divide by 1000.0 to convert milliseconds to seconds.import kotlin.system.* import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { val time = measureTimeMillis { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") printForecast() printTemperature() } } println("Execution time: ${time / 1000.0} seconds") } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") } suspend fun printTemperature() { delay(1000) println("30\u00b0C") }

Output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Execution time: 2.128 seconds

It takes ≈2 seconds to execute. That seems reasonable because each of the suspending functions has a one-second delay.

So far, you’ve seen that the code in a coroutine is invoked sequentially by default. You have to be explicit if you want things to run concurrently, and you will learn how to do that in the next section. You will make use of the cooperative event loop to perform multiple tasks at the same time, which will speed up the execution time of the program.

Asynchronous code¶

launch()¶

The

launch()function launches a new coroutine. To execute tasks concurrently, use multiplelaunch()functions, so that multiple coroutines can execute concurrently, appearing to run at the same time.Coroutines in Kotlin follow a key concept called structured concurrency, where code is sequential by default, and cooperates with an underlying event loop, unless you explicitly ask for concurrent execution (e.g. using

launch()).The assumption is that if you call a function, it should finish its work completely by the time it returns, regardless of how many coroutines it may have used in its implementation details. Even if it fails with an exception, once the exception is thrown, there are no more pending tasks from the function. Hence, all work is finished once control flow returns from the function, whether it threw an exception or completed its work successfully.

Run this code, notice the use of

launch:import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") launch { printForecast() } launch { printTemperature() } } } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") } suspend fun printTemperature() { delay(1000) println("30\u00b0C") }

Run the program. Here’s the output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C

The output is the same, but the program completes faster. Previously, you had to wait for

printForecast()to finish completely before moving on toprintTemperature(). NowprintForecast()andprintTemperature()can run concurrently because they are in separate coroutines.

The call to

launch { printForecast() }can return before all the work inprintForecast()is completed. That is the beauty of coroutines. You can move onto the nextlaunch()call to start the next coroutine. Similarly, thelaunch { printTemperature() }also returns even before all work is completed.To see how much faster the program is now, add

measureTimeMillis():import kotlin.system.* import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { val time = measureTimeMillis { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") launch { printForecast() } launch { printTemperature() } } } println("Execution time: ${time / 1000.0} seconds") } suspend fun printForecast() { delay(1000) println("Sunny") } suspend fun printTemperature() { delay(1000) println("30\u00b0C") }

Output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Execution time: 1.122 seconds

The execution time has gone down from ≈2 s to ≈1 s, so it’s faster to execute the program once you add concurrent operations! You can remove this time measurement code before moving on.

Modify the

runBlocking()code to add an additionalprintln():... fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") launch { printForecast() } launch { printTemperature() } println("kthxbye") } } ...

The output:

Weather forecast kthxbye Sunny 30°C

After the two coroutines for

printForecast()andprintTemperature()are launched, the next instruction printskthxbyeimmediately. This demonstrates the “fire and forget” nature oflaunch(). You fire off a new coroutine withlaunch(), and don’t have to worry about when its work is finished.Later the coroutines will complete their work, and print the remaining output statements. Once all the work (including all coroutines) in the body of the

runBlocking()call have been completed, thenrunBlocking()returns and the program ends.Now you’ve changed your synchronous code into asynchronous code. When an asynchronous function returns, the task may not be finished yet. This is what you saw in the case of

launch(). The function returned, but its work was not completed yet. By usinglaunch(), multiple tasks can run concurrently in your code, which is a powerful capability to use in the Android apps you develop.

async()¶

In the real world, you won’t know how long the network requests for forecast and temperature will take. If you want to display a unified weather report when both tasks are done, then the current approach with

launch()isn’t sufficient. That’s whereasync()comes in.Use

async()if you care about when the coroutine finishes, and need a return value from it.async()returns aDeferredobject, which is like a promise that the result will be in there when it’s ready. You can access the result on theDeferredobject usingawait().Use this code, notice the

async()calls:import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") val forecast: Deferred<String> = async { getForecast() } val temperature: Deferred<String> = async { getTemperature() } // Using await() here makes the code wait until the values of forecast and temperature are available println("${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}") println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(1000) return "30\u00b0C" }

After the two

async()calls, you can access the result of those coroutines by callingawait()on theDeferredobjects.Run the program. The output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C kthxbye

Neat! You created two coroutines that ran concurrently to get the forecast and temperature data. When they each completed, they returned a value. Then you combined the two return values into a single print statement:

Sunny 30°C.

Parallel Decomposition¶

We can take this weather example a step further and see how coroutines can be useful in parallel decomposition of work. Parallel decomposition involves taking a problem and breaking it into smaller subtasks that can be solved in parallel. When the results of the subtasks are ready, you can combine them into a final result.

Run this code:

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") println(getWeatherReport()) println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { getTemperature() } // No need return keyword here, the last expression in a lambda block is returned "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(1000) return "30\u00b0C" }

Note

Another way of writing

getWeatherReport()issuspend fun getWeatherReport(): String { return coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { getTemperature() } // No need return keyword here, the last expression in a lambda block is returned "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" } }

coroutineScope()creates a local scope for this weather report task. The coroutines launched within this scope are grouped together within this scope, which has implications for cancellation and exceptions that you’ll learn about soon.

The output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C kthxbye

The output is the same, but there are some noteworthy takeaways here. First,

coroutineScope()will only return once all its work, including any coroutines it launched, have completed. In this case, both coroutinesgetForecast()andgetTemperature()need to finish and return their respective results. Then theSunnytext and30°Care combined and returned from the scope. TheSunny 30°Cgets printed to the output, and the caller can proceed to the last print statement ofkthxbye.With

coroutineScope(), even though the function is internally doing work concurrently, it appears to the caller as a synchronous operation becausecoroutineScopewon’t return until all work is done. From the POV of the caller, whethercoroutineScope()is synchronous or not, doesn’t matter. It’s just an “implementation detail” that the caller doesn’t need to know about. Analogy: when ordering a Big Mac Meal, you don’t need to know whether the fries, burger, and drink are prepared sequentially by 1 person, or in parallel by 3 people. All you know is after everything is prepared, you get your meal.The key insight here for structured concurrency is that you can take multiple concurrent operations and put it into a single synchronous operation, where concurrency is an “implementation detail”. The only requirement on the calling code is to be in a suspend function or coroutine. Other than that, the structure of the calling code doesn’t need to take into account the concurrency details.

Exceptions and cancellation¶

There are some situations where an error may occur, or some work may be cancelled.

Introduction to exceptions¶

An exception is an unexpected event that happens during execution of your code. You should implement appropriate ways of handling these exceptions, to prevent your app from crashing and impacting the user experience negatively.

Here’s an example of a program that terminates early with an exception. The program is intended to calculate the number of pizzas each person gets to eat, by dividing

numberOfPizzas / numberOfPeople. Say you accidentally forget to set the value of thenumberOfPeopleto an actual value.fun main() { val numberOfPeople = 0 val numberOfPizzas = 20 println("Slices per person: ${numberOfPizzas / numberOfPeople}") }

When you run the program, it will crash with an arithmetic exception because you can’t divide a number by zero.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArithmeticException: / by zero at FileKt.main (File.kt:4) at FileKt.main (File.kt:-1) at jdk.internal.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl.invoke0 (:-2)

This issue has a straightforward fix, where you can change the initial value of

numberOfPeopleto a non-zero number. However, as your code gets more complex, there are certain cases where you can’t anticipate and prevent all exceptions from happening.What happens when one of your coroutines fails with an exception? Modify the code from the weather program to find out.

Exceptions with coroutines¶

Use this code. Note the exception thrown in the

getTemperature()function.import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") println(getWeatherReport()) println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { getTemperature() } "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(500) throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid") return "30\u00b0C" }

The exception simulates that 500 ms after fetching data from the server, an unexpected error happened.

The output:

Weather forecast Exception in thread "main" java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid at FileKt.getTemperature (File.kt:24) at FileKt$getTemperature$1.invokeSuspend (File.kt:-1) at kotlin.coroutines.jvm.internal.BaseContinuationImpl.resumeWith (ContinuationImpl.kt:33)

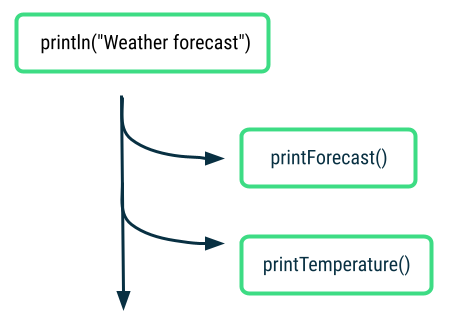

To understand this behavior, you’ll need to know that there is a parent-child relationship among coroutines. You can launch a coroutine (known as the child) from another coroutine (parent). As you launch more coroutines from those coroutines, you can build up a whole hierarchy of coroutines.

The coroutine executing

getTemperature()and the coroutine executinggetForecast()are child coroutines of the same parent coroutine. The behavior you’re seeing with exceptions in coroutines is due to structured concurrency. When one of the child coroutines fails with an exception, it gets propagated upwards. The parent coroutine is cancelled, which in turn cancels any other child coroutines (e.g. the coroutine runninggetForecast()in this case). Lastly, the error gets propagated upwards and the program crashes with theAssertionError.

Try-catch exceptions¶

If you know that certain parts of your code can possibly throw an exception, then you can surround that code with a try-catch block. You can catch the exception and handle it more gracefully in your app, such as by showing the user a helpful error message. Here’s a code snippet of how it might look:

try { // Some code that may throw an exception } catch (e: IllegalArgumentException) { // Handle exception }

This approach also works for asynchronous code with coroutines. You can still use a try-catch expression to catch and handle exceptions in coroutines. The reason is because with structured concurrency, the sequential code is still synchronous code so the try-catch block will still work in the same expected way.

... fun main() { runBlocking { ... try { ... throw IllegalArgumentException("No city selected") ... } catch (e: IllegalArgumentException) { println("Caught exception $e") // Handle error } } } ...

Here’s example code with a try-catch block. It prints the error that is caught, and a message that the weather report is not available.

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") try { println(getWeatherReport()) } catch (e: AssertionError) { println("Caught exception in runBlocking(): $e") println("Report unavailable at this time") } println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { getTemperature() } "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(500) throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid") return "30\u00b0C" }

Run the program. Now the error is handled gracefully, and the program can finish executing successfully.

Weather forecast Caught exception in runBlocking(): java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid Report unavailable at this time kthxbye

If there’s a failure with getting the temperature, then there will be no weather report at all, even if a valid forecast was retrieved.

Here’s an alternative way where the weather report can still print the forecast, even if the temperature failed:

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") println(getWeatherReport()) println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { try { getTemperature() } catch (e: AssertionError) { println("Caught exception $e") // No need return keyword here, the last expression in a lambda block is returned "(No temperature found)" } } // No need return keyword here, the last expression in a lambda block is returned "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(500) throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid") return "30\u00b0C" }

Run the program.

Weather forecast Caught exception java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid Sunny (No temperature found) kthxbye

Calling

getTemperature()failed with an exception, but the code withinasync()was able to catch that exception and handle it gracefully by having the coroutine still return a String that says the temperature was not found. The weather report is still able to be printed, with a successful forecast of Sunny. The temperature is missing in the weather report, but in its place, there is a message explaining that the temperature was not found. This is a better user experience than the program crashing with the error.A helpful way to think about this error handling approach is that

async()is the producer when a coroutine is started with it.await()is the consumer because it’s waiting to consume the result from the coroutine. The producer does the work and produces a result. The consumer consumes the result. If there’s an exception in the producer, then the consumer will get that exception if it’s not handled, and the coroutine will fail. However, if the producer is able to catch and handle the exception, then the consumer won’t see that exception and will see a valid result.Here’s the

getWeatherReport()code again for reference:suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { try { getTemperature() } catch (e: AssertionError) { println("Caught exception $e") "(No temperature found)" } } // No need return keyword here, the last expression in a lambda block is returned "${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}" }

In this case, the producer

async()was able to catch and handle the exception and still return(No temperature found). The consumerawait()receives thisStringresult and doesn’t even need to know that an exception happened. This is another option to gracefully handle an exception that you expect could happen in your code.Note

Exceptions are propagated differently for coroutines started with

launch()versusasync(). Within a coroutine started bylaunch(), an exception is thrown immediately so you can surround code with a try-catch block if it’s expected to throw an exception. See example.Warning

Within a

try-catchstatement in your coroutine code, avoid catching a generalExceptionbecause that includes a very broad range of exceptions. You could be inadvertently catching and suppressing an error that is actually a bug that should be fixed in your code. Another important reason is that cancellation of coroutines, which is discussed later in this section, depends onCancellationException. So if you catch any type ofExceptionincludingCancellationExceptionwithout rethrowing them, then the cancellation behavior within your coroutines may behave differently than expected. Instead, catch a specific type of exception that you expect may be thrown from your code.Exceptions propagate upwards in the tree of coroutines, unless they are handled. It’s also important to be careful when the exception propagates all the way to the root of the hierarchy, which could crash your whole app.

Learn more details about exception handling in the Exceptions in coroutines blogpost and Coroutine exceptions handling article.

Cancellation¶

A similar topic to exceptions is cancellation of coroutines. This scenario is typically user-driven when an event has caused the app to cancel work that it had previously started.

