Use classes and objects in Kotlin¶

Before you begin¶

Classes provide blueprints from which objects can be constructed. An object is an instance of a class that consists of data specific to that object. You can use objects or class instances interchangeably.

As an analogy, imagine that you build a house. A class is similar to an architect’s design plan, also known as a blueprint. The blueprint isn’t the house; it’s the instruction for how to build the house. The house is the actual thing, or object, which is built based on the blueprint.

Just like the house blueprint specifies multiple rooms and each room has its own design and purpose, each class has its own design and purpose. To know how to design your classes, you need to get familiar with object-oriented programming (OOP), a framework that teaches you to enclose data, logic, and behavior in objects.

OOP helps you simplify complex, real-world problems into smaller objects. There are four basic concepts of OOP, each of which you learn more about later in this codelab:

Encapsulation. Wraps related properties, and methods that perform actions on those properties, in a class. For example, a phone encapsulates a camera, display, memory cards, and several other hardware and software components. You don’t have to worry about how components are wired internally.

Abstraction. An extension to encapsulation. The idea is to hide the internal implementation logic as much as possible. For example, to take a photo with your mobile phone, all you need to do is open the camera app, point your phone to the scene that you want to capture, and click a button to capture the photo. You don’t need to know how the camera app is built or how the camera hardware on your mobile phone actually works. In short, the internal mechanics of the camera app and how a mobile camera captures the photos are abstracted to let you perform the tasks that matter.

Inheritance. Enables you to build a class upon the characteristics and behavior of other classes by establishing a parent-child relationship. For example, there are different manufacturers who produce a variety of mobile devices that run Android OS, but the UI for each of the devices is different. In other words, the manufacturers inherit the Android OS feature and build their customizations on top of it.

Polymorphism. The word is an adaptation of the Greek root poly-, which means many, and -morphism, which means forms. Polymorphism is the ability to use different objects in a single, common way. For example, when you connect a Bluetooth speaker to your mobile phone, the phone only needs to know that there’s a device that can play audio over Bluetooth. However, there are a variety of Bluetooth speakers that you can choose from and your phone doesn’t need to know how to work with each of them specifically.

Lastly, you learn about property delegates, which provide reusable code to manage property values with a concise syntax. In this codelab, you learn these concepts when you build a class structure for a smart-home app.

Note

Smart devices make our lives convenient and easier. There are many smart-home solutions available on the market that let you control smart devices with your smartphone. With a single tap on your mobile device, you can control a variety of devices, such as smart TVs, lights, thermostats, and other household appliances.

Prerequisites¶

How to open, edit, and run code in Kotlin Playground.

Knowledge of Kotlin programming basics, including variables, functions, and the

println()andmain()functions

What you’ll learn¶

An overview of OOP.

What classes are.

How to define a class with constructors, functions, and properties.

How to instantiate an object.

What inheritance is.

The difference between IS-A and HAS-A relationships.

How to override properties and functions.

What visibility modifiers are.

What a delegate is and how to use the by delegate.

What you’ll build¶

A smart-home class structure.

Classes that represent smart devices, such as a smart TV and a smart light.

Note

The code that you write won’t interact with real hardware devices. Instead, you print actions in the console with the

println()function to simulate the interactions.

What you’ll need¶

A computer with internet access and a web browser

Define a class¶

When you define a class, you specify the properties and methods that all objects of that class should have.

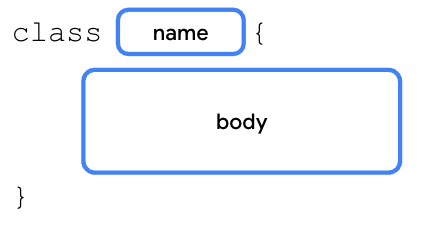

A class definition starts with the

classkeyword, followed by a name and a set of curly braces. The part of the syntax before the opening curly brace is also referred to as the class header. In the curly braces, you can specify properties and functions for the class. You learn about properties and functions soon. You can see the syntax of a class definition in this diagram:

These are the recommended naming conventions for a class:

You can choose any class name that you want, but don’t use Kotlin keywords as a class name, such as the

funkeyword.The class name is written in PascalCase, so each word begins with a capital letter and there are no spaces between the words. For example, in SmartDevice, the first letter of each word is capitalized and there isn’t a space between the words.

A class consists of three major parts:

Properties: variables that specify the attributes of the class’s objects.

Methods: functions that contain the class’s behaviors and actions.

Constructors: a special function that creates instances of the class throughout the program in which it’s defined.

This isn’t the first time that you’ve worked with classes. In previous codelabs, you learned about data types, such as the

Int,Float,String, andDoubledata types. These data types are defined as classes in Kotlin. When you define a variable as shown in this code snippet, you create an object of theIntclass, which is instantiated with a1value:val number: Int = 1

Example of a bare basic class:

class SmartDevice { // empty body } fun main() { }

Create an instance of a class¶

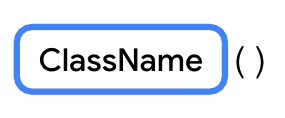

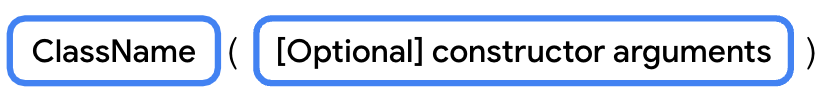

A class is a blueprint for an object. The Kotlin runtime uses the class, or blueprint, to create an object of that particular type. With the

SmartDeviceclass, you have a blueprint of what a smart device is. To have an actual smart device in your program, you need to create aSmartDeviceobject instance. Creating an object instance is known as instantiation. The instantiation syntax starts with the class name followed by a set of parentheses as you can see in this diagram:

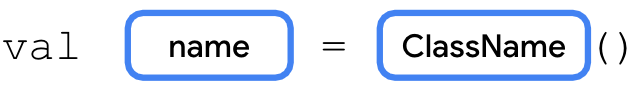

To use an object, you create the object and assign it to a variable, similar to how you define a variable. You use the

valkeyword to create an immutable variable and thevarkeyword for a mutable variable. Thevalorvarkeyword is followed by the name of the variable, then an=assignment operator, then the instantiation of the class object. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Note

When you define the variable with the

valkeyword to reference the object, the variable itself is read-only, but the class object remains mutable. This means that you can’t reassign another object to the variable, but you can change the object’s state when you update its properties’ values.Example:

fun main() { val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() }

Define class methods¶

Actions that the class can perform are defined as functions in the class. For example, imagine that you own a smart device, a smart TV, or a smart light, which you can switch on and off with your mobile phone. The smart device is translated to the

SmartDeviceclass in programming, and the action to switch it on and off is represented by theturnOn()andturnOff()functions, which enable the on and off behavior.The syntax to define a function in a class is identical to what you learned before. The only difference is that the function is placed in the class body. When you define a function in the class body, it’s referred to as a member function or a method, and it represents the behavior of the class. For the rest of this codelab, functions are referred to as methods whenever they appear in the body of a class.

Example:

class SmartDevice { fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } }

So far, you defined a class that serves as a blueprint for a smart device, created an instance of the class, and assigned the instance to a variable. Now you use the

SmartDeviceclass’s methods to turn the device on and off.The call to a method in a class is similar to how you called other functions from the

main()function in the previous codelab. For example, if you need to call theturnOff()method from theturnOn()method, you can write something similar to this code snippet:class SmartDevice { fun turnOn() { // A valid use case to call the turnOff() method could be to turn off the TV when available power doesn't meet the requirement. turnOff() ... } ... }

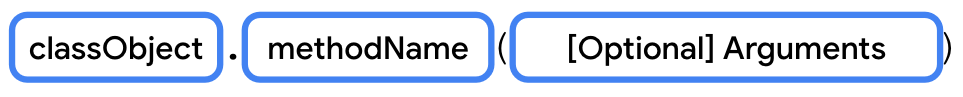

To call a class method outside of the class, start with the class object followed by the

.operator, the name of the function, and a set of parentheses. If applicable, the parentheses contain arguments required by the method. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Example:

fun main() { val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() smartTvDevice.turnOn() smartTvDevice.turnOff() }

Define class properties¶

In Unit 1, you learned about variables, which are containers for single pieces of data. You learned how to create a read-only variable with the

valkeyword and a mutable variable with thevarkeyword.While methods define the actions that a class can perform, the properties define the class’s characteristics or data attributes. For example, a smart device has these properties:

Name. Name of the device.

Category. Type of smart device, such as entertainment, utility, or cooking.

Device status. Whether the device is on, off, online, or offline. The device is considered online when it’s connected to the internet. Otherwise, it’s considered offline.

Properties are basically variables that are defined in the class body instead of the function body. This means that the syntax to define properties and variables are identical. You define an immutable property with the

valkeyword and a mutable property with thevarkeyword.Example:

class SmartDevice { val name = "Android TV" val category = "Entertainment" var deviceStatus = "online" fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } } fun main() { val smartTvDevice = SmartDevice() println("Device name is: ${smartTvDevice.name}") smartTvDevice.turnOn() smartTvDevice.turnOff() }

Properties can do more than a variable can. For example, imagine that you create a class structure to represent a smart TV. One of the common actions that you perform is increase and decrease the volume. To represent this action in programming, you can create a property named

speakerVolume, which holds the current volume level set on the TV speaker, but there’s a range in which the value for volume resides. The minimum volume one can set is 0, while the maximum is 100.To ensure that the

speakerVolumeproperty never exceeds 100 or falls below 0, you can write a setter function. When you update the value of the property, you need to check whether the value is in the range of 0 to 100.As another example, imagine that there’s a requirement to ensure that the name is always in uppercase. You can implement a getter function to convert the

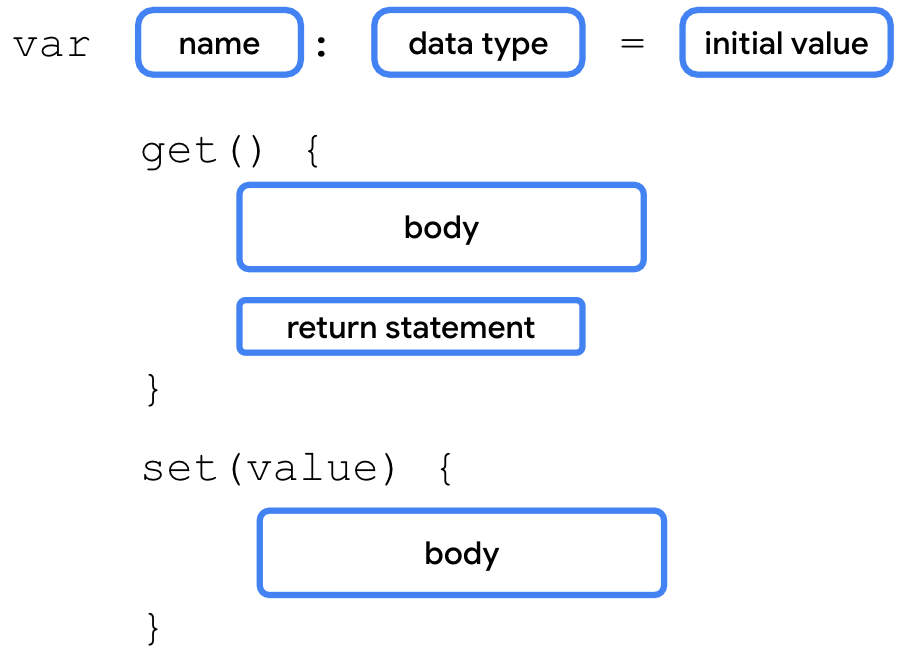

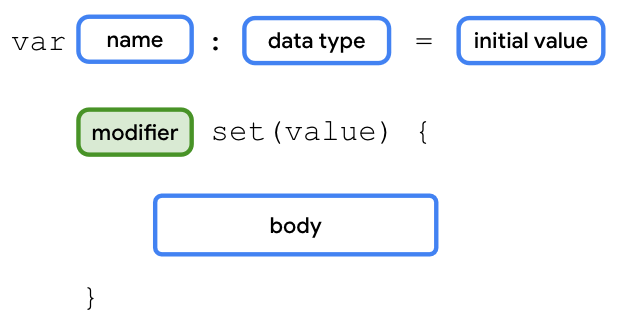

nameproperty to uppercase.Before going deeper into how to implement these properties, you need to understand the full syntax to declare them. The full syntax to define a mutable property starts with the variable definition followed by the optional

get()andset()functions. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

When you don’t define the getter and setter function for a property, the Kotlin compiler internally creates the functions. For example, if you use the

varkeyword to define aspeakerVolumeproperty and assign it a2value, the compiler autogenerates the getter and setter functions as you can see in this code snippet:

var speakerVolume = 2

get() = field

set(value) {

field = value

}

You won’t see these lines in your code because they’re added by the compiler in the background.