Example:

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("Weather forecast") println(getWeatherReport()) println("kthxbye") } } suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope { val forecast = async { getForecast() } val temperature = async { getTemperature() } delay(200) temperature.cancel() "${forecast.await()}" } suspend fun getForecast(): String { delay(1000) return "Sunny" } suspend fun getTemperature(): String { delay(1000) return "30\u00b0C" }

Output:

Weather forecast Sunny kthxbye

The weather report only consists of the weather forecast

Sunny, but not the temperature because that coroutine was cancelled.A coroutine can be cancelled, but it won’t affect other coroutines in the same scope and the parent coroutine will not be cancelled.

Note

You can learn more about Cancellation of Coroutines in this Android Developers blogpost. Cancellation must be cooperative, so you should implement your coroutine so that it can be cancelled.

In this section, you saw how cancellation and exceptions behave in coroutines and how that’s tied to the coroutine hierarchy. Let’s learn more of the formal concepts behind coroutines, so that you can understand how all the important pieces come together.

Coroutine concepts¶

When executing work asynchronously or concurrently, some questions arise: how will the work be executed? How long should the coroutine exist? What should happen if it gets cancelled or fails with an error?

Coroutines follow the principle of structured concurrency, which forces you to answer these questions when you use coroutines in your code using a combination of mechanisms.

Job¶

When you launch a coroutine with the

launch()function, it returns an instance ofJob. TheJobholds a reference to the coroutine, so you can manage its lifecycle.val job = launch { ... }

Note

The

Deferredobject that is returned from a coroutine started with theasync()function is aJobas well, and it holds the future result of the coroutine.The job can be used to control the life cycle, or how long the coroutine lives for, such as cancelling the coroutine if you don’t need the task anymore.

job.cancel()

With a job, you can check if it’s active, cancelled, or completed. The job is completed if the coroutine and any coroutines that it launched have completed all of their work. Note that the coroutine could have completed due to a different reason, such as being cancelled, or failing with an exception, but the job is still considered completed at that point.

Jobs also keep track of the parent-child relationship among coroutines.

Job hierarchy¶

When a coroutine launches another coroutine, the job that returns from the new coroutine is called the child of the original parent job.

val job = launch { ... val childJob = launch { ... } ... }

These parent-child relationships form a job hierarchy, where each job can launch jobs, and so on.

This parent-child relationship is important because it will dictate certain behavior:

If a parent job gets cancelled, then its child jobs also get cancelled.

When a child job is canceled using

job.cancel(), it terminates, but it does not cancel its parent.If a job fails with an exception, it cancels its parent with that exception. This is known as propagating the error upwards (to the parent, the parent’s parent, and so on).

CoroutineScope¶

Coroutines are typically launched into a

CoroutineScope. This ensures that we don’t have coroutines that are unmanaged and get lost, which could waste resources.launch()andasync()are extension functions onCoroutineScope. Calllaunch()orasync()on the scope to create a new coroutine within that scope.A

CoroutineScopeis tied to a lifecycle, which sets bounds on how long the coroutines within that scope will live. If a scope gets cancelled, then its job is cancelled, and the cancellation of that propagates to its child jobs. If a child job in the scope fails with an exception, then other child jobs get cancelled, the parent job gets cancelled, and the exception gets re-thrown to the caller.

CoroutineScope in Kotlin Playground¶

In this codelab, you used

runBlocking()which provides aCoroutineScopefor your program. You also learned how to usecoroutineScope { }to create a new scope within thegetWeatherReport()function.

CoroutineScope in Android apps¶

Android provides coroutine scope support in entities that have a well-defined lifecycle, such as

Activity(lifecycleScope) andViewModel(viewModelScope). Coroutines that are started within these scopes will adhere to the lifecycle of the corresponding entity, such asActivityorViewModel.For example, say you start a coroutine in an

Activitywith the provided coroutine scope calledlifecycleScope. If the activity gets destroyed, then thelifecycleScopewill get canceled and all its child coroutines will automatically get canceled too. You just need to decide if the coroutine following the lifecycle of theActivityis the behavior you want.In the Race Tracker Android app you will be working on, you’ll learn a way to scope your coroutines to the lifecycle of a composable.

Implementation Details of CoroutineScope¶

CoroutineScopeis declared as an interface, and it contains aCoroutineContextas a variable.The

launch()andasync()functions create a new child coroutine within that scope and the child also inherits the context from the scope. What is contained within the context?

CoroutineContext¶

The

CoroutineContextprovides information about the context in which the coroutine will be running in. TheCoroutineContextis essentially a key ➜ element map that stores elements. Each element has a unique key. These are not required fields, but here are some examples of what may be contained in a context:name - name of the coroutine, uniquely identifies it

job - controls the lifecycle of the coroutine

dispatcher - dispatches the work to the appropriate thread

exception handler - handles exceptions thrown by the code executed in the coroutine

Note

These are default values for the

CoroutineContext, which will be used if you don’t provide values for them:name:

coroutinejob: none

dispatcher:

Dispatchers.Defaultexception handler: none

Each of the elements in a context can be appended together with the

+operator. For example, oneCoroutineContextcould be defined as follows:Job() + Dispatchers.Main + exceptionHandler

If a name is not provided, the default coroutine name is used.

Within a coroutine, if you launch a new coroutine, the child coroutine will inherit the

CoroutineContextfrom the parent coroutine, but replace the job specifically for the coroutine that just got created. You can also override any elements that were inherited from the parent context by passing in arguments to thelaunch()orasync()functions for the parts of the context that you want to be different.scope.launch(Dispatchers.Default) { ... }

You can learn more about

CoroutineContextand how the context gets inherited from the parent in this KotlinConf conference video talk.You’ve seen the mention of dispatcher several times. Its role is to dispatch or assign the work to a thread. Let’s learn about threads and dispatchers in more detail.

Dispatcher¶

Coroutines use dispatchers to determine the thread to use for its execution. A thread can be started, does some work (executes some code), and then terminates when there’s no more work to be done.

When a user starts your app, the Android system creates a new process and a single thread of execution for your app, which is known as the main thread. The main thread handles many important operations for your app including Android system events, drawing the UI on the screen, handling user input events, and more. As a result, most of the code you write for your app will likely run on the main thread.

There are two terms to understand when it comes to the threading behavior of your code: blocking and non-blocking.

A regular function blocks the calling thread until its work is completed. That means it does not yield the calling thread until the work is done, so no other work can be done in the meantime.

Non-blocking code yields the calling thread until a certain condition is met, so you can do other work in the meantime. You can use an asynchronous function to perform non-blocking work because it returns before its work is completed.

In the case of Android apps, you should only call blocking code on the main thread if it will execute fairly quickly. The goal is to keep the main thread unblocked, so that it can execute work immediately if a new event is triggered. This main thread is the UI thread for your activities and is responsible for UI drawing and UI related events. When there’s a change on the screen, the UI needs to be redrawn. For something like an animation on the screen, the UI needs to be redrawn frequently so that it appears like a smooth transition. If the main thread needs to execute a long-running block of work, then the screen won’t update as frequently and the user will see an abrupt transition (known as “jank”) or the app may hang or be slow to respond.

Hence we need to move any long-running work items off the main thread and handle it in a different thread. Your app starts off with a single main thread, but you can choose to create multiple threads to perform additional work. These additional threads can be referred to as worker threads. It’s perfectly fine for a long-running task to block a worker thread for a long time, because in the meantime, the main thread is unblocked and can actively respond to the user.

There are some built-in dispatchers that Kotlin provides:

Dispatchers.Main: Use this dispatcher to run a coroutine on the main Android thread. This dispatcher is used primarily for handling UI updates and interactions, and performing quick work.Dispatchers.IO: This dispatcher is optimized to perform disk or network I/O outside of the main thread. For example, read from or write to files, and execute any network operations.Dispatchers.Default: This is a default dispatcher used when callinglaunch()andasync(), when no dispatcher is specified in their context. You can use this dispatcher to perform computationally-intensive work outside of the main thread. For example, processing a bitmap image file.

Note

There’s also

Executor.asCoroutineDispatcher()andHandler.asCoroutineDispatcher()extensions, if you need to make aCoroutineDispatcherfrom aHandlerorExecutorthat you already have available.Try the following example in Kotlin Playground to better understand coroutine dispatchers.

import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { launch { delay(1000) println("10 results found.") } println("Loading...") } }

Now wrap the contents of the launched coroutine with a call to

withContext()to change theCoroutineContextthat the coroutine is executed within, and specifically override the dispatcher. Switch to using theDispatchers.Default(instead ofDispatchers.Mainwhich is currently being used for the rest of the coroutine code in the program).import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { launch { withContext(Dispatchers.Default) { delay(1000) println("10 results found.") } } println("Loading...") } }

Switching dispatchers is possible because

withContext()is itself a suspending function. It executes the provided block of code using a new CoroutineContext. The new context comes from the context of the parent job (the outerlaunch()block), except it overrides the dispatcher used in the parent context with the one specified here:Dispatchers.Default. This is how we are able to go from executing work withDispatchers.Mainto usingDispatchers.Default.Run the program. The output should be:

Loading... 10 results found.

Add print statements to see what thread you are on by calling

Thread.currentThread().name.import kotlinx.coroutines.* fun main() { runBlocking { println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - runBlocking function") launch { println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - launch function") withContext(Dispatchers.Default) { println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - withContext function") delay(1000) println("10 results found.") } println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - end of launch function") } println("Loading...") } }

Run the program. The output should be:

main @coroutine#1 - runBlocking function Loading... main @coroutine#2 - launch function DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#2 - withContext function 10 results found. main @coroutine#2 - end of launch function

From this output, you can observe that most of the code is executed in coroutines on the main thread. However, for the portion of your code in the

withContext(Dispatchers.Default)block, that is executed in a coroutine on a Default Dispatcher worker thread (which is not the main thread).Notice that after

withContext()returns, the coroutine returns to running on the main thread (as evidenced by output statement:main @coroutine#2 - end of launch function). This example demonstrates that you can switch the dispatcher by modifying the context that is used for the coroutine.If you have coroutines that were started on the main thread, and you want to move certain operations off the main thread, then you can use

withContextto switch the dispatcher being used for that work. Choose appropriately from the available dispatchers:Main,Default, andIOdepending on the type of operation it is. Then that work can be assigned to a thread (or group of threads called a thread pool) designated for that purpose. Coroutines can suspend themselves, and the dispatcher also influences how they resume.Note that when working with popular libraries like Room and Retrofit (in this unit and the next one), you may not have to explicitly switch the dispatcher yourself if the library code already handles doing this work using an alternative coroutine dispatcher like

Dispatchers.IO

Now you’ve got a high-level overview of the important parts of coroutines and the role that

CoroutineScope,CoroutineContext,CoroutineDispatcher, andJobsplay in shaping the lifecycle and behavior of a coroutine.