The full syntax for an immutable property has two differences:

It starts with the

valkeyword.The variables of

valtype are read-only variables, so they don’t haveset()functions.

Kotlin properties use a backing field to hold a value in memory. A backing field is basically a class variable defined internally in the properties. A backing field is scoped to a property, which means that you can only access it through the

get()orset()property functions.To read the property value in the

get()function or update the value in theset()function, you need to use the property’s backing field. It’s autogenerated by the Kotlin compiler and referenced with afieldidentifier.For example, when you want to update the property’s value in the

set()function, you use theset()function’s parameter, which is referred to as the value parameter, and assign it to the field variable as you can see in this code snippet:var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { field = value }

Warning

Don’t use the property name to get or set a value. For example, in the

set()function, if you try to assign the value parameter to thespeakerVolumeproperty itself, the code enters an endless loop because the Kotlin runtime tries to update the value for thespeakerVolumeproperty, which triggers a call to the setter function repeatedly.For example, to ensure that the value assigned to the

speakerVolumeproperty is in the range of 0 to 100, you could implement the setter function as you can see in this code snippet:var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } }

The

set()functions check whether theIntvalue is in a range of 0 to 100 by using theinkeyword followed by the range0..100. If the value is in the expected range, thefieldvalue is updated. If not, the property’s value remains unchanged.You include this property in a class in the Implement a relationship between classes section of this codelab, so you don’t need to add the setter function to the code now.

Define a constructor¶

The primary purpose of the constructor is to specify how the objects of the class are created. In other words, constructors initialize an object and make the object ready for use. You did this when you instantiated the object. The code inside the constructor executes when the object of the class is instantiated. You can define a constructor with or without parameters.

Default constructor¶

A default constructor is a constructor without parameters. You can define a default constructor as shown in this code snippet:

class SmartDevice constructor() { ... }

Kotlin aims to be concise, so you can remove the

constructorkeyword if there are no annotations or visibility modifiers, which you learn about soon, on the constructor. You can also remove the parentheses if the constructor has no parameters as shown in this code snippet:class SmartDevice { ... }

The Kotlin compiler autogenerates the default constructor. You won’t see the autogenerated default constructor in your code because it’s added by the compiler in the background.

Parameterized constructor¶

In the

SmartDeviceclass, thenameandcategoryproperties are immutable. You need to ensure that all the instances of theSmartDeviceclass initialize thenameandcategoryproperties. With the current implementation, the values for thenameandcategoryproperties are hardcoded. This means that all the smart devices are named with the"Android TV"string and categorized with the"Entertainment"string.To maintain immutability but avoid hardcoded values, use a parameterized constructor to initialize them:

class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" fun turnOn() { println("Smart device is turned on.") } fun turnOff() { println("Smart device is turned off.") } }

The constructor now accepts parameters to set up its properties, so the way to instantiate an object for such a class also changes. You can see the full syntax to instantiate an object in this diagram:

Note

If the class doesn’t have a default constructor and you attempt to instantiate the object without arguments, the compiler reports an error.

Example:

SmartDevice("Android TV", "Entertainment")

Both arguments to the constructor are strings. It’s a bit unclear as to which parameter the value should be assigned. To fix this, similar to how you passed function arguments, you can create a constructor with named arguments as shown in this code snippet:

SmartDevice(name = "Android TV", category = "Entertainment")

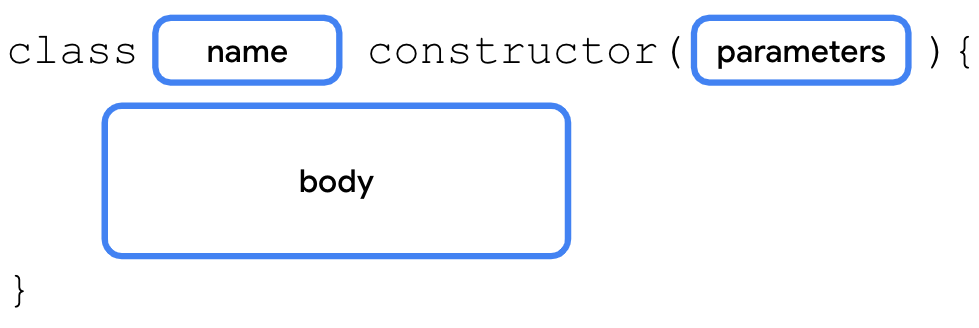

There are two main types of constructors in Kotlin:

Primary constructor. A class can have only one primary constructor, which is defined as part of the class header. A primary constructor can be a default or parameterized constructor. The primary constructor doesn’t have a body. That means that it can’t contain any code.

Secondary constructor. A class can have multiple secondary constructors. You can define the secondary constructor with or without parameters. The secondary constructor can initialize the class and has a body, which can contain initialization logic. If the class has a primary constructor, each secondary constructor needs to initialize the primary constructor.

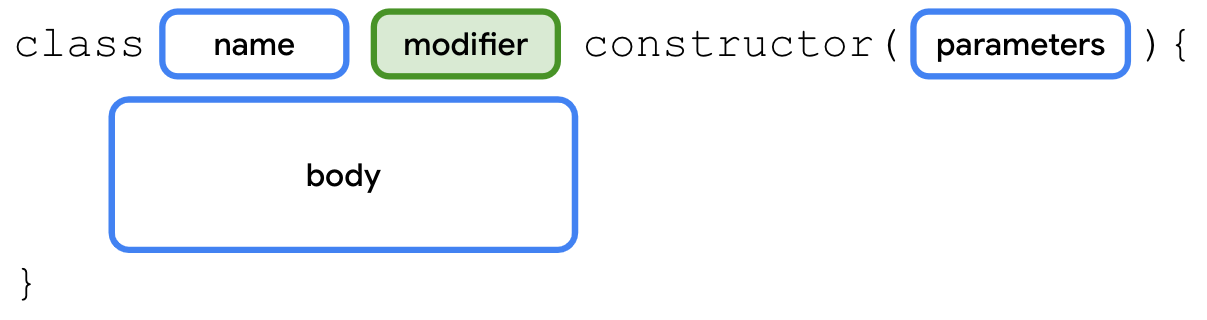

You can use the primary constructor to initialize properties in the class header. The arguments passed to the constructor are assigned to the properties. The syntax to define a primary constructor starts with the class name followed by the

constructorkeyword and a set of parentheses. The parentheses contain the parameters for the primary constructor. If there’s more than one parameter, commas separate the parameter definitions. You can see the full syntax to define a primary constructor in this diagram:

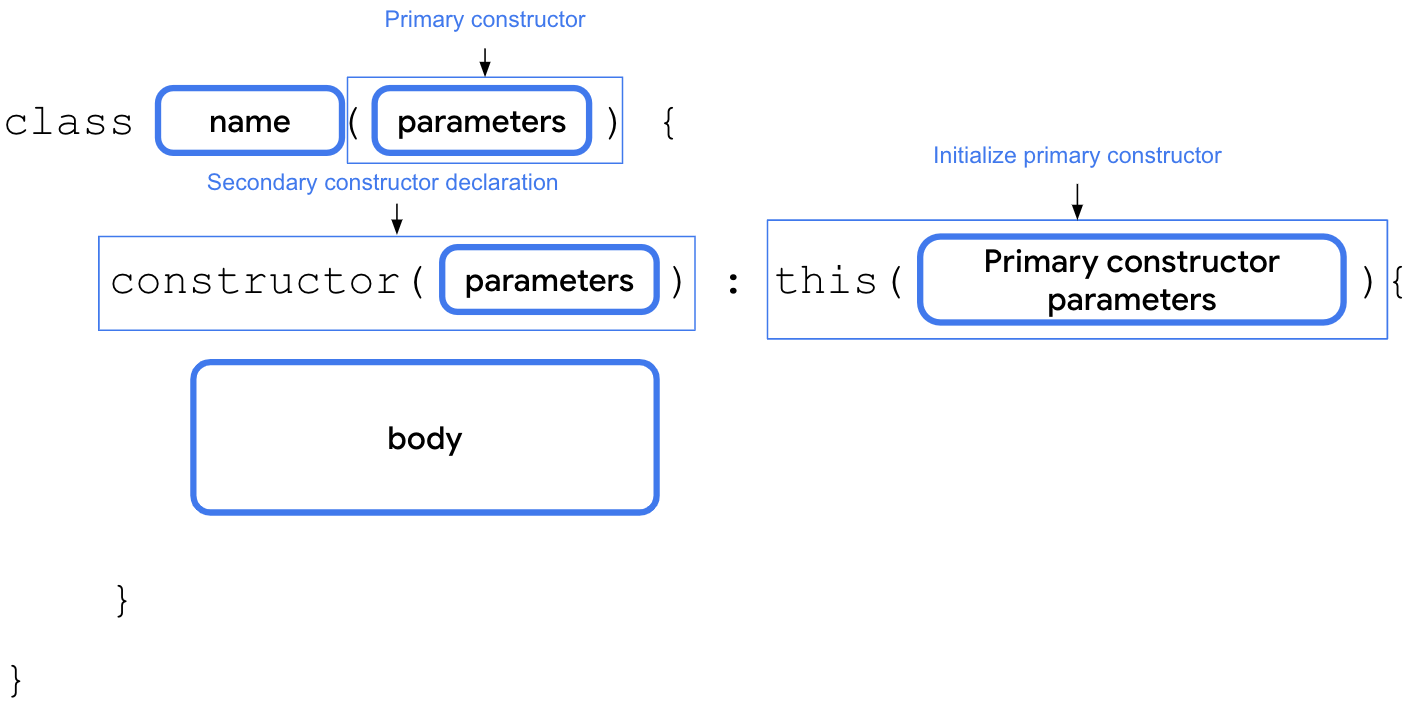

The secondary constructor is enclosed in the body of the class and its syntax includes three parts:

Secondary constructor declaration. The secondary constructor definition starts with the

constructorkeyword followed by parentheses. If applicable, the parentheses contain the parameters required by the secondary constructor.Primary constructor initialization. The initialization starts with a colon followed by the

thiskeyword and a set of parentheses. If applicable, the parentheses contain the parameters required by the primary constructor.Secondary constructor body. Initialization of the primary constructor is followed by a set of curly braces, which contain the secondary constructor’s body.

For example, imagine that you want to integrate an API developed by a smart device provider. The API returns a status code of

Inttype to indicate initial device status. The API returns a0if the device is offline and a1if the device is online. For any other integer value, the status is considered unknown. You can create a secondary constructor in theSmartDeviceclass to convert thisstatusCodeparameter to string representation as you can see in this code snippet:class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" constructor(name: String, category: String, statusCode: Int) : this(name, category) { deviceStatus = when (statusCode) { 0 -> "offline" 1 -> "online" else -> "unknown" } } ... }

Implement a relationship between classes¶

Inheritance lets you build a class upon the characteristics and behavior of another class. It’s a powerful mechanism that helps you write reusable code and establish relationships between classes.

For example, there are many smart devices in the market, such as smart TVs, smart lights, and smart switches. When you represent smart devices in programming, they share some common properties, such as a name, category, and status. They also have common behaviors, such as the ability to turn them on and off.

However, the way to turn on or turn off each smart device is different. For example, to turn on a TV, you might need to turn on the display, and then set up the last known volume level and channel. On the other hand, to turn on a light, you might only need an increase or decrease to the brightness.

Also, each of the smart devices has more functions and actions that they can perform. For example, with a TV, you can adjust the volume and change the channel. With a light, you can adjust the brightness or color.

In short, all smart devices have different features, yet share some common characteristics. You can either duplicate these common characteristics to each of the smart device classes or make the code reusable with inheritance.