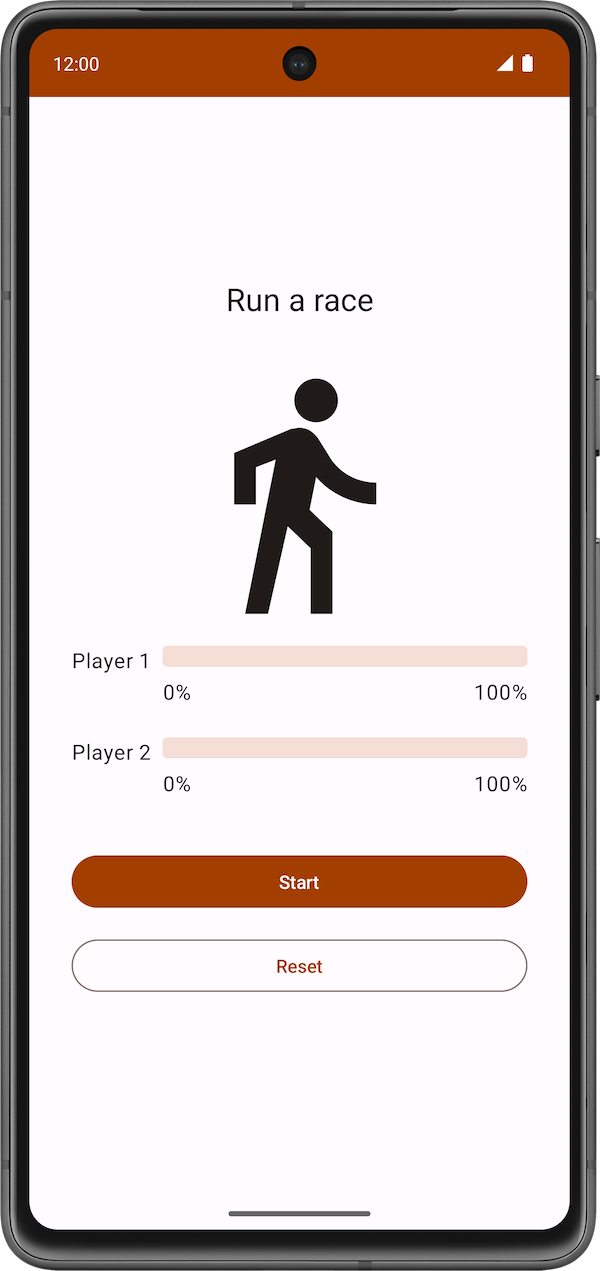

Race Tracker app¶

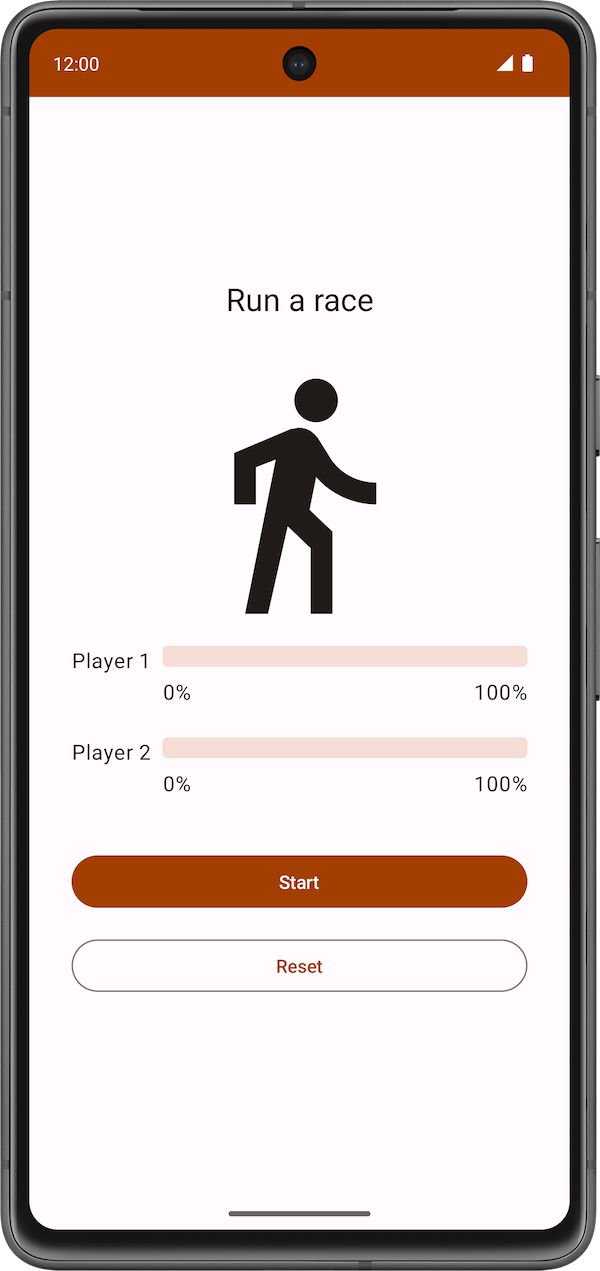

The Race Tracker app simulates two players running a race. The app UI consists of two buttons, Start/Pause and Reset, and two progress bars to show the progress of the racers. Players 1 and 2 are set to “run” the race at different speeds. When the race starts Player 2 progresses twice as fast as Player 1.

Coroutines are used to ensure:

Both players “run the race” concurrently.

The app UI is responsive and the progress bars increments during the race.

The starter code has the UI code ready for the Race Tracker app. The main focus of this part of the codelab is to get you familiar with Kotlin coroutines inside an Android app.

Starter code: Race Tracker app¶

Branch: starter

Clone:

$ git clone https://github.com/google-developer-training/basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-race-tracker.git $ cd basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-race-tracker $ git checkout starter

Starter code overview: Race Tracker app¶

Start the race by clicking the Start button. The text of the Start button changes to Pause while the race is in progress.

At any point in time, you can use this button to pause or continue the race.

When the race starts, you can see the progress of each player through a status indicator. The

StatusIndicatorcomposable function displays the progress status of each player. It uses theLinearProgressIndicatorcomposable to display the progress bar. You’ll be using coroutines to update the value for progress.

RaceParticipant.kt➜class RaceParticipantprovides the data for progress increment. This class is a state holder for each of the players. It maintains:the

nameof the participantthe

maxProgressto reach to finish the racethe delay duration between progress increments

currentProgressin racethe

initialProgress

In the next section, you will use coroutines to implement the functionality to simulate the race progress without blocking the app UI.

Implement race progress¶

In

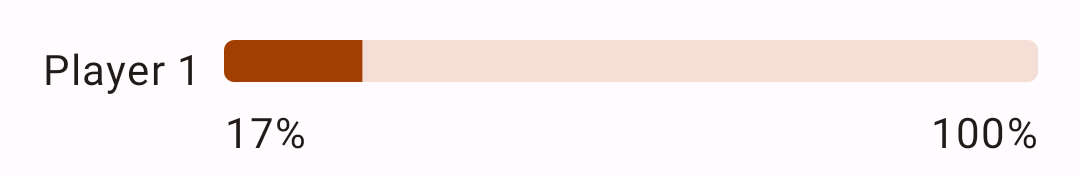

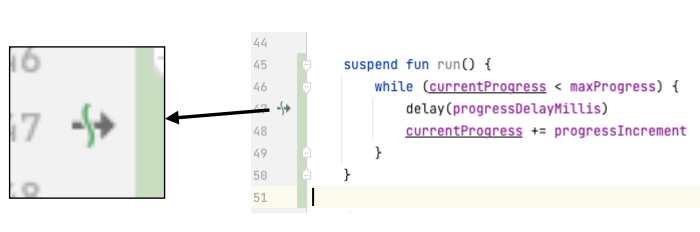

RaceParticipant.kt➜class RaceParticipant, add arun()function:class RaceParticipant( val name: String, val maxProgress: Int = 100, val progressDelayMillis: Long = 500L, private val progressIncrement: Int = 1, private val initialProgress: Int = 0 ) { init { require(maxProgress > 0) { "maxProgress=$maxProgress; must be > 0" } require(progressIncrement > 0) { "progressIncrement=$progressIncrement; must be > 0" } } /** * Indicates the race participant's current progress */ var currentProgress by mutableStateOf(initialProgress) private set suspend fun run() { while (currentProgress < maxProgress) { // Simulate different progress intervals in the race delay(progressDelayMillis) // Simulate the runner's progress currentProgress += progressIncrement } } /** * Regardless of the value of [initialProgress] the reset function will reset the * [currentProgress] to 0 */ fun reset() { currentProgress = 0 } }

imports

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

When you look at the code you just added, you will see an icon on the left of the call to the

delay()function in Android Studio, as shown in the screenshot below:

This icon indicates the suspension point when the function might suspend and resume again later.

The main thread is not blocked while the coroutine is waiting to complete the delay duration, as shown in the following diagram:

The coroutine suspends (but doesn’t block) the execution after calling the

delay()function with the desired interval value. Once the delay is complete, the coroutine resumes the execution and updates the value of thecurrentProgressproperty.

Start the race¶

In

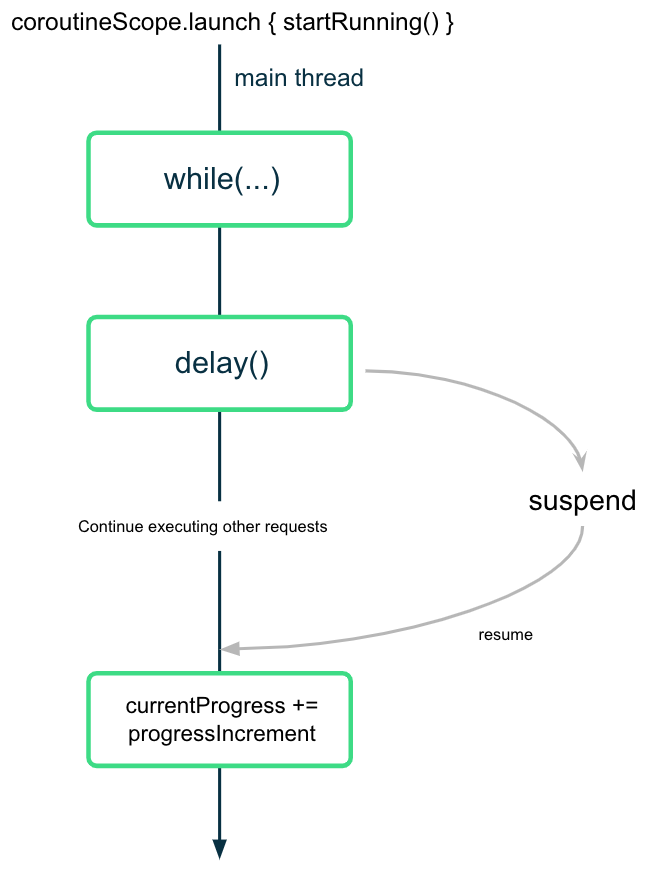

RaceTrackerApp.kt➜RaceTrackerApp(), add this code:@Composable fun RaceTrackerApp() { /** * Note: To survive the configuration changes such as screen rotation, [rememberSaveable] should * be used with custom Saver object. But to keep the example simple, and keep focus on * Coroutines that implementation detail is stripped out. */ val playerOne = remember { RaceParticipant(name = "Player 1", progressIncrement = 1) } val playerTwo = remember { RaceParticipant(name = "Player 2", progressIncrement = 2) } var raceInProgress by remember { mutableStateOf(false) } // added code begin if (raceInProgress) { LaunchedEffect(playerOne, playerTwo) { coroutineScope { launch { playerOne.run() } launch { playerTwo.run() } } raceInProgress = false } } // added code end RaceTrackerScreen( playerOne = playerOne, playerTwo = playerTwo, isRunning = raceInProgress, onRunStateChange = { raceInProgress = it }, modifier = Modifier .statusBarsPadding() .fillMaxSize() .verticalScroll(rememberScrollState()) .safeDrawingPadding() .padding(horizontal = dimensionResource(R.dimen.padding_medium)), ) }

imports

import androidx.compose.runtime.LaunchedEffect

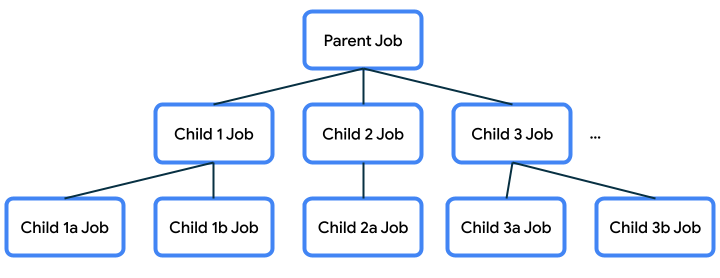

When the user presses Start,

raceInProgressis set totrue.The code inside the

if (raceInProgress)block runs.The

LaunchedEffect()function enters the Composition.The

coroutineScope()launches 2 coroutines concurrently. It ensures that both coroutines complete execution, before updating theraceInProgressflag.When

raceInProgressisfalse, theLaunchedEffect()exits the composition. The 2 coroutines are canceled.

Structured concurrency¶

The way you write code using coroutines is called structured concurrency. The idea is that coroutines have a hierarchy — tasks might launch subtasks, which might launch subtasks in turn. The unit of this hierarchy is referred to as a coroutine scope. Coroutine scopes should always be associated with a lifecycle.

The Coroutines APIs adhere to this structured concurrency by design. You cannot call a suspend function from a function which is not marked suspend. This limitation ensures that you call the suspend functions from coroutine builders, such as

launch. These builders are, in turn, tied to aCoroutineScope.Run the app.

Click the Start button. Player 2 runs faster than Player 1. After the race is complete, which is when both players reach 100% progress, the label for the Pause button changes to Start. You can click the Reset button to reset the race and re-execute the simulation. The race is shown in the following video.

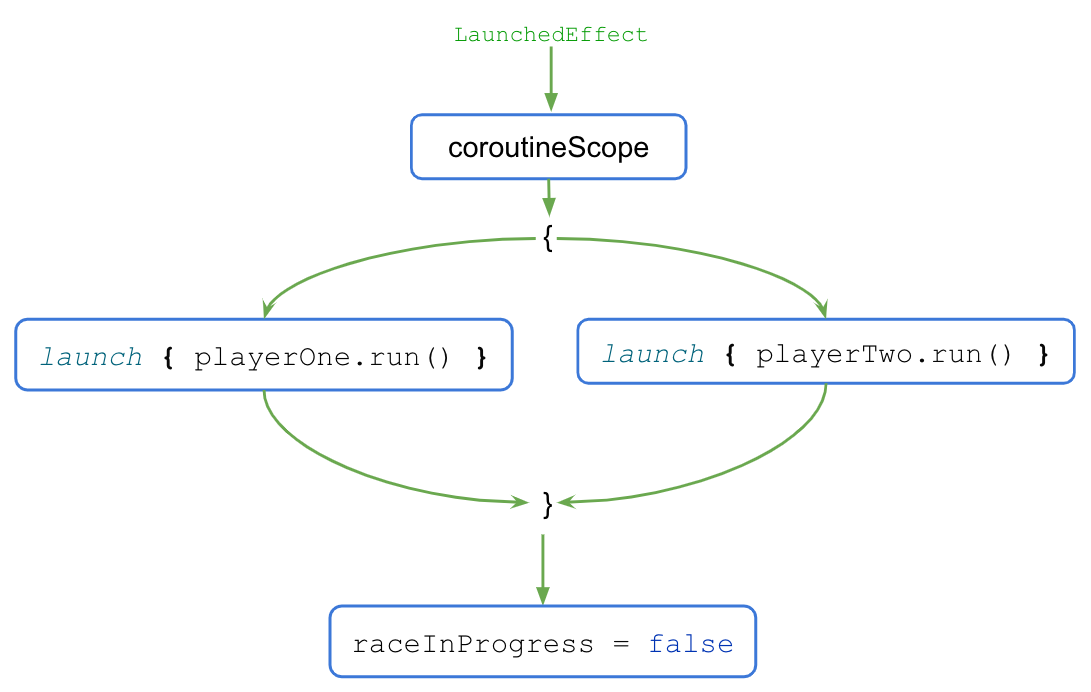

The execution flow is shown in the following diagram.