To do so, you need to create a

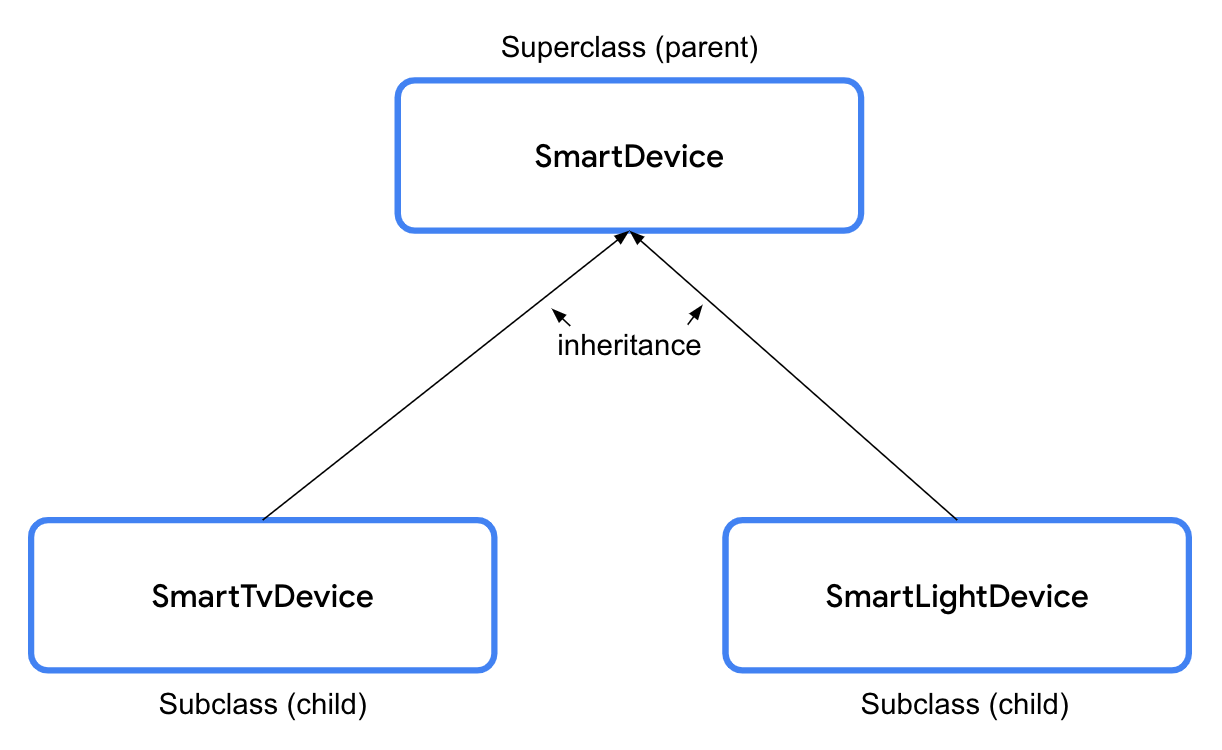

SmartDeviceparent class, and define these common properties and behaviors. Then, you can create child classes, such as theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses, which inherit the properties of the parent class.In programming terms, we say that the

SmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses extend theSmartDeviceparent class. The parent class is also referred to as a superclass and the child class as a subclass. You can see the relationship between them in this diagram:

In Kotlin, all the classes are final by default. Final means that you can’t extend them. To make a class extendable, it is necessary to use the

openkeyword.The

openkeyword informs the compiler that a class is extendable, so that other classes can extend it.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... }

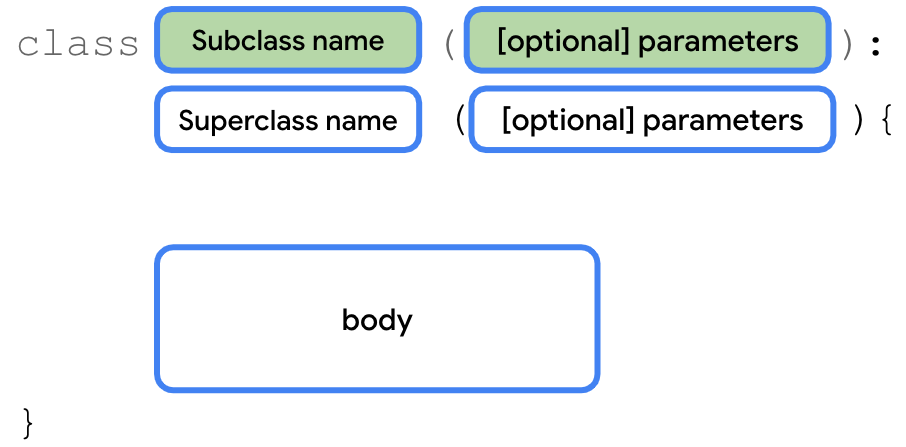

The syntax to create a subclass starts with the creation of the class header as you’ve done so far. The constructor’s closing parenthesis is followed by a space, a colon, another space, the superclass name, and a set of parentheses. If necessary, the parentheses include the parameters required by the superclass constructor. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Example:

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { }

The constructor definition for

SmartTvDevicedoesn’t specify whether the properties are mutable or immutable. This means that thedeviceNameanddeviceCategoryparameters are merely constructor parameters instead of class properties. You won’t be able to use them in the class, but simply pass them to the superclass constructor.The full

SmartTvDeviceclass might look like this:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } }

Sample code for the

SmartLightDeviceclass:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } }

Relationships between classes¶

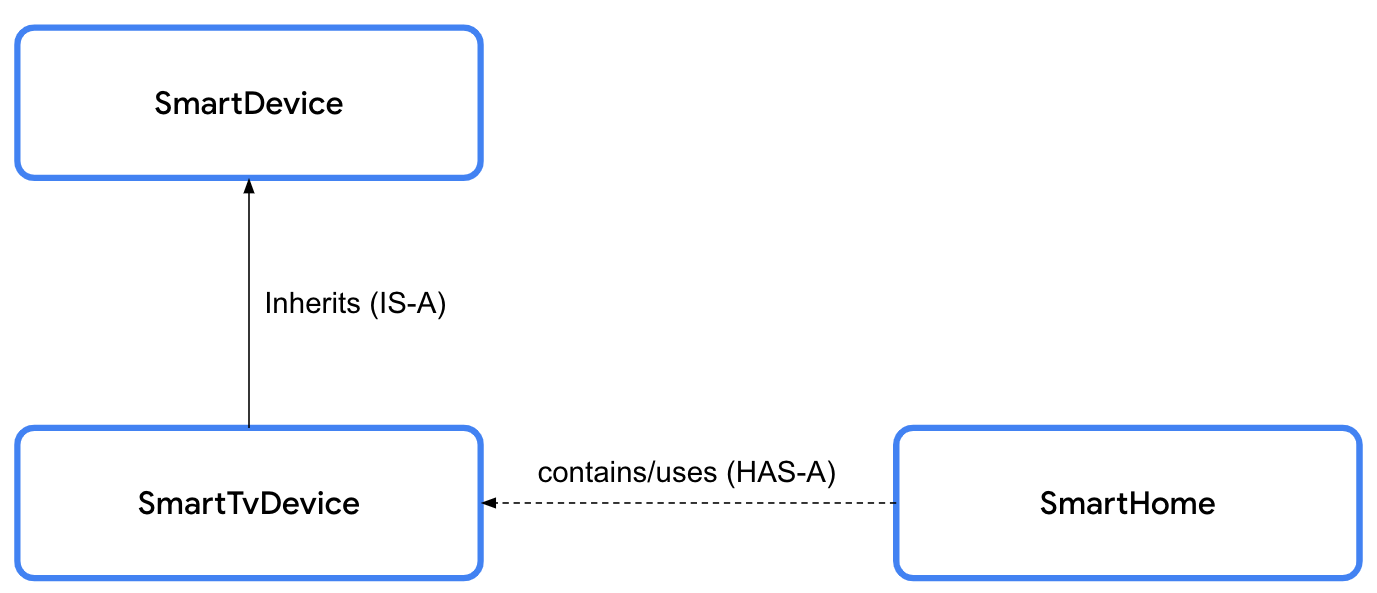

When you use inheritance, you establish a relationship between two classes in something called an IS-A relationship. An object is also an instance of the class from which it inherits. In a HAS-A relationship, an object can own an instance of another class without actually being an instance of that class itself.

IS-A relationships: when you specify an IS-A relationship between the

SmartDevicesuperclass andSmartTvDevicesubclass, it means that whatever theSmartDevicesuperclass can do, theSmartTvDevicesubclass can do. The relationship is unidirectional, so you can say that every smart TV is a smart device, but you can’t say that every smart device is a smart TV. The code representation for an IS-A relationship is shown in this code snippet:// Smart TV IS-A smart device. class SmartTvDevice : SmartDevice() { }

Don’t use inheritance only to achieve code reusability. Before you decide, check whether the two classes are related to each other. If they exhibit some relationship, check whether they really qualify for the IS-A relationship. Ask yourself, “Can I say a subclass is a superclass?”. For example, Android is an operating system.

HAS-A relationships: A HAS-A relationship is another way to specify the relationship between two classes. For example, you will probably use the smart TV in your home. In this case, there’s a relationship between the smart TV and the home. The home contains a smart device or, in other words, the home has a smart device. The HAS-A relationship between two classes is also referred to as composition.

So far, you created a couple of smart devices. Now, you create the

SmartHomeclass, which contains smart devices. TheSmartHomeclass lets you interact with the smart devices. The smart devices are theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDevice.Example:

class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { fun turnOnTv() { smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { smartTvDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseTvVolume() { smartTvDevice.increaseSpeakerVolume() } fun changeTvChannelToNext() { smartTvDevice.nextChannel() } fun turnOnLight() { smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { smartLightDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseLightBrightness() { smartLightDevice.increaseBrightness() } fun turnOffAllDevices() { turnOffTv() turnOffLight() } }

Override superclass methods from subclasses¶

As discussed earlier, even though the turn-on and turn-off functionality is supported by all the smart devices, the way in which they perform the functionality differs. To provide this device-specific behavior, you need to override the

turnOn()andturnOff()methods defined in the superclass. To override means to intercept the action, typically to take manual control, to replace the code in the superclass with other code in the subclass. When you override a method, the method in the subclass interrupts the execution of the method defined in the superclass and provides its own execution.To make a method extendable, use the

openkeyword.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" open fun turnOn() { // function body } open fun turnOff() { // function body } }

The

overridekeyword informs the Kotlin runtime to execute the code enclosed in the method defined in the subclass.Sample code for the

SmartLightDeviceclass:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } }

Sample code for the

SmartTvDeviceclass:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is " + "set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" println("$name turned off") } }

This is an example of polymorphism. When the

turnOn()method of aSmartDevicevariable is called, depending on what the actual value of the variable is, different implementations of theturnOn()method can be executed.

Reuse superclass code in subclasses with the super keyword¶

When you take a close look at the

turnOn()andturnOff()methods, you notice that there’s similarity in how thedeviceStatusvariable is updated whenever the methods are called in theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDevicesubclasses. The code is duplicated. You can reuse the code when you update the status in theSmartDeviceclass.From the subclass, to call the overridden method in the superclass, use the

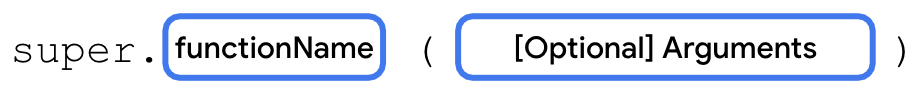

superkeyword.The syntax to call the method from the superclass starts with a

superkeyword followed by the.operator, function name, and a set of parentheses. If applicable, the parentheses include the arguments. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Sample code for the

SmartTvDevice:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is " + "set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() println("$name turned off") } }

Sample code for the

SmartLightDevice:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } }

Override superclass properties from subclasses¶

Similar to methods, you can also override properties.

Example:

open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" open val deviceType = "unknown" ... }

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart TV" ... }

class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart Light" ... }

Visibility modifiers¶

Visibility modifiers play an important role to achieve encapsulation:

In a class, they let you hide your properties and methods from unauthorized access outside the class.

In a package, they let you hide the classes and interfaces from unauthorized access outside the package.

Note

A module is a collection of source files and build settings that let you divide your project into discrete units of functionality. Your project can have one or many modules. You can independently build, test, and debug each module.

A package is like a directory or a folder that groups related classes, whereas a module provides a container for your app’s source code, resource files, and app-level settings. A module can contain multiple packages.

Kotlin provides four visibility modifiers:

public. Default visibility modifier. Makes the declaration accessible everywhere. The properties and methods that you want used outside the class are marked as public.private. Makes the declaration accessible in the same class or source file. There are likely some properties and methods that are only used inside the class, and that you don’t necessarily want other classes to use. These properties and methods can be marked with the private visibility modifier to ensure that another class can’t accidentally access them.protected. Makes the declaration accessible in subclasses. The properties and methods that you want used in the class that defines them and the subclasses are marked with the protected visibility modifier.internal. Makes the declaration accessible in the same module. The internal modifier is similar to private, but you can access internal properties and methods from outside the class as long as it’s being accessed in the same module.

When you define a class, it’s publicly visible and can be accessed by any package that imports it, which means that it’s public by default unless you specify a visibility modifier. Similarly, when you define or declare properties and methods in the class, by default they can be accessed outside the class through the class object. It’s essential to define proper visibility for code, primarily to hide properties and methods that other classes don’t need to access.

For example, consider how a car is made accessible to a driver. The specifics of what parts comprise the car and how the car works internally are hidden by default. The car is intended to be as intuitive to operate as possible. You wouldn’t want a car to be as complex to operate as a commercial aircraft, similar to how you wouldn’t want another developer or your future self to be confused as to what properties and methods of a class are meant to be used.

Visibility modifiers help you surface the relevant parts of the code to other classes in your project and ensure that the implementation can’t be unintentionally used, which makes for code that’s easy to understand and less prone to bugs.