When the

LaunchedEffect()block executes, the control is transferred to thecoroutineScope{..}block.The

coroutineScopeblock launches both coroutines concurrently and waits for them to finish execution.Once the execution is complete, the

raceInProgressflag updates.The

coroutineScopeblock only returns and moves on after all the code inside the block completes execution. For the code outside of the block, the presence or absence of concurrency becomes a mere implementation detail. This coding style provides a structured approach to concurrent programming and is referred to as structured concurrency.When you click the Reset button after the race completes, the coroutines are canceled, and the progress for both players is reset to

0.

Solution code¶

Branch: main

Clone:

$ git clone https://github.com/google-developer-training/basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-race-tracker.git $ cd basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-race-tracker $ git checkout main

HTTP/REST¶

Most Android apps connect to the internet to perform network operations, such as retrieving emails, messages, or other information from a backend server.

We will use open source and community-driven libraries to build a data layer and get data from a backend server. This greatly simplifies fetching the data and also helps the app follow Android best practices, such as perform operations on a background thread. We will also display an error message if the internet is slow or unavailable, which will keep the user informed about any network connectivity issues.

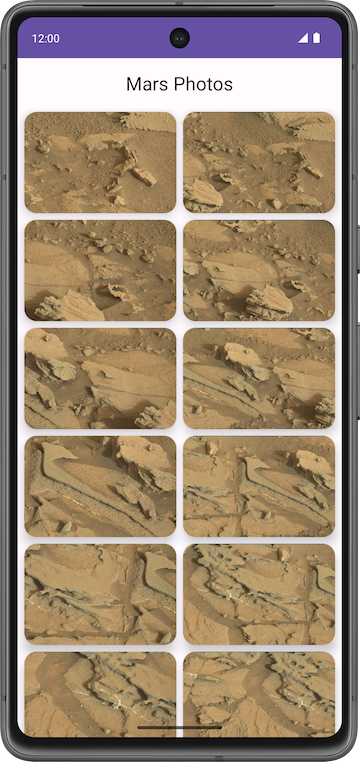

Mars Photos app¶

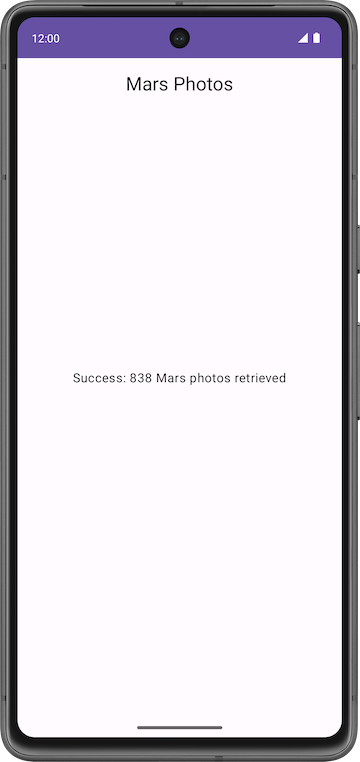

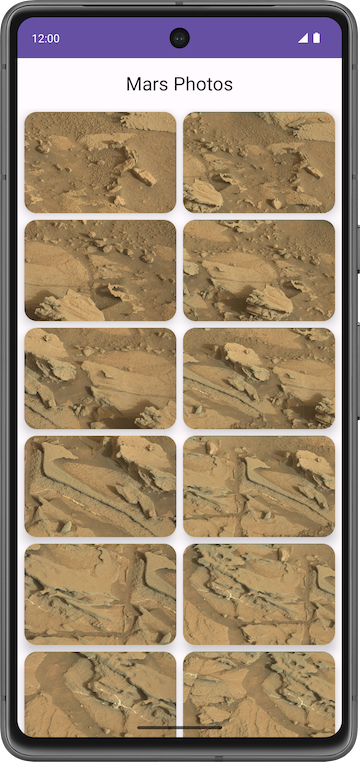

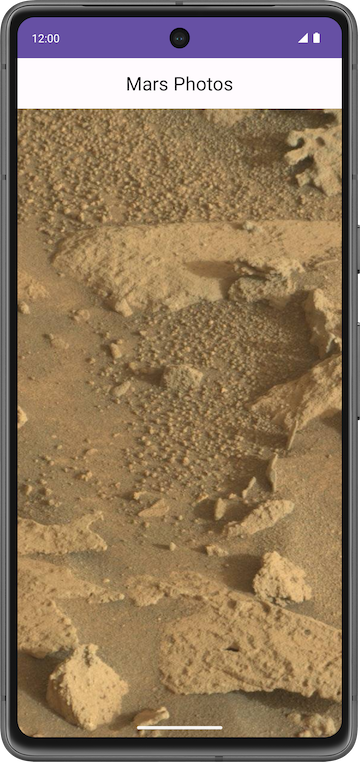

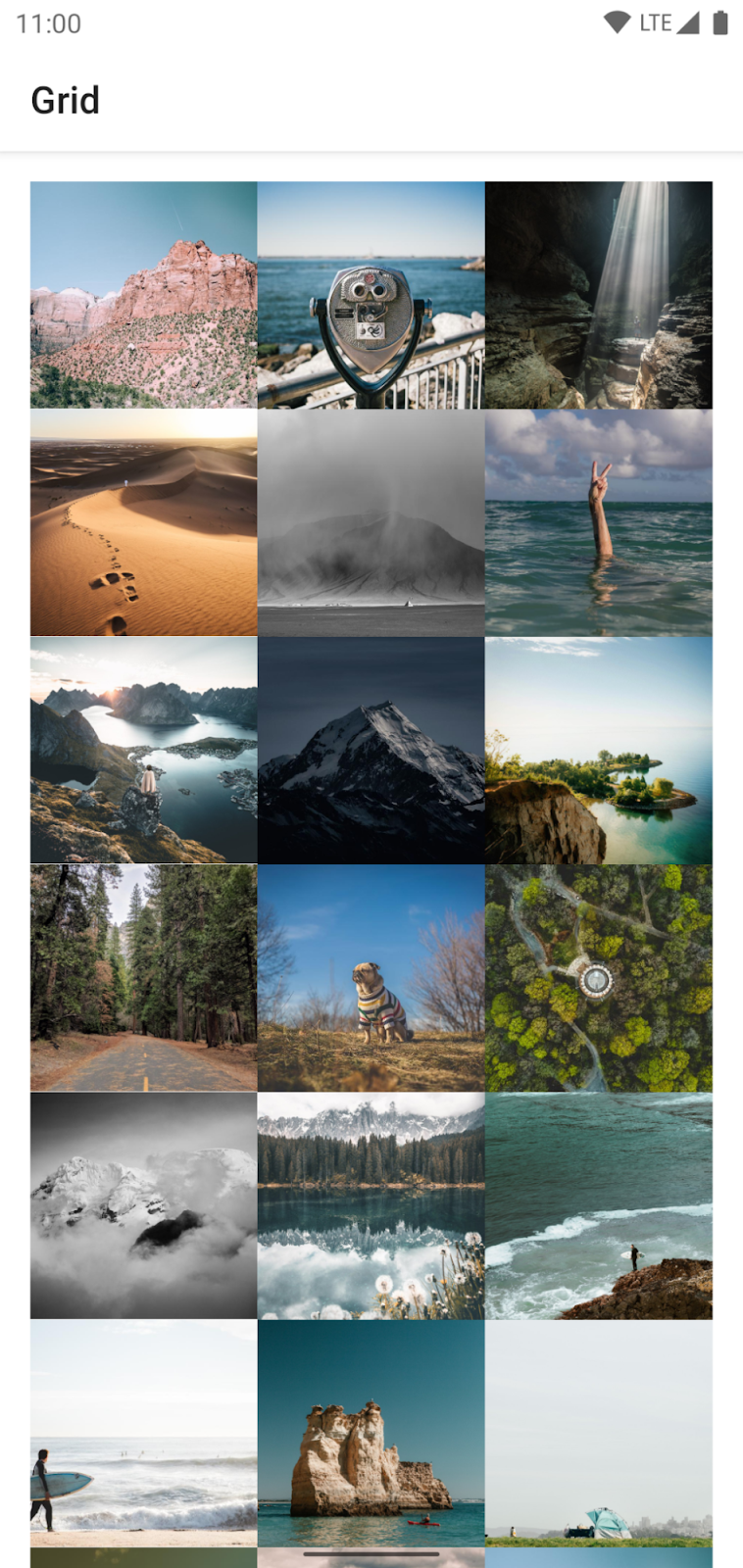

You work with the app named Mars Photos, which shows images of the Mars surface. This app connects to a web service to retrieve and display Mars photos. The images are real-life photos from Mars, captured from NASA’s Mars rovers. The following image is a screenshot of the final app, which contains a grid of images.

Note

The preceding image is a screenshot of the final app that you will build at the end of this unit, after additional updates in later codelabs. The screenshot is shown in this codelab to give you a better idea of the overall app functionality.

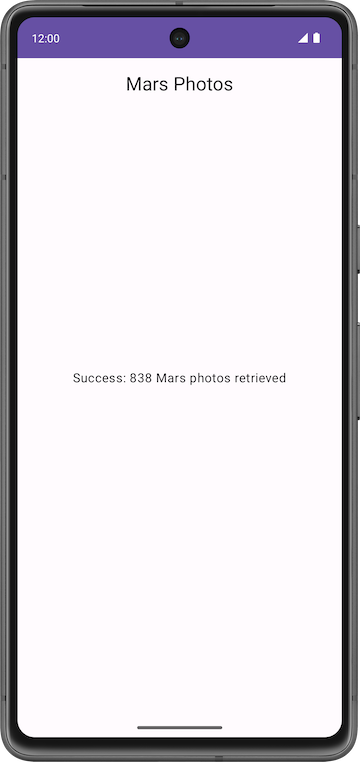

The version of the app you build in this codelab won’t have a lot of bling. This codelab focuses on the data layer part of the app to connect to the internet and download the raw property data using a web service. To ensure that the app correctly retrieves and parses this data, you can print the number of photos received from the backend server in a

Textcomposable.

Solution code: Mars Photos app¶

Branch: repo-starter

Clone:

$ git clone https://github.com/google-developer-training/basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-mars-photos.git $ cd basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-mars-photos $ git checkout repo-starter

We’ll start with the solution code and learn how it works.

Solution code overview: Mars Photos app¶

network/MarsApiService.ktpackage com.example.marsphotos.network import com.example.marsphotos.model.MarsPhoto import com.jakewharton.retrofit2.converter.kotlinx.serialization.asConverterFactory import kotlinx.serialization.json.Json import okhttp3.MediaType.Companion.toMediaType import retrofit2.Retrofit import retrofit2.http.GET private const val BASE_URL = "https://android-kotlin-fun-mars-server.appspot.com" /** * Use the Retrofit builder to build a retrofit object using a kotlinx.serialization converter */ private val retrofit = Retrofit.Builder() // Creates a Retrofit object. The following lines add various functionality to this object. .addConverterFactory(Json.asConverterFactory("application/json".toMediaType())) // Adds functionality that converts the web service's response into Kotlin objects .baseUrl(BASE_URL) // Tells the Retrofit object which base URL to use when making web service requests .build() // builds the Retrofit object /** * Retrofit service object for creating api calls */ interface MarsApiService { // Gets the response from the web service, and returns it as a List of MarsPhoto objects. // The @GET annotation tells Retrofit that this is a GET request, and that the endpoint is "{BASE_URL}/photos" @GET("photos") suspend fun getPhotos(): List<MarsPhoto> } /** * A public Api object that exposes the lazy-initialized Retrofit service */ object MarsApi { val retrofitService: MarsApiService by lazy { retrofit.create(MarsApiService::class.java) } }

BASE_URLis the base URL for the web service.interface MarsApiServicedefines how Retrofit talks to the web server using HTTP requests. WhenevergetPhotos()is called:Retrofit makes a request to

{BASE_URL}/photos.Retrofit receives a response. This response is a JSON string.

Because of

.addConverterFactory(Json.asConverterFactory("application/json".toMediaType()))andfun getPhotos(): List<MarsPhoto>, Retrofit converts the JSON string intoList<MarsPhoto>, i.e. a list ofMarsPhotoobjects.

object MarsApiis a singleton object used to access the retrofit service. The app needs only one retrofit service, so this object is created to make sure that only one instance of the retrofit service is created.

ui/MarsPhotosApp.kt@file:OptIn(ExperimentalMaterial3Api::class) package com.example.marsphotos.ui import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.fillMaxSize import androidx.compose.material3.CenterAlignedTopAppBar import androidx.compose.material3.ExperimentalMaterial3Api import androidx.compose.material3.MaterialTheme import androidx.compose.material3.Scaffold import androidx.compose.material3.Surface import androidx.compose.material3.Text import androidx.compose.material3.TopAppBarDefaults import androidx.compose.material3.TopAppBarScrollBehavior import androidx.compose.runtime.Composable import androidx.compose.ui.Modifier import androidx.compose.ui.input.nestedscroll.nestedScroll import androidx.compose.ui.res.stringResource import androidx.lifecycle.viewmodel.compose.viewModel import com.example.marsphotos.R import com.example.marsphotos.ui.screens.HomeScreen import com.example.marsphotos.ui.screens.MarsViewModel @Composable fun MarsPhotosApp() { val scrollBehavior = TopAppBarDefaults.enterAlwaysScrollBehavior() Scaffold( modifier = Modifier.nestedScroll(scrollBehavior.nestedScrollConnection), topBar = { MarsTopAppBar(scrollBehavior = scrollBehavior) } ) { Surface( modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize() ) { val marsViewModel: MarsViewModel = viewModel() HomeScreen( marsUiState = marsViewModel.marsUiState, contentPadding = it ) } } } @Composable fun MarsTopAppBar(scrollBehavior: TopAppBarScrollBehavior, modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { CenterAlignedTopAppBar( scrollBehavior = scrollBehavior, title = { Text( text = stringResource(R.string.app_name), style = MaterialTheme.typography.headlineSmall, ) }, modifier = modifier ) }

MarsPhotosAppdisplays the contents on the screen: the top app bar, theHomeScreencomposable, etc.

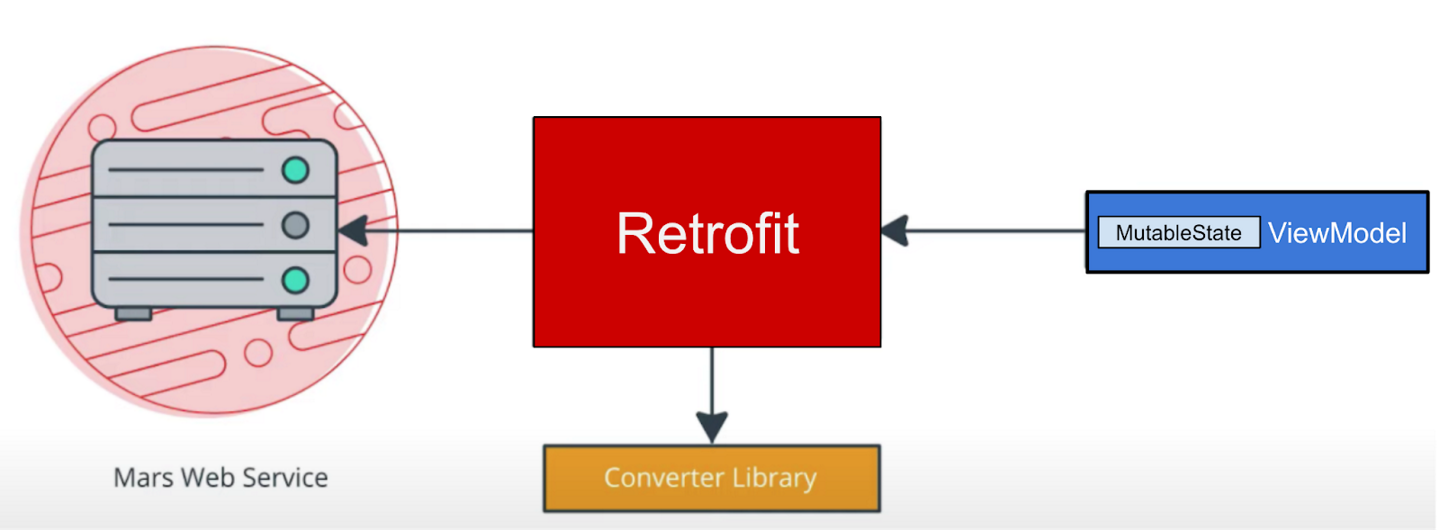

screens/MarsViewModel.ktpackage com.example.marsphotos.ui.screens import androidx.compose.runtime.getValue import androidx.compose.runtime.mutableStateOf import androidx.compose.runtime.setValue import androidx.lifecycle.ViewModel import androidx.lifecycle.viewModelScope import com.example.marsphotos.model.MarsPhoto import com.example.marsphotos.network.MarsApi import kotlinx.coroutines.launch import retrofit2.HttpException import java.io.IOException /** * UI state for the Home screen */ sealed interface MarsUiState { data class Success(val photos: String) : MarsUiState object Error : MarsUiState object Loading : MarsUiState } class MarsViewModel : ViewModel() { /** The mutable State that stores the status of the most recent request */ var marsUiState: MarsUiState by mutableStateOf(MarsUiState.Loading) private set /** * Call getMarsPhotos() on init so we can display status immediately. */ init { getMarsPhotos() } /** * Gets Mars photos information from the Mars API Retrofit service and updates the * [MarsPhoto] [List] [MutableList]. */ fun getMarsPhotos() { viewModelScope.launch { marsUiState = MarsUiState.Loading marsUiState = try { val listResult = MarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos() MarsUiState.Success( "Success: ${listResult.size} Mars photos retrieved" ) } catch (e: IOException) { MarsUiState.Error } catch (e: HttpException) { MarsUiState.Error } } } }

This file is the corresponding view model for the

MarsPhotosApp.This class contains a

MutableStateproperty namedmarsUiState. It stores the status of the most recent request.

screens/HomeScreen.ktpackage com.example.marsphotos.ui.screens import androidx.compose.foundation.Image import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.Arrangement import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.Box import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.Column import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.PaddingValues import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.fillMaxSize import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.fillMaxWidth import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.padding import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.size import androidx.compose.material3.Text import androidx.compose.runtime.Composable import androidx.compose.ui.Alignment import androidx.compose.ui.Modifier import androidx.compose.ui.res.painterResource import androidx.compose.ui.res.stringResource import androidx.compose.ui.tooling.preview.Preview import androidx.compose.ui.unit.dp import com.example.marsphotos.R import com.example.marsphotos.ui.theme.MarsPhotosTheme @Composable fun HomeScreen( marsUiState: MarsUiState, modifier: Modifier = Modifier, contentPadding: PaddingValues = PaddingValues(0.dp), ) { when (marsUiState) { is MarsUiState.Loading -> LoadingScreen(modifier = modifier.fillMaxSize()) is MarsUiState.Success -> ResultScreen( marsUiState.photos, modifier = modifier.fillMaxWidth() ) is MarsUiState.Error -> ErrorScreen( modifier = modifier.fillMaxSize()) } } /** * The home screen displaying the loading message. */ @Composable fun LoadingScreen(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { Image( modifier = modifier.size(200.dp), painter = painterResource(R.drawable.loading_img), contentDescription = stringResource(R.string.loading) ) } /** * The home screen displaying error message with re-attempt button. */ @Composable fun ErrorScreen(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { Column( modifier = modifier, verticalArrangement = Arrangement.Center, horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally ) { Image( painter = painterResource(id = R.drawable.ic_connection_error), contentDescription = "" ) Text(text = stringResource(R.string.loading_failed), modifier = Modifier.padding(16.dp)) } } /** * ResultScreen displaying number of photos retrieved. */ @Composable fun ResultScreen(photos: String, modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { Box( contentAlignment = Alignment.Center, modifier = modifier ) { Text(text = photos) } } @Preview(showBackground = true) @Composable fun LoadingScreenPreview() { MarsPhotosTheme { LoadingScreen() } } @Preview(showBackground = true) @Composable fun ErrorScreenPreview() { MarsPhotosTheme { ErrorScreen() } } @Preview(showBackground = true) @Composable fun PhotosGridScreenPreview() { MarsPhotosTheme { ResultScreen(stringResource(R.string.placeholder_success)) } }

This file contains the

HomeScreenandResultScreencomposables. TheResultScreenhas a simpleBoxlayout that displays the value ofmarsUiStatein aTextcomposable.

MainActivity.kt:The only task for this activity is to load the

ViewModeland display theMarsPhotosAppcomposable.

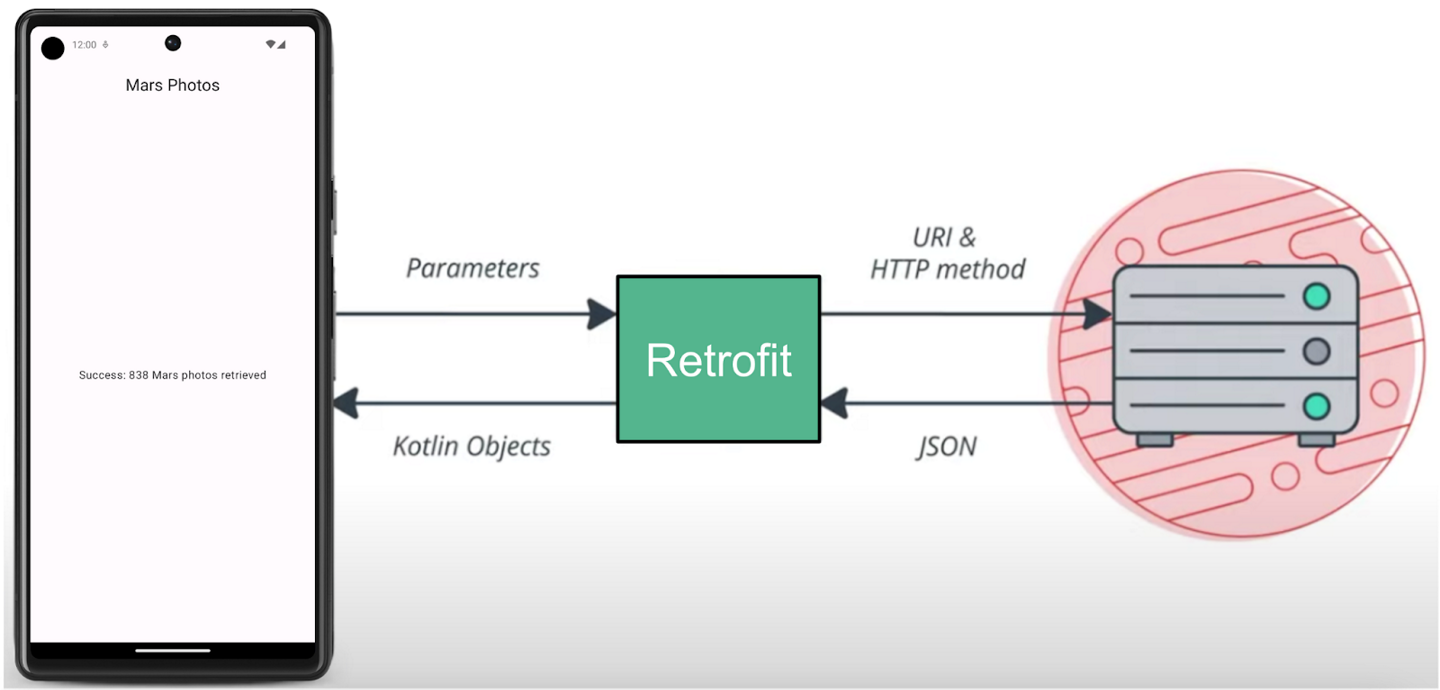

Web services and Retrofit¶

We’ll create a layer for the network service that communicates with the backend server and fetches the required data. We’ll use a third-party library, called Retrofit, to implement this task.

The

MarsViewModelis responsible for making the network call to get the Mars photos data. In theViewModel, useMutableStateto update the app UI when the data changes.Note

In later codelabs, we’ll add a Repository to your data layer. The Repository then communicates with the Retrofit service to fetch the data. The Repository is responsible for exposing the data to the rest of the app.

The Mars photos data is stored on a web server. To get this data into your app, you need to establish a connection and communicate with the server on the internet.

Note

In this codelab, you only retrieve the URLs, not the Mars photos. In a later codelab, you retrieve the Mars photos and display them in a grid.

Most web servers today run web services using a common stateless web architecture known as REpresentational State Transfer (REST). Web services that offer this architecture are known as RESTful services.

Requests are made to RESTful web services in a standardized way, via Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs). A URI identifies a resource in the server by name, without implying its location or how to access it. For example, in the app for this lesson, you retrieve the image URLs using the following server URI. This server hosts both Mars real estate and Mars photos:

Note

This server is being accessed by a different sample app where it showcases Mars real estate, so this server has two different endpoints: one for Mars real estate and one for photos. For this course, you use the server to retrieve Mars photos.

A URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is a subset of a URI that specifies where a resource exists and the mechanism for retrieving it. For example:

This URL gets a list of available real estate properties on Mars: https://android-kotlin-fun-mars-server.appspot.com/realestate

This URL gets a list of Mars photos: https://android-kotlin-fun-mars-server.appspot.com/photos

These URLs refer to an identified resource, such as /realestate or /photos, that is obtainable via the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (http:) from the network. You are using the /photos endpoint in this codelab. An endpoint is a URL that allows you to access a web service running on a server.

Note

The familiar web URL is actually a type of URI. This course uses both URL and URI interchangeably.

Web service request¶

Each web service request contains a URI and is transferred to the server using the same HTTP protocol that’s used by web browsers, like Chrome. HTTP requests contain an operation to tell the server what to do.

Common HTTP operations include:

GET for retrieving server data.

POST for creating new data.

PUT for updating existing data.

DELETE for deleting data.