The visibility modifier should be placed before the declaration syntax, while declaring the class, method, or properties as you can see in this diagram:

Visibility modifier for properties¶

The syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a property starts with the

private,protected, orinternalmodifier followed by the syntax that defines a property. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Example:

open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... private var deviceStatus = "online" ... }

You can also set the visibility modifiers to setter functions. The modifier is placed before the set keyword. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

Note

If the visibility modifier for the getter function doesn’t match with the visibility modifier for the property, the compiler reports an error.

For the

SmartDeviceclass, the value of thedeviceStatusproperty should be readable outside of the class through class objects. However, only the class and its children should be able to update or write the value. To implement this requirement, you need to use the protected modifier on theset()function of thedeviceStatusproperty.open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... var deviceStatus = "online" protected set(value) { field = value } ... }

You aren’t performing any actions or checks in the

set()function. You are simply assigning thevalueparameter to thefieldvariable. As you learned before, this is similar to the default implementation for property setters. You can omit the parentheses and body of theset()function in this case:open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... var deviceStatus = "online" protected set ... }

Sample code for the

SmartHomeclass, with a private setter fordeviceTurnOnCount:class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { var deviceTurnOnCount = 0 private set fun turnOnTv() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartTvDevice.turnOff() } ... fun turnOnLight() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartLightDevice.turnOff() } ... }

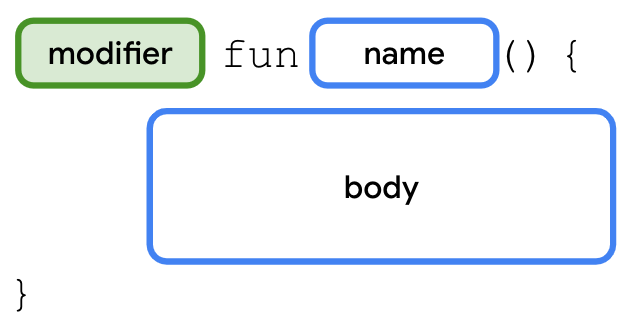

Visibility modifiers for methods¶

The syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a method starts with the

private,protected, orinternalmodifiers followed by the syntax that defines a method. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

For example, you can see how to specify a protected modifier for the nextChannel() method in the SmartTvDevice class in this code snippet:

class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... protected fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } ... }

Visibility modifiers for constructors¶

The syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a constructor is similar to defining the primary constructor with a couple of differences:

The modifier is specified between the class name and the

constructorkeyword.If you need to specify the modifier for the primary constructor, it’s necessary to keep the

constructorkeyword and parentheses even when there aren’t any parameters.

Example:

open class SmartDevice protected constructor (val name: String, val category: String) { ... }

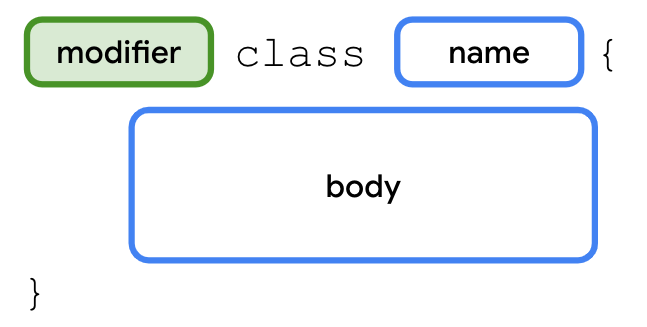

Visibility modifiers for classes¶

The syntax to specify a visibility modifier for a class starts with the

private,protected, orinternalmodifiers followed by the syntax that defines a class. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

For example, you can see how to specify an

internalmodifier for theSmartDeviceclass in this code snippet:internal open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... }

Ideally, you should strive for strict visibility of properties and methods, so declare them with the

privatemodifier as often as possible. If you can’t keep them private, use theprotectedmodifier. If you can’t keep them protected, use theinternalmodifier. If you can’t keep theminternal, use thepublicmodifier.

Specify appropriate visibility modifiers¶

This table helps you determine the appropriate visibility modifiers based on where the property or methods of a class or constructor should be accessible:

Modifier

Accessible in same class

Accessible in subclass

Accessible in same module

Accessible outside module

private

✔

✘

✘

✘

protected

✔

✔

✘

✘

internal

✔

✔

✔

✘

public

✔

✔

✔

✔

In the

SmartTvDevicesubclass, you shouldn’t allow thespeakerVolumeandchannelNumberproperties to be controlled from outside the class. These properties should be controlled only through theincreaseSpeakerVolume()andnextChannel()methods.class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { private var speakerVolume = 2 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } private var channelNumber = 1 set(value) { if (value in 0..200) { field = value } } ... }

Similarly, in the

SmartLightDevicesubclass, thebrightnessLevelproperty should be controlled only through theincreaseLightBrightness()method.class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { ... private var brightnessLevel = 0 set(value) { if (value in 0..100) { field = value } } ... }

Define property delegates¶

You learned in the previous section that properties in Kotlin use a backing field to hold their values in memory. You use the

fieldidentifier to reference it.When you look at the code so far, you can see the duplicated code to check whether the values are within range for the

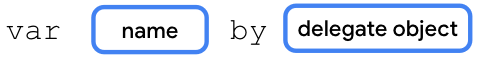

speakerVolume,channelNumber, andbrightnessLevelproperties in theSmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses. You can reuse the range-check code in the setter function with delegates. Instead of using a field, and a getter and setter function to manage the value, the delegate manages it.The syntax to create property delegates starts with the declaration of a variable followed by the

bykeyword, and the delegate object that handles the getter and setter functions for the property. You can see the syntax in this diagram:

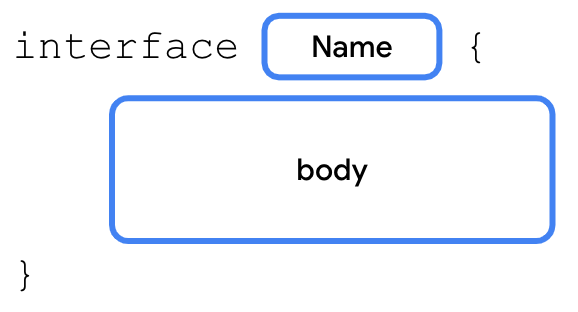

Before you implement the class to which you can delegate the implementation, you need to be familiar with interfaces. An interface is a contract to which classes that implement it need to adhere. It focuses on what to do instead of how to do the action. In short, an interface helps you achieve abstraction.