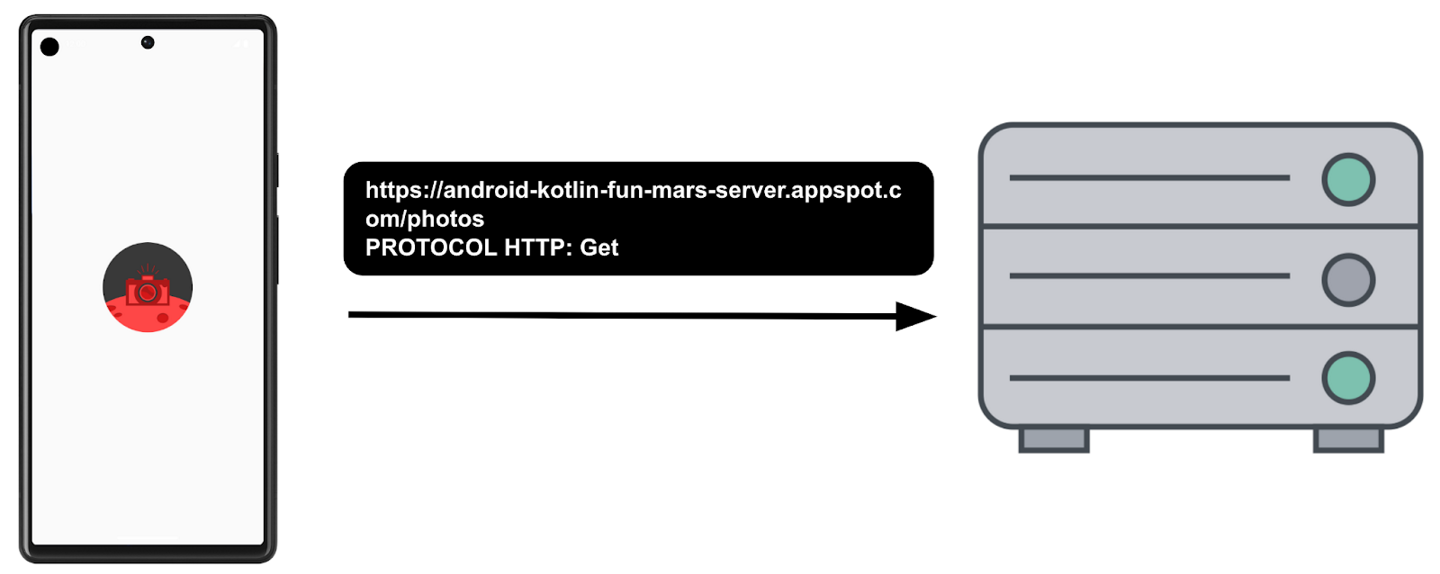

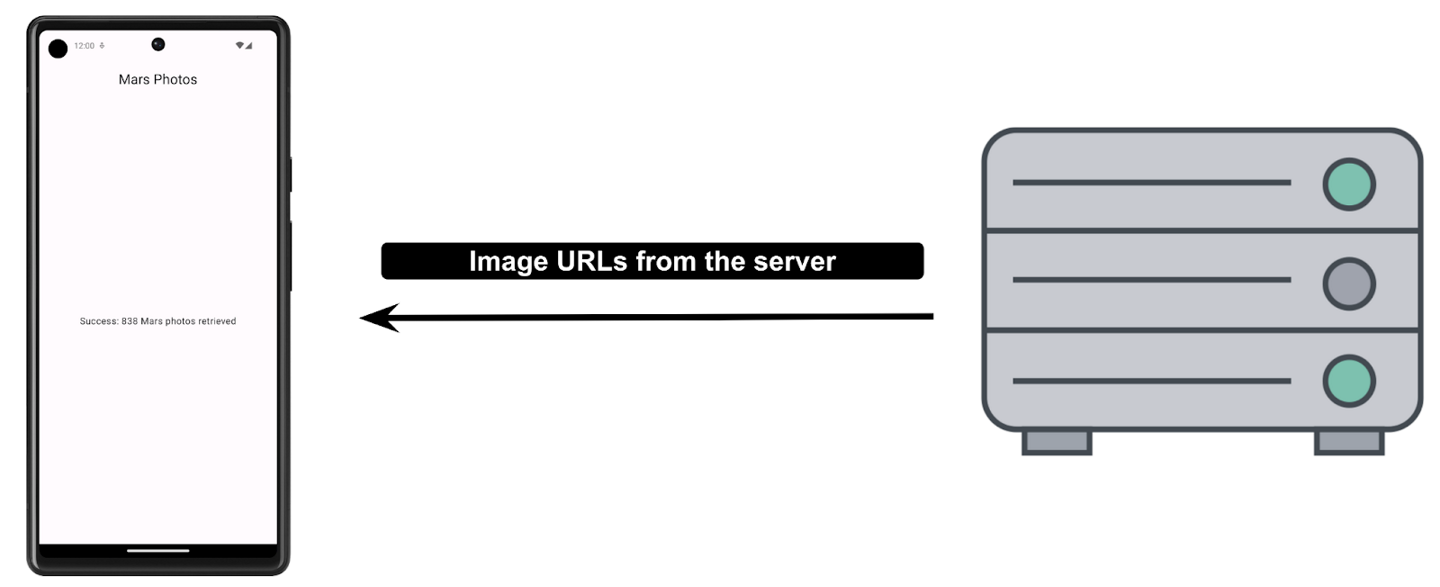

Your app makes an HTTP GET request to the server for the Mars photos information, and then the server returns a response to your app, including the image URLs.

The response from a web service is formatted in one of the common data formats, like XML (eXtensible Markup Language) or JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). The JSON format represents structured data in key-value pairs.

The app establishes a network connection to the server, sends a request, and receives a JSON response. The Retrofit library takes care of the communication with the server.

External Libraries¶

External libraries, or third-party libraries, are like extensions to the core Android APIs. The libraries you use in this course are open source, community-developed, and maintained by the collective contributions from the huge Android community around the world. These resources help Android developers like you to build better apps.

Warning

Using community-developed and maintained libraries can be a huge timesaver. However, choose these libraries wisely because your app is ultimately responsible for what the code does in these libraries.

Retrofit Library¶

The Retrofit library that you use in this codelab to talk to the RESTful Mars web service is a good example of a well-supported and maintained library. You can tell this by looking at its GitHub page and reviewing the open and closed issues (some are feature requests). If the developers are regularly resolving the issues and responding to the feature requests, the library is likely well-maintained and a good candidate to use in the app. You can also refer to Retrofit documentation to learn more about the library.

The Retrofit library communicates with the REST backend. It takes URIs and parameters as input.

Retrofit dependencies¶

Android Gradle lets you add external libraries to your project. In addition to the library dependency, you also need to include the repository where the library is hosted.

For Retrofit, the libraries are added in the

build.gradle.kts (Module :app)file:dependencies { // ... // Retrofit implementation("com.jakewharton.retrofit:retrofit2-kotlinx-serialization-converter:1.0.0") implementation("com.squareup.retrofit2:retrofit:2.9.0") implementation("com.squareup.okhttp3:okhttp:4.11.0") implementation("io.coil-kt:coil-compose:2.4.0") // ... }

Connecting to the Internet¶

Retrofit fetches data from the web service, and converts it to some othe format (in this case, JSON). Retrofit includes built-in support for popular data formats, such as XML and JSON. Retrofit ultimately creates the code to call and consume this service for you, including critical details, such as running the requests on background threads.

In

network/MarsApiService.kt, this code creates a singleton object calledMarsApithat initializes the Retrofit service. The singleton pattern ensures that one, and only one, instance of the retrofit object is created.object MarsApi { val retrofitService : MarsApiService by lazy { retrofit.create(MarsApiService::class.java) } }

by lazycauses the retrofit object to be lazily initialized. Lazy initialization is when object creation is purposely delayed, until you actually need that object, to avoid unnecessary computation or use of other computing resources. Kotlin has first-class support for lazy instantiation.

Warning

Singleton pattern is not a recommended practice. Singletons represent global states that are hard to predict, particularly in tests. Objects should define which dependencies they need, instead of describing how to create them.

Dependency injection is preferred over the singleton pattern. More on Dependency injection later.

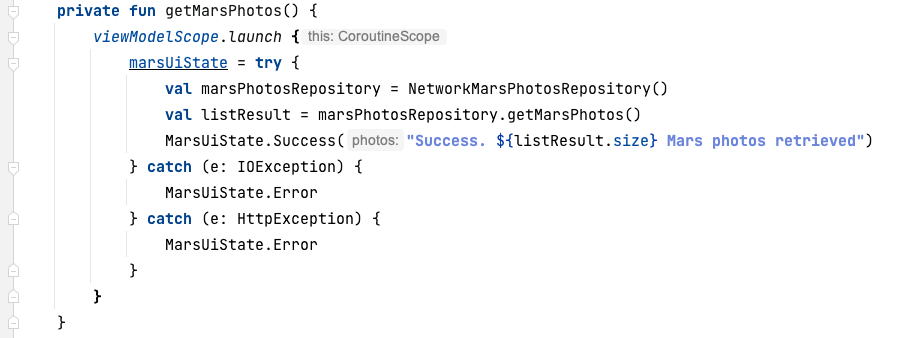

ViewModelScope¶

A

viewModelScopeis the built-in coroutine scope defined for eachViewModelin your app. Any coroutine launched in this scope is automatically canceled if theViewModelis cleared.You can use

viewModelScopeto launch the coroutine and make the web service request in the background. SinceviewModelScopebelongs toViewModel, the request continues even if the app goes through a configuration change.Inside

getMarsPhotos(),viewModelScope.launchlaunches the coroutine:private fun getMarsPhotos() { viewModelScope.launch { marsUiState = MarsUiState.Loading marsUiState = try { val listResult = MarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos() MarsUiState.Success( "Success: ${listResult.size} Mars photos retrieved" ) } catch (e: IOException) { MarsUiState.Error } catch (e: HttpException) { MarsUiState.Error } } }

Internet permissions¶

The purpose of permissions on Android is to protect the privacy of an Android user. Android apps must declare or request permissions to access sensitive user data, such as contacts, call logs, and certain system features, such as camera or internet.

In order for your app to access the Internet, it needs the

INTERNETpermission. Connecting to the internet introduces security concerns, which is why apps do not have internet connectivity by default. You need to explicitly declare that the app needs access to the internet. This declaration is considered a normal permission. To learn more about Android permissions and its types, please refer to the Permissions on Android.In

AndroidManifest.xml, here’s where the permission is declared:<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"> <uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INTERNET" /> <application android:allowBackup="true" android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher" android:label="@string/app_name" android:roundIcon="@mipmap/ic_launcher_round" android:supportsRtl="true" android:theme="@style/Theme.MarsPhotos" tools:targetApi="33"> <activity android:name=".MainActivity" android:exported="true" android:label="@string/app_name" android:theme="@style/Theme.MarsPhotos"> <intent-filter> <action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" /> <category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" /> </intent-filter> </activity> </application> </manifest>

Exception Handling¶

Exceptions are errors that can occur during runtime, not compile time, and they terminate the app abruptly without notifying the user. This can result in a poor user experience. Exception handling is a mechanism by which you prevent the app from terminating abruptly and handle the situation in a user-friendly way.

Examples of potential issues while connecting to a server include the following:

The URL or URI used in the API is incorrect.

The server is unavailable, and the app could not connect to it.

A network latency issue.

Poor or no internet connection on the device.

These exceptions can’t be handled during compile time, but you can use a

try-catchblock to handle the exception in runtime.Example syntax for try-catch block

try { // some code that can cause an exception. } catch (e: SomeException) { // handle the exception to avoid abrupt termination. }

Inside the

tryblock, you add the code where you anticipate an exception. In your app, this is a network call. In thecatchblock, you need to implement the code that prevents abrupt termination of the app. If there is an exception, then thecatchblock executes to recover from the error instead of terminating the app abruptly.In

MarsViewModel.kt➜getMarsPhotos(), this code handlesIOExceptionandHttpExceptionexceptions, settingMarsUiStateaccordingly. What exactly isMarsUiState? Read on to find out.fun getMarsPhotos() { viewModelScope.launch { marsUiState = MarsUiState.Loading marsUiState = try { val listResult = MarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos() MarsUiState.Success( "Success: ${listResult.size} Mars photos retrieved" ) } catch (e: IOException) { MarsUiState.Error } catch (e: HttpException) { MarsUiState.Error } } }

State UI¶

In the

MarsViewModelclass, the status of the most recent web request,marsUiState, is saved as a mutable state object. This class can represent 3 possible states:Loading: the app is waiting for data.

Success: the data was successfully retrieved from the web service.

Error: any network or connection errors.

To represent these three states in your application, a

sealed interfaceis used. Asealed interfacemakes it easy to manage state by limiting the possible values. InMarsViewModel.kt:sealed interface MarsUiState { data class Success(val photos: String) : MarsUiState object Error : MarsUiState object Loading : MarsUiState }

Using

sealed interfacelimits the values that themarsUiStateobject can have:When the response is successful, data is received from the server, and is stored in a newly created

data class Success.In the case of the

LoadingandErrorstates, we don’t need to store any data, just useobject Loadingandobject Error.

In

screens/HomeScreen.kt, we show a Loading, Result or Error screen depending on the value ofmarsUiState.import androidx.compose.foundation.layout.fillMaxSize fun HomeScreen( marsUiState: MarsUiState, modifier: Modifier = Modifier ) { when (marsUiState) { is MarsUiState.Loading -> LoadingScreen(modifier = modifier.fillMaxSize()) is MarsUiState.Success -> ResultScreen(marsUiState.photos, modifier = modifier.fillMaxWidth()) is MarsUiState.Error -> ErrorScreen( modifier = modifier.fillMaxSize()) } } @Composable fun LoadingScreen(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { // ... } @Composable fun ErrorScreen(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) { // ... }

Note

If you implement

MarsUiStateinterface without asealedkeyword, it requires you to add a Success, Error, Loading andelsebranch. Since there is no fourth option (else), you use asealedinterface to tell the compiler that there are only three options (thus making the conditionals exhaustive).

Parse JSON with kotlinx.serialization¶

JavaScript Object Notation¶

Web services typically respond in one of the common data formats like Extensible Markup Language (XML) or JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). Each call returns structured data, and your app needs to know what that structure is in order to read the data from the response.

For example, in this app, you are retrieving the data from https://android-kotlin-fun-mars-server.appspot.com/photos. When you enter this URL in the browser, you see a list of IDs and image URLs of the surface of Mars in a JSON format!

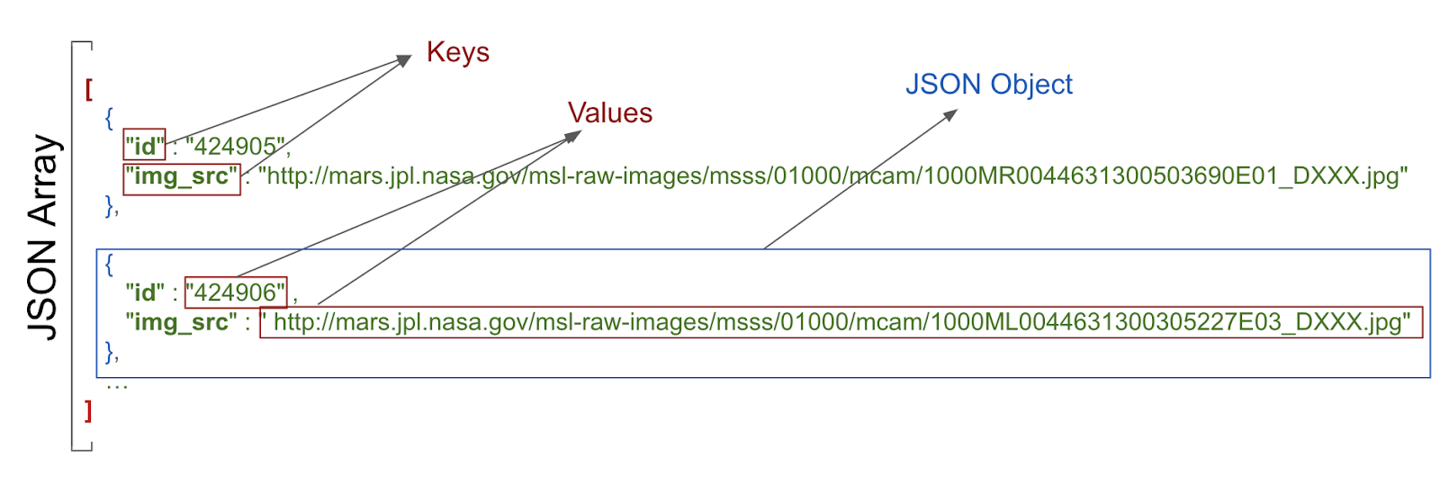

Structure of sample JSON response¶

The structure of a JSON response has the following features:

JSON response is an array, indicated by the square brackets. The array contains JSON objects.

JSON objects are surrounded by curly brackets.

Each JSON object contains a set of key-value pairs separated by a comma.

A colon separates the key and value in a pair.

Names are surrounded by quotes.

Values can be numbers, strings, a boolean, an array, an object (JSON object), or null.

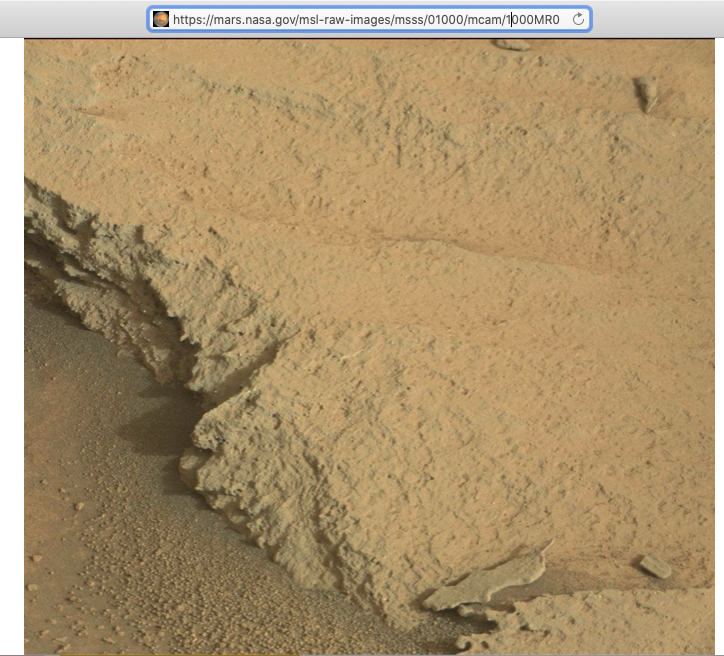

For example, the

img_srcis a URL, which is a string. When you paste the URL into a web browser, you see a Mars surface image.

In the app, Retrofit gets a JSON response from the Mars web service, and then converts them to Kotlin objects. This process is called deserialization.

Serialization is the process of converting data used by an application to a format that can be transferred over a network. As opposed to serialization, deserialization is the process of reading data from an external source (like a server) and converting it into a runtime object. They are both essential components of most applications that exchange data over the network.

kotlinx.serializationprovides sets of libraries that convert a JSON string into Kotlin objects. There is a community developed third party library that works with Retrofit, Kotlin Serialization Converter.

kotlinx.serialization library dependencies¶

Here are the dependencies in

build.gradle.kts (Module :app)plugins { // ... id("org.jetbrains.kotlin.plugin.serialization") version "1.9.10" } dependencies { // ... implementation("com.jakewharton.retrofit:retrofit2-kotlinx-serialization-converter:1.0.0") implementation("com.squareup.okhttp3:okhttp:4.11.0") implementation("org.jetbrains.kotlinx:kotlinx-serialization-json:1.6.0") // ... }

The Mars Photo data class¶

A sample entry of the JSON response you get from the web service looks something like the following:

[ { "id":"424906", "img_src":"http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl-raw-images/msss/01000/mcam/1000ML0044631300305227E03_DXXX.jpg" }, ...]In the example above, notice that each Mars photo entry has the following JSON key and value pairs:

id: the ID of the property, as a string. Since it is wrapped in quotes (" "), it is of the typeString, notInteger.img_src: The image’s URL, as a string.

kotlinx.serializationparses this JSON data and converts it into Kotlin objects. To do this,kotlinx.serializationneeds to have a Kotlin data class to store the parsed results.In

model/MarsPhoto.kt, the data class is:@Serializable data class MarsPhoto( val id: String, @SerialName(value = "img_src") val imgSrc: String )

The

@Serializableannotation is used to make the class serializable, which means it can be converted to and from a JSON string.Notice that each of the variables in the

MarsPhotoclass corresponds to a key name in the JSON object. To match the types in our specific JSON response, you useStringobjects for all the values.When

kotlinx serializationparses the JSON, it matches the keys by name and fills the data objects with appropriate values.

@SerialName Annotation¶

Sometimes the key names in a JSON response can make confusing Kotlin properties or may not match recommended coding style. For example, in the JSON file, the

img_srckey uses an underscore, whereas Kotlin convention for properties uses upper and lowercase letters (camel case).To use variable names in a data class that differ from the key names in the JSON response, use the

@SerialNameannotation. Indata class MarsPhoto, the name of the variable in the data class isimgSrc. The variable can be mapped to the JSON attributeimg_srcusing@SerialName(value = "img_src").

MarsApiService and MarsViewModel¶

In

network/MarsApiService.kt,kotlinx.serialization.json.Jsonconverts JSON to Kotlin objects. The code:import kotlinx.serialization.json.Json private val retrofit = Retrofit.Builder() .addConverterFactory(Json.asConverterFactory("application/json".toMediaType())) .baseUrl(BASE_URL) .build()

In

MarsViewModel.kt:getMarsPhotos()callsMarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos()MarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos():Sends a request to https://android-kotlin-fun-mars-server.appspot.com/photos

If successful, the response from the server will be a JSON string.

The JSON string is converted to a list of zero or more

MarsPhotoobjects.The list of

MarsPhotoobjects is returned togetMarsPhotos().

fun getMarsPhotos() { viewModelScope.launch { marsUiState = MarsUiState.Loading marsUiState = try { val listResult = MarsApi.retrofitService.getPhotos() MarsUiState.Success( "Success: ${listResult.size} Mars photos retrieved" ) } catch (e: IOException) { MarsUiState.Error } catch (e: HttpException) { MarsUiState.Error } } }

When the app is run, it should show the number of photos retrieved:

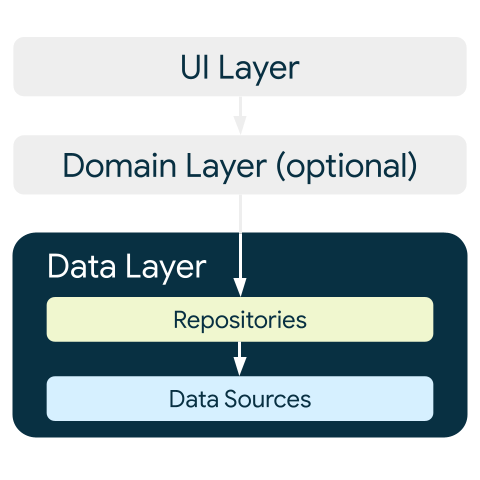

The Data Layer¶

Add repository and Manual Dependency Injection¶

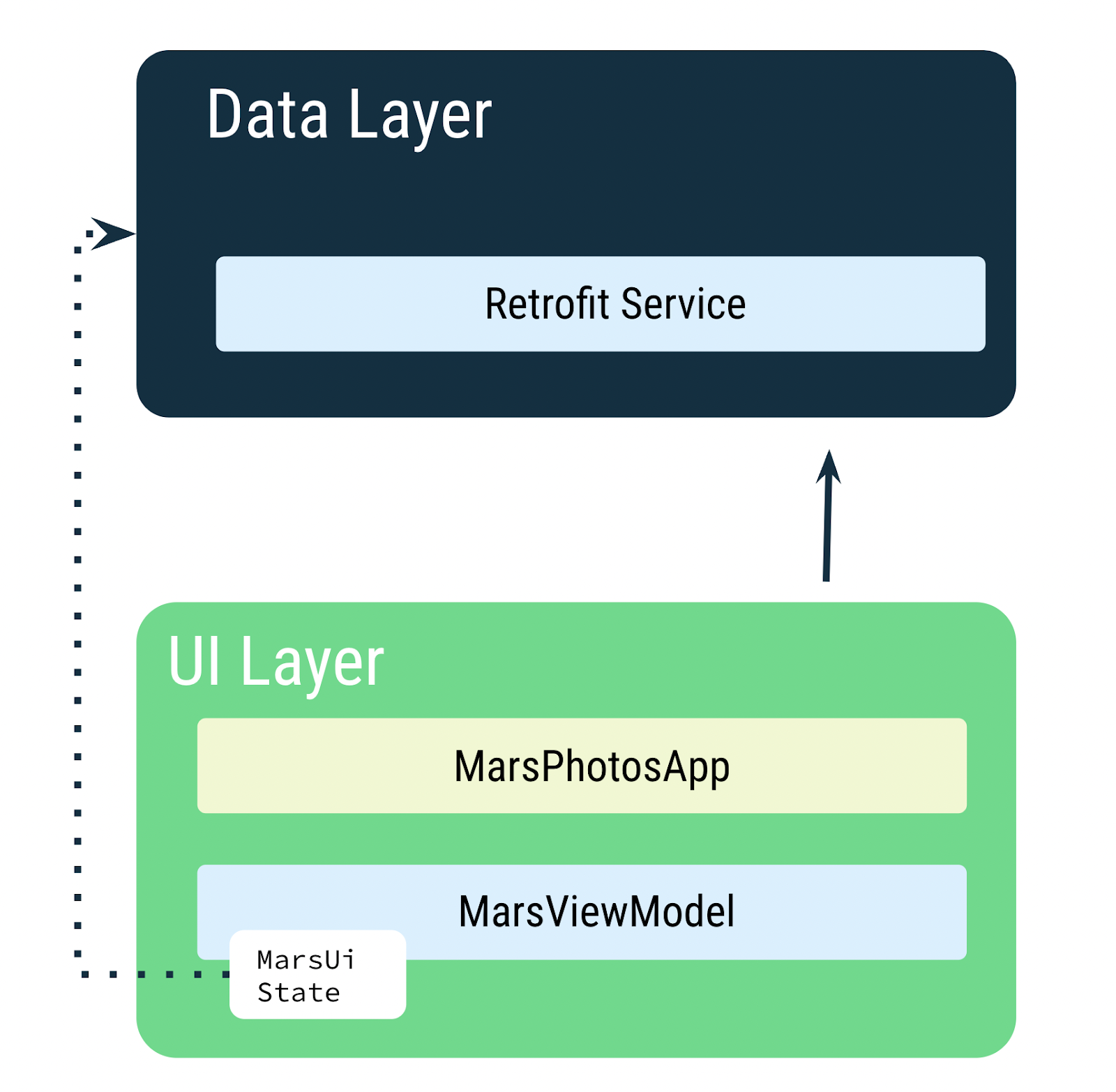

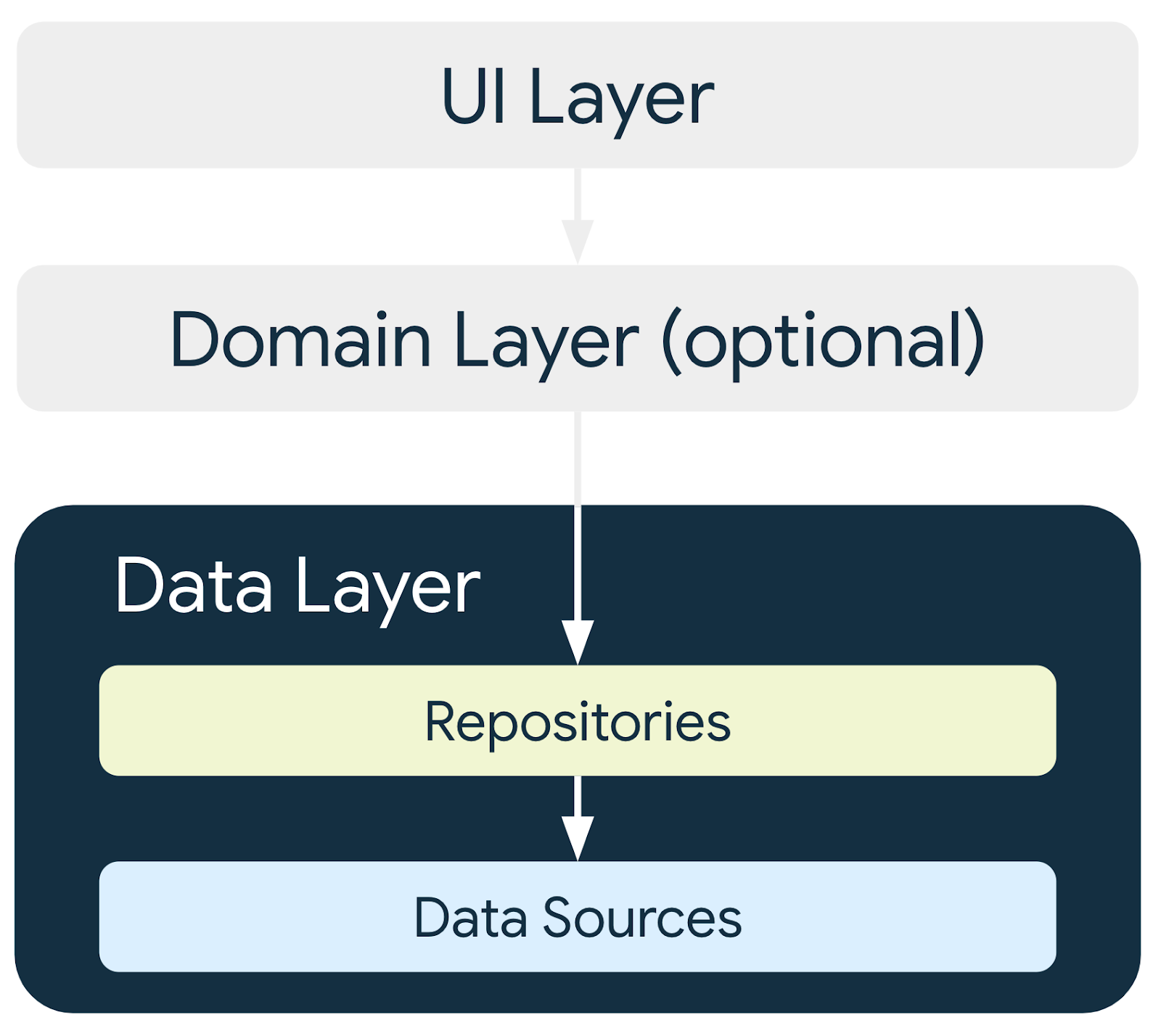

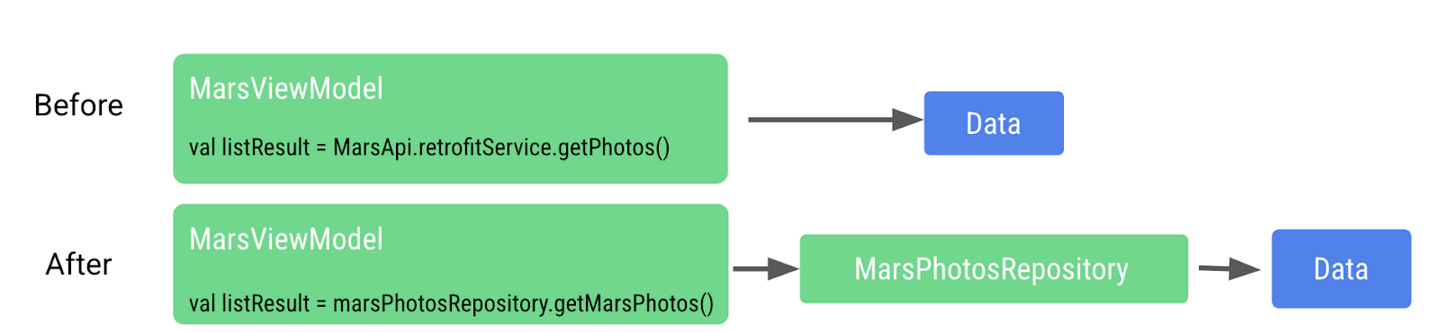

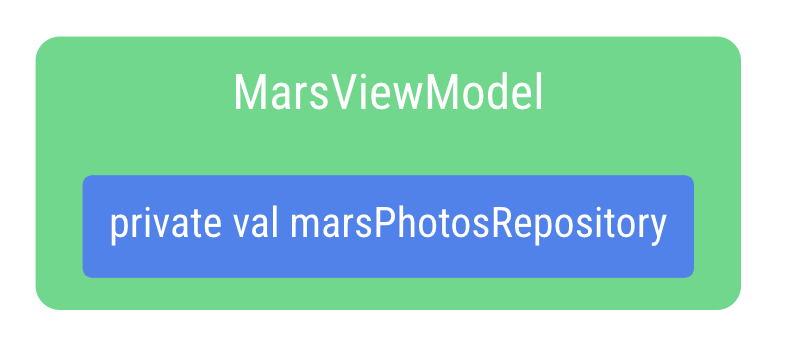

We’ve learnt how to get data from a web service by having the

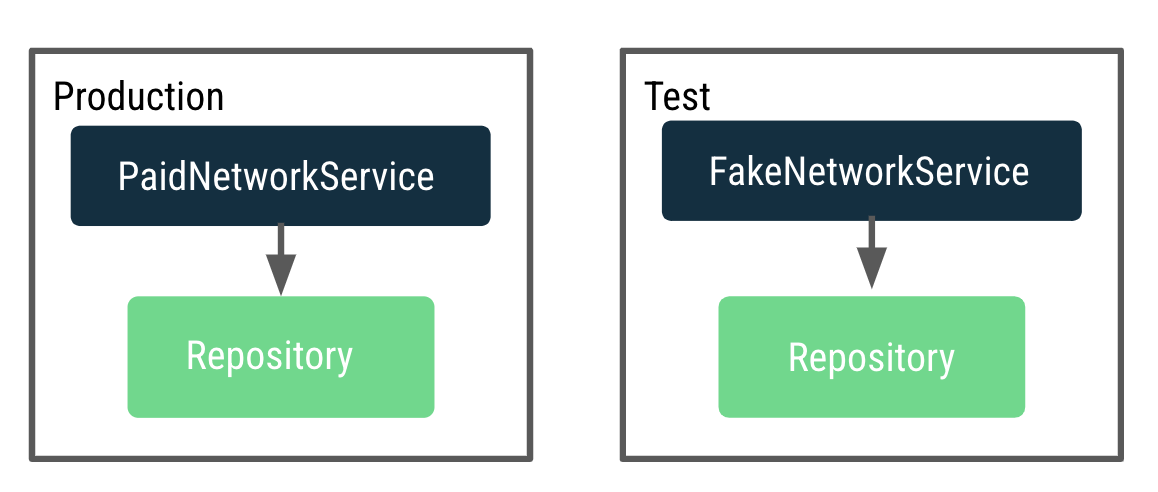

ViewModelretrieve the URLs of Mars photos from the network using an API service. While this approach works and is simple to implement, it does not scale well as your app grows and needs to work with more than one data source. To address this issue, Android architecture best practices recommend separating out your UI layer and data layer.We’ll refactor the Mars Photos app into separate UI and data layers. We’ll learn how to implement the repository pattern and use dependency injection. Dependency injection creates a more flexible coding structure that helps with development and testing.

Starter code: Mars Photos app, with data layer¶

Branch: repo-starter

Clone:

$ git clone https://github.com/google-developer-training/basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-mars-photos.git $ cd basic-android-kotlin-compose-training-mars-photos $ git checkout repo-starter

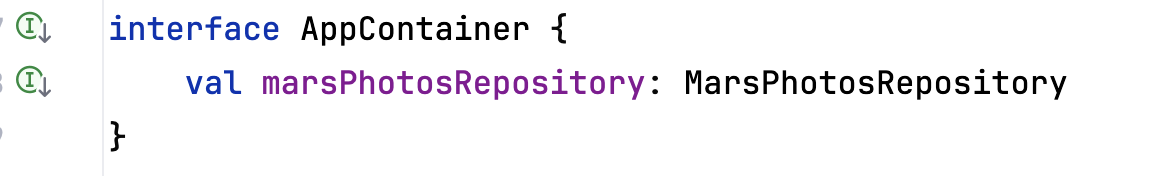

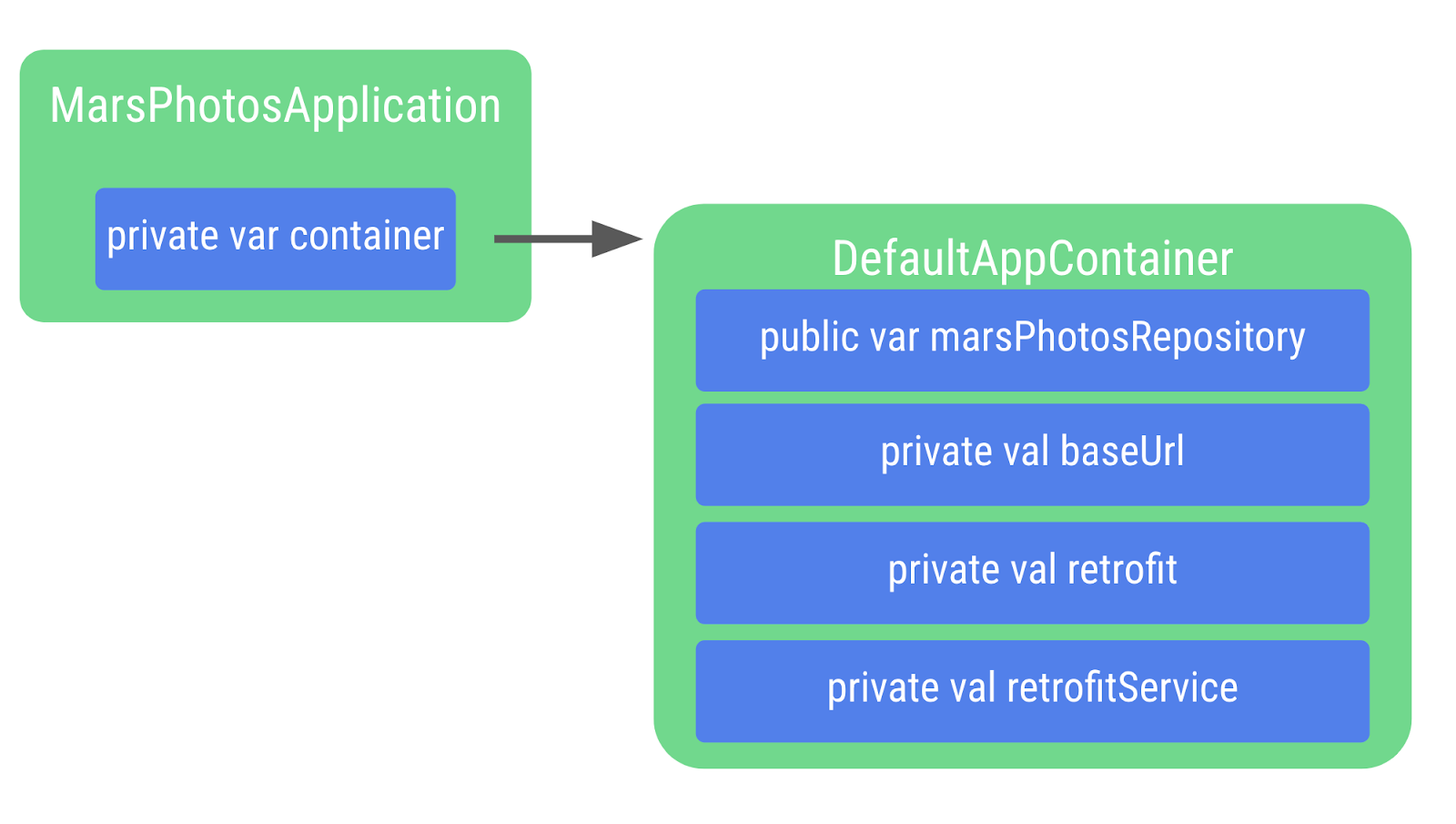

Separate the UI layer and Data layer¶

Why different layers?¶

Separating the code into different layers makes your app more scalable, more robust, and easier to test. Having multiple layers with clearly defined boundaries also makes it easier for multiple developers to work on the same app without negatively impacting each other.