For example, before you build a house, you inform the architect about what you want. You want a bedroom, kid’s room, living room, kitchen, and a couple of bathrooms. In short, you specify what you want and the architect specifies how to achieve it. You can see the syntax to create an interface in this diagram:

You already learned how to extend a class and override its functionality. With interfaces, the class implements the interface. The class provides implementation details for the methods and properties declared in the interface. You’ll do something similar with the

ReadWritePropertyinterface to create the delegate. You learn more about interfaces in the next unit.To create the delegate class for the

vartype, you need to implement theReadWritePropertyinterface. Similarly, you need to implement theReadOnlyPropertyinterface for thevaltype.Before the

main()function, create aRangeRegulatorclass that implements theReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int>interface:class RangeRegulator() : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { } fun main() { ... }

The angle brackets and the content inside them represent generic types. You learn about them in the next unit.

In the

RangeRegulatorclass’s primary constructor, add aninitialValueparameter, a privateminValueproperty, and a privatemaxValueproperty, all ofInttype:class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { }

In the RangeRegulator class’s body, override the

getValue()andsetValue()methods. These methods act as the properties’ getter and setter functions.class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { } }

Note

KProperty is an interface that represents a declared property and lets you access the metadata on a delegated property. It’s good to have a high-level understanding about what the KProperty is.

On the line before the

SmartDeviceclass, import theReadWritePropertyandKPropertyinterfaces:import kotlin.properties.ReadWriteProperty import kotlin.reflect.KProperty open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { ... } ... class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { } } ...

In the

RangeRegulatorclass, on the line before thegetValue()method, define afieldDataproperty and initialize it withinitialValueparameter. This property acts as the backing field for the variable.class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { } }

In the

getValue()method’s body, return thefieldDataproperty:class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { return fieldData } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { } }

In the

setValue()method’s body, check whether thevalueparameter being assigned is in theminValue..maxValuerange before you assign it to thefieldDataproperty:class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { return fieldData } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { if (value in minValue..maxValue) { fieldData = value } } }

In the

SmartTvDeviceclass, use the delegate class to define thespeakerVolumeandchannelNumberproperties:class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart TV" private var speakerVolume by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 2, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) private var channelNumber by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 1, minValue = 0, maxValue = 200) ... }

In the

SmartLightDeviceclass, use the delegate class to define thebrightnessLevelproperty:class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart Light" private var brightnessLevel by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 0, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) ... }

Test the solution¶

Run this in the Kotlin playground.

import kotlin.properties.ReadWriteProperty import kotlin.reflect.KProperty open class SmartDevice(val name: String, val category: String) { var deviceStatus = "online" protected set open val deviceType = "unknown" open fun turnOn() { deviceStatus = "on" } open fun turnOff() { deviceStatus = "off" } } class SmartTvDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart TV" private var speakerVolume by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 2, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) private var channelNumber by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 1, minValue = 0, maxValue = 200) fun increaseSpeakerVolume() { speakerVolume++ println("Speaker volume increased to $speakerVolume.") } fun nextChannel() { channelNumber++ println("Channel number increased to $channelNumber.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() println( "$name is turned on. Speaker volume is set to $speakerVolume and channel number is " + "set to $channelNumber." ) } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() println("$name turned off") } } class SmartLightDevice(deviceName: String, deviceCategory: String) : SmartDevice(name = deviceName, category = deviceCategory) { override val deviceType = "Smart Light" private var brightnessLevel by RangeRegulator(initialValue = 0, minValue = 0, maxValue = 100) fun increaseBrightness() { brightnessLevel++ println("Brightness increased to $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOn() { super.turnOn() brightnessLevel = 2 println("$name turned on. The brightness level is $brightnessLevel.") } override fun turnOff() { super.turnOff() brightnessLevel = 0 println("Smart Light turned off") } } class SmartHome( val smartTvDevice: SmartTvDevice, val smartLightDevice: SmartLightDevice ) { var deviceTurnOnCount = 0 private set fun turnOnTv() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartTvDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffTv() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartTvDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseTvVolume() { smartTvDevice.increaseSpeakerVolume() } fun changeTvChannelToNext() { smartTvDevice.nextChannel() } fun turnOnLight() { deviceTurnOnCount++ smartLightDevice.turnOn() } fun turnOffLight() { deviceTurnOnCount-- smartLightDevice.turnOff() } fun increaseLightBrightness() { smartLightDevice.increaseBrightness() } fun turnOffAllDevices() { turnOffTv() turnOffLight() } } class RangeRegulator( initialValue: Int, private val minValue: Int, private val maxValue: Int ) : ReadWriteProperty<Any?, Int> { var fieldData = initialValue override fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): Int { return fieldData } override fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: Int) { if (value in minValue..maxValue) { fieldData = value } } } fun main() { var smartDevice: SmartDevice = SmartTvDevice("Android TV", "Entertainment") smartDevice.turnOn() smartDevice = SmartLightDevice("Google Light", "Utility") smartDevice.turnOn() }

Try this challenge¶

In the

SmartDeviceclass, define aprintDeviceInfo()method that prints a"Device name: $name, category: $category, type: $deviceType"string.In the

SmartTvDeviceclass, define adecreaseVolume()method that decreases the volume and apreviousChannel()method that navigates to the previous channel.In the

SmartLightDeviceclass, define adecreaseBrightness()method that decreases the brightness.In the

SmartHomeclass, ensure that all actions can only be performed when each device’sdeviceStatusproperty is set to an"on"string. Also, ensure that thedeviceTurnOnCountproperty is updated correctly.In the

SmartHomeclass, define andecreaseTvVolume(),changeTvChannelToPrevious(),printSmartTvInfo(),printSmartLightInfo(), anddecreaseLightBrightness()method.Call the appropriate methods from the

SmartTvDeviceandSmartLightDeviceclasses in theSmartHomeclass.In the

main()function, call these added methods to test them.

Conclusion¶

There are four main principles of OOP: encapsulation, abstraction, inheritance, and polymorphism.

Classes are defined with the

classkeyword, and contain properties and methods.Properties are similar to variables except properties can have custom getters and setters.

A constructor specifies how to instantiate objects of a class.

You can omit the

constructorkeyword when you define a primary constructor.Inheritance makes it easier to reuse code.

The IS-A relationship refers to inheritance.

The HAS-A relationship refers to composition.

Visibility modifiers play an important role in the achievement of encapsulation.

Kotlin provides four visibility modifiers: the

public,private,protected, andinternalmodifiers.A property delegate lets you reuse the getter and setter code in multiple classes.